VICTORIA COLLEGE - EDUCATING THE ELITE

1902 - 1956

By Samir Raafat

Egyptian Mail, 30 March 1996

edited version in "The Egyptian Bourse" published by Zeitouna 2010

|

|

|

|

|

|

EGY.COM - VICTORIA COLLEGE

|

|

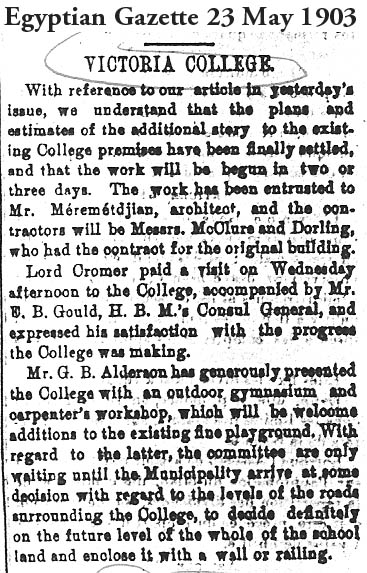

COLONIAL TIMES

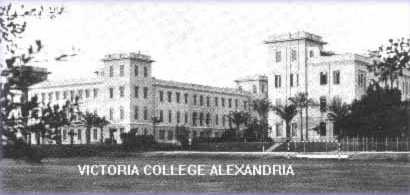

It was a splendid day in Alexandria on the afternoon of 24 May 1906, the birthday anniversary of the late Queen Victoria. It was a very special occasion as royalty, pashas, ministers and Alexandrine notables gathered together at Domaine de Siouf, a coastal retreat several kilometers east of the city. They had come to celebrate the kickoff of what would become the latest symbol of British hegemony in the region: Victoria College. And the empress-queen was again being immortalized in yet another corner of the globe.

Even though Egypt was technically an Ottoman province governed by the sultan's hereditary vassal, Khedive Abbas Hilmi II, Britain had in fact taken over the reigns of power in September 1882 when it launched its military occupation, which was to last for the next seven decades. The country's real ruler in 1906 was one of Britain's greatest imperialists, the first Earl of Cromer formerly known to Egyptians as Sir Evelyn Baring of Barings Bros. fame.

His presence at this landmark solemnization outside Alexandria added to the magic and excitement of the moment. Himself there in the flesh, no one else dared not attend-- khedivial family included. Few suspected that all along Cromer had been against advanced education in Egypt. But "Al Lord" believed that even a little learning was a dangerous thing, especially if the beneficiaries were colonized people. (Who knows, one day they may want to rid themselves of their mentors!) Nevertheless, he must have found some comfort in knowing that British hands would rock the cradle.

Speeches were the order of the day. On behalf of the Muslim community, the Arabic Master, Sheik Mohammed Hamed, spoke in Arabic, while E.B. Gould, the British consul in Alexandria, made his statement in English. Also speaking from the dais were Lord Cromer and Baron Jacques Levi de Menashe. A leading Alexandrine figure, Menashe represented both the city's Austro-Hungarian clique and its powerful Jewish community. Together on the school's executive committee, the British lord and the Jewish baron epitomized the powerful Anglo-Jewish alliance that catalyzed the modernization of Egypt--the symbiotic relationship of the colonizer and the favored minority.

Cromer and Menashe referred in their speeches to the state of education in Egypt, which, save for the religious missions run by Jesuits and other Catholic orders, was deemed inadequate. Native schools, it was understood, could not substitute for a modern European edification. In the meantime, young men wanting to pursue advanced English education had limited choices: either attend the non-progressive religious schools, or travel to England. Now, with the creation of Victoria College, an English public school education was at last within easy reach in the Near East.

While 24 May marked the groundbreaking ceremony of the new Victoria College, the school was in fact into its fourth year. Thanks to public subscription among Alexandria's wealthier British and Jewish residents the original school was inaugurated by Cromer on 1 November 1902, immediately after a serious cholera epidemic that caused a one-month delay.

The school then operated out of modest quarters located in the Mazarita (corrupted from the word [Monsieur] Lazareth) district of Alexandria, overlooking the Eastern Harbor. The land on which the original school was built had been a gift from George Beeton Alderson, who purchased it at a discount from the Egyptian State paying LE 1500. The school's founders quickly resolved to change the original name, "British School," to "Victoria College."

Sir Charles Cookson, George Alderson, Canon Davis, Joseph Aghion, Clement Bohor and Baron Menashe agreed the new name had a better ring to it and would be more conducive to fund raising both in Alexandria and England.

The school's executive committee was made up of leading Alexandrines that invariably meant a mixture of Europeans and Levantine Jews, plus the city's senior civil servants most of whom were British.

The first president of the executive committee was Sir Charles Cookson, British consul general in Alexandria. When he died before the completion of the new Victoria College he was automatically replaced by E.B. Gould.

By agreement, the chief British representative (pro-consul, later high commissioner and ambassador) to Egypt, the consul general in Alexandria and the president of the British Chamber of Commerce of Egypt were the school's ex-officio trustees.

One of Alexandria's noted Anglo-Egyptians, Charles R. Lias (a graduate of Marlborough College and King's College, Cambridge) became Victoria College's first headmaster, receiving 500 pounds per annum. If in 1902-3 there were only 45 students enrolled, by 1906 they had increased more than threefold to 186. They included 13 nationalities broken down into three religious groups; there were 80 Christians, 67 Jews and 39 Muslims, mirroring the city's upper-class mosaic. The school's motto was "Cuncti gens una sumus," meaning "joined together as one people.

With high demand for enrollment, it was evident that newer and bigger premises were needed, even though there were already plans to enlarge the old ones. Even before the move, an entire new floor was added courtesy of contractor Kevork Meramedjian under the supervision of McClure & Dorling, who had built the original building conforming to architect H. Favarger original design.

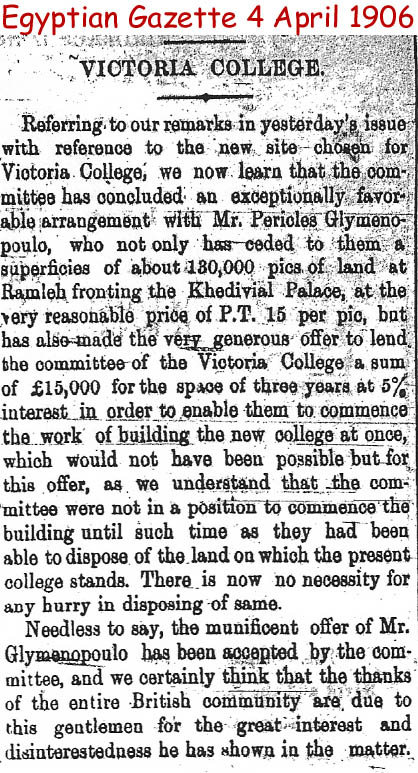

The new 17-acre grounds at Domaine de Siouf were mostly bought with private donations; in addition, Khedive [ABBAS HILMI II?] donated part of the land. With space no longer a major consideration, the new school was conceived to accommodate upwards of 500 students.

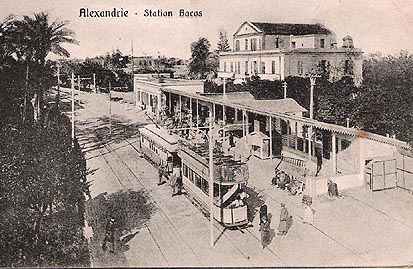

The only other edifice worth mentioning in the IMMEDIATE area was Al Saray Al Hazina (Palace of Sorrows), which belonged to the Khediva-Mother. For a short time, the hilltop saray was the khedive's temporary residence while he supervised the construction of his seaside palais de chasse, Montaza Palace. In time for the groundbreaking ceremony, the Bacos & Schutz tramlines which had heretofore ended at San Stefano, were extended further east. The new terminus was situated midway between Saray al Hazina station and the school's new grounds, not too far from the Alexandria-Abou Kir-Rosetta Railway.

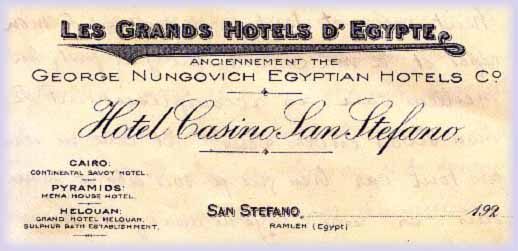

Also not far from the new Victoria College was another famous landmark, the Ramleh Casino. This fin-de-siecle monument constructed in 1886-7 was imagined and conceived by Boghos Nubar Pasha, son of the Armenian statesman-administrator Nubar Nubarian. Having studied at the école Central in Paris, Boghos was infatuated with the famous casinos and seaside resorts dotting the Franco-Belgian coast between the fashionable towns of Deauville and Ostende. The result was Ramleh-Les-Bains's majestic San Stefano Hotel & Casino.

Architecture and ambiance were not the only European ingredients that made it across the Mediterranean. On 24 May 1906, the Casino's menu featured a range of continental dishes:

RAMLEH LES BAINS

> The casino, the Saray and the new English public school could be reached via Strada Rossa (afterwards Fouad Avenue, now Tarik Al Horeya). Ramleh's main artery ran a west-east axis from Alexandria's Rue Porte de Rosette through various residential townships until it finished at Siouf. Strada Rossa, or "Red Street," was so named because it was covered with reddish potsherds from the ruins of Roman Alexandria. The Corniche was still unheard of in those days.

What did Victoria's non-boarding students see as they traveled to school by car, tram or horse 'n' buggy? "Ramleh" comes from the Arabic word for sands, and that's exactly how Alexandria's cosmopolitan set perceived this narrow, sparsely Bedouin-inhabited bayside stretch sandwiched between the Mediterranean to the north and salty marshes to the south. Ramleh's convenient location and the steady northerly winds sweeping across its rows of palm-decked dunes had a seductive effect on Alexandria's taipans and compradores, and it was thanks to a gathering of these far-sighted entrepreneurs that in 1860 the decision was made to link Ramleh with Alexandria by rail.

Soon after, Constantin Zervudachi, E. Cornish, Constantine and P. Salvagos, Charles Royle, Dr. Varenhorst Pasha and A. Caillard founded the Alexandria & Ramleh Railway Co., with a concession of 70 years. Just into the twentieth century, the company replaced the steam engine with electrification.

By summer 1890, a regular train service ran between Alexandria and San Stefano, peaking at 24 trains per day. On Sundays, 5048 chairs belonging to the seaside Casino were barely sufficient. And the waiting list to join the genteel San Stefano Club was twice as long as its 425 membership. As Ramleh became increasingly accessible, the Casino's owners decided to act in response to these welcome statistics, and in 1893 Nicolas Sabagh, the casino's Syrian secretary, commissioned architect Leon Stienon of the Alexandria Municipality (and part time Dutch consul-general) to add a new a western wing.

The enlarged hotel was run by Alexandria's maverick hotelier Luigi Steinschneider, who later became the director of Zamalek's Gezira Palace Hotel, when it was still managed by the Egyptian branch of the Wagons-Lits.

Meanwhile, back in Ramleh, it was another European, Jules Castravelli, who ran the important tramway station of San Stefano. His opposite number at the Alexandria terminal situated at Rue al-Chatby (also known as Ramleh Station) was a Signor Marsiglio.

By 1910, the Ramleh's various suburbs had matured into small townships. Each had a distinct flavor and its own set of notables, their houses surrounded by vast gardens. With the use of cisterns for storing pumped water from the Mahmoudia fresh-water canal south of Bulkley, the once-empty sands flowered. These topographical transformations were amply visible from the trams' windows. Alexandrines marveled at the horticultural wonders created by their city's business elite. Equally breathtaking were the grand homes belonging to Alexandria's colonial merchants, moneylenders, and its cotton, tobacco and timber barons.

At Bacos, the gardens of Tousson Pasha, Camilleri and Sinadino-Ralli exuded year-round colors and fragrances. It was the same at Seffer, with the garden-plantations of Prince Hussein Kamel, Contandinidis and Tachau. Passing through Zizinia, tram riders gawked at the palatial home of Count Macandro Zizinia.

In Schutz and beyond, the villas of Zervudachi, Zancarol, Dikeos, Sursock and Cattaui dominated the scene. In a time when drip irrigation was as remote as Mars, the springtime horticulture show at Casino San Stefano was kept alive for over half a century. Aluminum and concrete, too, were still unknown, but both would one day, trample Ramleh's greenery with devastating effects, as though the entire area had been sprayed with Napalm or Agent Orange.

Along the scenic tramway, it was obvious that Alexandria's diverse foreign communities had already staked their claims in Ramleh. Villa Allen, Villa Hicks, Villa Peak, Villa Kingham, (Sir George) Alderson Castle, Sidney Carver House and Moss Hill were obviously British. Villa Augusto Luzatto and Villa Emanuel Stross belonged to nationals from quaint and unpronounceable Austro-Hungarian dominions. Meanwhile, Villa Princess and Villa Reale belonged to minor nobility from Ruritania-like principalities and wealthy traders who aspired to a papal coat of arms, like the Zoghebs and the Debanes.

Other Levantines include the owners of Villa Karam (ex-Tamvaco), Villa Marelli, Palais Joseph Pharaon, Villa Spanopoulo, Villa Maestracci and Villa Benachi. There was also Villa Hermitage, belonging to Monsieur Laurens, the French tobacco dealer. Like Mr. Fleming, he had an entire garden district named after him. Another district was named after Perikles Glymonopoulo, director of the Alexandria and Ramleh Railway Company.

Mr. Glymonopoulo was also the administrator of the Egyptian Trust and Investment Company that owned large landholdings in the district of Ramleh. He was among the first to realize that it was evident additional tram line branches would be required to service the sprawling new suburbs east of Alexandria.

"What's this name?" Ilya Perrera exclaimed, pointing his small hand in the direction of a house not too far from the tram tracks. "It sure doesn't sound like they're from these parts," replied his older school chum Alexander Ruppa. On their way to Victoria, their curiosity was piqued by a sign on a garden gate that said "Villa Abaza".

On ordinary school days, one would run into all kinds of rowdy students, identifiable by their different uniforms. At each station some got off. At Bacos was L'Ecole des Freres, and at Fleming was the famous Notre Dame de Sion.

Last to alight were Perrera and Ruppa along with their schoolmates, Fianni, Nadler, Levy, Coroneos and Vitsentzos. Like at any public school in England, they sported flannel caps, gray shorts and striped school ties--probably purchased at one of Alexandria's two famous Welsh-owned department stores, Davies Bryan and Robert Hughes outfitters [Outfitters]. On their blazers, Perrera and Ruppa proudly wore the VC badge. This was sometimes flanked with golden leaves, denoting the bearer as a monitor or a prefect. The head boy had the most leaves, with the initials "HB" appended.

As Egypt's first generation of future "Old Boys" arrived at their destination, the Ramleh tramway reached the end of the line.

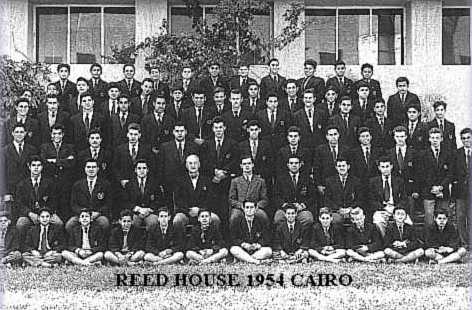

Physically, Victoria College was a reproduction of an English public school, with its own collection of "houses." First these had imperialistic sounding names like Cromer, Kitchener and Lloyd, which were supplemented later with Reed, Barker, Frobisher and Drake. There were housemasters and captains, prefects and monitors. Cruelties like fagging and caning were de rigeur. Many may remember Mr. Scovil's precious collection of whips kept in a French-style glass-door cabinet.

Religious influences were not admitted at Victoria College, especially any that might block the path of educational progress and ultimately work against British hegemony. This formative British institution was expected, unofficially, to mold future generations and convert young minds into pro-British elements from amongst whose ranks would rise regional leaders and senior administrators. Given that objective, it was not a bad course to bring bit of Cheltenham and Harrow to Domaine de Siouf. Oxford and Cambridge could later do the rest.

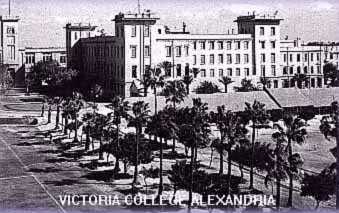

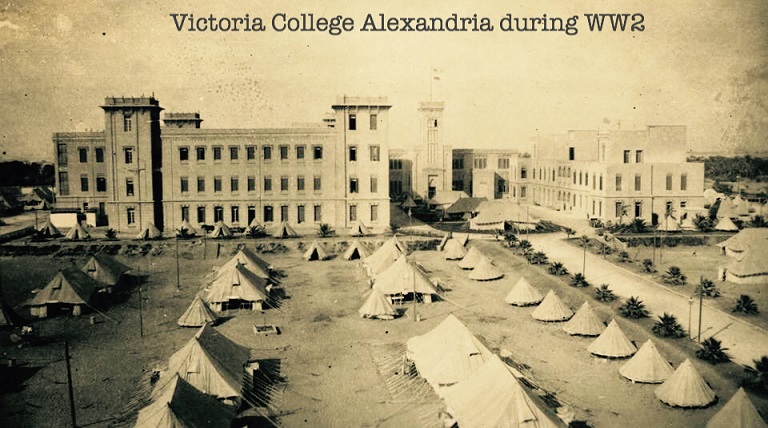

Lord Cromer's successor, Sir Eldon Gorst, would ordinarily have inaugurated the school's new premises, designed and built by Henry Gorra Bey. The honor, however, went to Queen Victoria's son Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught. During his extended trip to Egypt, Prince Arthur, together with the duchess and their daughter Princess Patricia, traveled by special train from Cairo to Alexandria on 27 March. With only a 15-minute delay the royal cortege drove from Sidi Gaber to Domaine de Siouf. At the school's entrance the Duke's Own Rifle Brigade stood guard, and the regimental band marched up and down the school's main hall, entertaining 1000 privileged guests as they waited for the royal guest of honor.

The strains of "God save the King" were heard at 4:20pm, signaling that their royal highnesses had arrived. Received by Consul E.B. Gould, the royals were presented to headmaster Charles Lias and to the rest of the school's committee.

In his address the duke thanked the headmaster and the committee for their valiant efforts. He then shook hands with head boy Michael Antonious, and greeted Cromer scholar Emil Kordahi. At this point, Prince Arthur handed the Oxford and Cambridge Joint Board certificates to Sixth Form honor students Michael and George Antonious, E. Harle, S. Shoukri, Emil Kordahi, M. Morsi, A. Messiqua, Sydney Naggiar, S. Mizrahi, Alexander Ruppa and Curiel. As tradition required, the head boy proceeded to call for three cheers for the royal visitors.

Before they left, the Connaughts signed their names on the commemorative stone tablet in blue chalk, which would later be carved up in a facsimile of their writing. Three years after laying the inaugural stone, the school's new premises had thus been officially opened.

Yet, in fact, the school had already moved to Siouf during October of the previous year, with the interim months acting as a dry run to make sure everything worked. Last minute hitches such as the collapse of one of the building's towers (from which British artist Rhona Haszard would take a fatal fall in 1931 while living on the premises with her husband Leslie Greener who taught art and French) had caused construction delays and necessitated a major outlay of funds. The vacated Mazarita premises, meanwhile, was re-purchased by Charles Alderson at LE 100,000, henceforth to be known as Immeuble Alderson. Its first post Victoria College occupant was another school, the Lycé Francais, followed by the Egyptian Survey Department.

As they visited the school's new premises, parents could see for themselves their children's health and welfare was amply provided for. Sanitary facilities had been entrusted to Messrs. George Jennings Ltd. and installed under the personal supervision of John Dixon, who used similar equipment at the British government houses in Gezira-Zamalek. As for the drainage system, this was installed by no less than the eminent drainage engineer Carkeet James, who had introduced Cairo's first public sewage system.

The well-ventilated classrooms were designed to hold 22 students each--none of that overcrowding that had characterized the old school and its dormitories. Parents were also treated to a tour of the laboratories. Modern scientific equipment were proudly exhibited by science master Mr. Aubrey formerly of Coventry. (His domain would be enhanced two years later when Sir (Dr.) Marc Armand Ruffer offered the school a whole new set of fittings and equipment.

Then Mr. Curnow showed his art rooms, and Mr. Parkhurst the school's library. Next stop, the dining room seated up to 500 students at a time. Also to be admired were the school's gymnasium and fencing rooms, next to the Masters' Commons. Outdoor sports were regarded as an important source of discipline and character formation--hence football, hockey and cricket, in which both masters and students took part.

When the Bishop of London visited the school in March 1912, he was delighted to note that the cult of the public school had entrenched itself in Egypt, and elaborated on how the public school spirit was one of the best traditions of the English nation. "A British Field-Marshal does not carry his baton more proudly than he wears his school tie," he declared. And, the Bishop assured concerned parents, since three of the elements that make up a good independent liberal school were in place at Victoria--good masters, good buildings and good playgrounds--they need no longer worry about sending their children to Eton, Rugby Winchester or Harrow.

But who were the lucky boys who made it into Victoria College? According to the school's original 1902 regulations, no boy would be admitted over 14 or under seven. A certificate of good character was required of boys who had been to other schools. Boys over nine were expected to read Arabic, English or French and to have an elementary knowledge of arithmetic. Courses of instruction included Arabic, English, French, history, geography, mathematics, science, drawing and physical education. Religious instruction was not obligatory, and given only by arrangement to those pupils whose parents expressed a wish to that effect.

School hours were from 8am to 5pm with some intervals. There was no work on Sundays, while Saturday was a half-holiday. The school year was divided into three terms Michaelmas, Easter and Summer of three months each. Fees were payable in advance and due the first day of each term; parents were required to give the usual term's notice of withdrawal. The fees posted in 1908 they were as follows:

Boarders under 10 LE1.65 per month - Boarders over 10 LE1.95 Dayboys below 10 LE0.75 - Dayboys above 10 LE0.90 The dayboy fees included the midday meal.

The first alliance of Old Victorians was formed in May 1912. It consisted of 30 former students. "The Old Victorian Association" included Albert Nimr, Kamal Abaza, G. Valassopoulo, W. Perrera, L. Ovadia, R. Landauer, J. Barda, H.W. Hanna, A. Nahas, A. Messiqua and George Antonious.

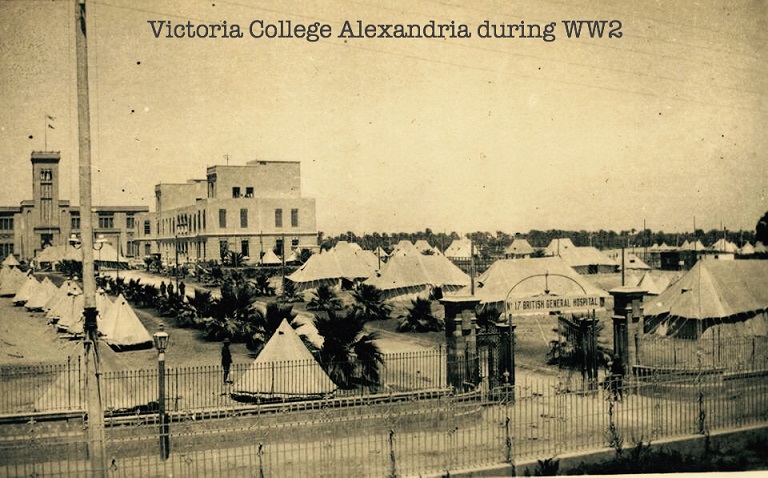

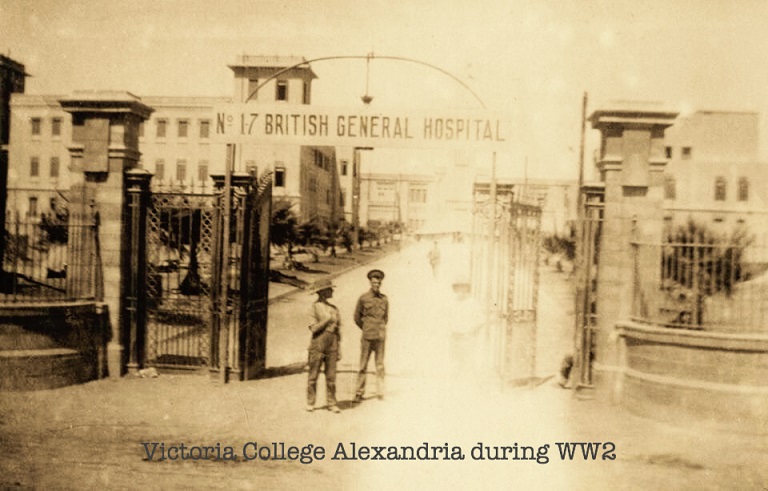

Two years later, the association's activities were suddenly suspended when Victoria College was commandeered by the British High Command. World War I was underway, and Victoria College was unexpectedly transformed into the headquarters of the Corps Expeditionaire d'Orient under the command of General d'Amade. A few months later it became home to the 17th British General (military) Hospital. [British army's 17th General Hospital unit]

Fighting in the Dardanelles took a heavy toll, and soon thousands of casualties were shipped back to Egypt many of whom passed through Victoria College's gates. The school camped at Mazarita for close to five years, returning from in the old premises in 1919. Ralph William Gordon Reed, formerly of Wadham College, Oxford and then a teacher of English at Victoria College, was the school's new headmaster.

By 1920 it was common practice for students to be involved in three extra-curricular activities: Theatricals in December, Sports Day in May and Prize Day on the eve of the long summer break. Another event, not so much the concern of the students as of Egypt's British administrators and the country's native politicians, was the annual Victoria College Speech Day. For three decades this event served as an unofficial forum for reviewing and vetting Britain's policy in Egypt.

In the absence of an Egyptian parliament or a speech from the throne, Victoria College's Speech Day was likened to a "state of the nation" address. The next morning's headlines would invariably be entirely dedicated to this event, with proclamations like "Epoch-making speech by the high commissioner at Alexandria" or "Prime minister on fostering Anglo-Egyptian goodwill".

Between 1902 and 1921 the country changed from an Ottoman province into a British protectorate before becoming a constitutional monarchy in 1922 when Britain unilaterally announced Egypt's independence. Likewise, the nominal ruler was in turn called "Khedive," then "Sultan," then "King." Throughout these changes, Speech Day remained a carefully orchestrated display of imperialist pomp and ceremony marking the pre-eminence of British rule in the region. Each year, the British pro-consul--upgraded to high commissioner after 1914--arrived at Victoria College in his ceremonious cortege escorted by a mounted guard of honor. At the main building, the pro-consul or high commissioner was welcomed by the headmaster and representatives of Egypt's ruling class, including one or two princes of the court.

The Egyptian prime minister and members of his cabinet were also there to greet the Lord, whether Kitchener, Wingate or Allenby. Next in the receiving line were the school's board of trustees and notables from Cairo and Alexandria. In the Main Hall, at a distance, sat the housemasters, the prefects and the older students. Tradition required that Speech Day ceremonies end with a recitation by the head boy and the customary rallying call for three cheers.

When a national parliament convened for the first time in 1924, Speech Day gradually lost some its imperialist aura. The civilized transfer of power had begun. Yet, unhindered by these changes, Victoria College continued its Anglicizing mission. As far as protocol and ceremonial precedence were concerned, a new pecking order was simply put in place. Henceforth, it was the Egyptian prime minister who was welcomed at the school's main building by both the headmaster and the British high commissioner.

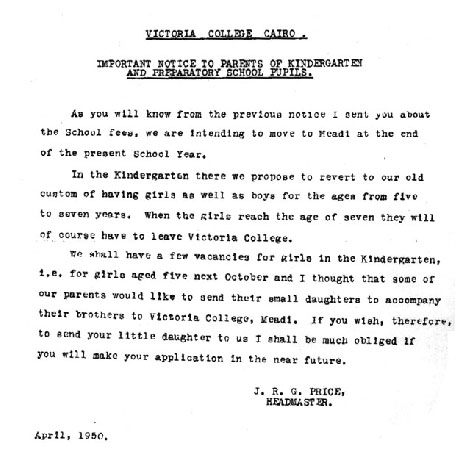

Another departure from tradition was the creation in 1927 of a kindergarten for boys from five to seven years of age. The children were looked after by a fully trained English "Froeble mistress."

At about this period discussions started for the opening of an English Girls' school along the same lines as Victoria College. One would eventually open at Villa Zervudachi, Zizinia in 1935. By that time the annual Cromer Scholarship, awarded over the previous 20 years to Victoria College graduates by the examiners of the Oxford and Cambridge Board, had been given to seven Syrians, five Jews, three Greeks, three Brits, two Armenians and one Egyptian.

In 1929, Prime Minister Mohammed Mahmoud Pasha broke with tradition and made his Speech Day address in English. In previous years, Egyptian guest speakers had used French, not surprising in view of their predominantly Gallic education. With the precedent set by Mahmoud Pasha, the cultural Anglicization of Egypt was confirmed.

Mahmoud Pasha remarked that Old Victorians were absent from Balliol College, Oxford, from where he himself had graduated, and tended to go instead to Cambridge. Seated next to him on the dais was Lord Lloyd George, the British high commissioner, a graduate of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge. The pasha's subtle comment served to remind the lord that as Oxbridge graduates, they had come here to speak as equal partners.

In January 1934, a Victoria College graduate was elected to an Open Entrance Scholarship at Oxbridge for the first time. To the school's credit, former head boy Charles Elias Issawi won a demyship in Modern History at Magdalene College, Oxford. Issawi, later a well-known historian, had in his school days edited The Victorian (created by Mr. Reed in December 1912), and won the Smouha and Cromer scholarships (1929 and 1931 respectively). The latter was considered the highest academic achievement attainable at Victoria College.

Other in-house Victoria College scholarships included over the years those named after (Oswald) Finney, (Col. E.T.) Peel, (Edwin) Goar, (Youssef) Smouha, (Constantin) Choremi, (O.) Matossian, (Antonio (Fabri), (J.) Casulli, Swinglehurst, (Amin) Yehya, N. Sursock and (Edouard) Karam. All had been generous patrons and fundraisers. Victoria College was beneficiary of handsome donations from former students. Whereas the scout pavilion and a piece of land were donated by Edwin Goar, the Wolf Cubs Hall was a gift from Kamel Wassef. Similarly, a complete set of the Annual Registry from 1758 to 1913 was donated to the school's library by Vitalis Sidi, father of student Alfred Vitalis.

From the formation of the First Alexandrian British Scouts of Egypt by D. E. Preece in 1912, Victoria College never wanted for either a superb Cub pack or an active Boy Scout troop. Some will remember how after World War II, during "Skip" Young's tenure as Scout Master, the school acquired an old British lifeboat. Sailing classes took place mostly along the coast from Abou Kir to Agami. In 1951, the scouts attended the Scout Jamboree in Bad Ischl, Austria before traveling by rail to the UK to visit the Scout headquarters at Gilwell Park. Lord Baden Powell, the Scouts' founder, knew Victoria College well and had been one of its guest speakers.

In 1934 there were 350 students at Victoria College, and the alumni counted just as many Old Boys who had penetrated all kinds of professions. Mohammed Farghali was in cotton and textiles, Mahmoud Abaza in medicine, Mahmoud Said in arts, Albert Bassili in timber. Four years earlier an Old Victorian Club had opened at the St. David's Building, above the Davies Bryan store at Alexandria's No.9 Sherif Street. Such was its success that it was eventually obliged to move to larger quarters at No.38 Zaghloul Boulevard. Membership was LE4 per annum.

Once the Old Victoria dinners were begun in Alexandria in 1924, the event became an important annual tradition in Victoria College's calendar of events. Similar reunions were also held at the Criterion restaurant in London during the summers, as well as at the Old Victorian Club's Cairo branch, at No.30 Savoy Chambers (later No. 7 Al Fadl Street.

Victoria College's 1936 Speech Day was another exercise in pomp and ceremony. Prime Minister Ali Maher presented the certificates and prizes while Admiral Sir Dudley Pond, British commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean Fleet, together with finance minister Ahmed Abdel Wahab Pasha, addressed an impressive array of distinguished notables and visitors.

Absent however was the British high commissioner, Sir Miles Lampson. In view of the recent death of King George, court and state were in official mourning in England. Before the end of the month it was the turn of Egypt's King Fouad to suddenly pass away.

When sixteen-year-old Farouk mounted Egypt's throne, his realm was experiencing enviable economic stability and unprecedented general wellbeing. The monarchy was at its peak, now that the belated Anglo-Egyptian Treaty was in its final stages of negotiations. With the participation of several Old Victorians, a better understanding between Cairo and London had been achieved. The delegates to London had the task of rectifying the anomalous situation created by Britain's unilateral and ambiguous 1922 declaration of Egypt's independence. A more defined relationship between Egypt and Great Britain had to be set out.

Meanwhile at Victoria College, which now boasted a 500-strong student body, Mr. Reed was still in charge. It was his 25th year of service, and the Old Victorian dinner that year included ex-prime ministers, cabinet ministers, consuls and financiers among the two hundred Old Victorians gathered to celebrate the Headmaster's silver jubilee. The old boys' network had grown in numbers and in influence. But at school, it was cricket as usual. Seniors aspired to become prefects and there were those among the prefects who aimed at becoming the next head boy. And the head boy not infrequently aspired to eventually become his country's prime minister.

Hotel San Stefano

School year 1939/40 hardly began when the school's premises were requisitioned by the British authorities. Under the terms of the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty, Britain still enjoyed strategic and logistical privileges in its former protectorate. Thus the school was turned into a naval and military hospital (64th General Hospital ), remaining off-limits to civilians for the next four school years. Henceforth, the students would do without their imposing buildings, the large classrooms, the great dining hall, the incomparable grounds and the recently constructed Birley Hall (1937) with its imposing stage and cinema.

Mr. Reed was summering in England when war broke out, and by the time he made it back to Alexandria for the school's official opening ceremony on Tuesday 10 October 1939, it had already moved to its temporary wartime premises, the Hotel and Casino San Stefano. While the hotel was not the perfect substitute, it boasted an amenity not previously available to students. Unlike its grand ballroom, the hotel's popular skating rink was kept intact and not subdivided into classrooms. The well-appointed suites were given to the masters, while the regular rooms were allocated to students.

The Old Victorians Association, cotton king Mohammed Farghali Bey presiding, launched a war charity drive. Most fund raising events centered around cricket matches between Old Victorians and various sports clubs. In addition, talks and lectures were given by rising literary figures, including the still unknown Lawrence Durrell.

As Italy's bombers flew over Alexandria in 1940, many parents were unwilling to send their children back to Victoria College. To cope with this unprecedented situation, the school's council decided to open a branch in Cairo. San Stefano was limited to Alexandrines and dayboys only, and was run by the second master, W. J. Scovil of University College, London.

Under Ralph Reed, the ad hoc Cairo Branch occupied the newly built premises of the Italian School in Shubra, confiscated the day Italy declared war on the Allies. Overnight, 100,000 Italian civilians living in Egypt had become enemy aliens, and their property sequestered. The new Italian school had excellent facilities. Built along neo-Fascist lines, it included an indoor swimming pool, a gymnasium, a science lab and a small theater. The adjoining four-and-a-half feddans were also cleared to make way for additional sports and playing fields.

Mr. Reed rented temporary private quarters for himself at the Smouha Buidligs (No. 6) located on Nabatat Street in Garden City before moving into the Shubra School. The school's kindergarten, meanwhile, was set up in Giza (behind the Swissair building) under the direction of Miss Whitworth. Victoria College Cairo Branch opened for business for the first time on Monday 7 October 1940.

In 1941, Prize-Giving Day was held on 1 July in Alexandria's San Stefano Hotel. Owing to wartime circumstances it was attended by no one of actual significance. Young men were fighting for their lives only a few hundred kilometers away, and for the first time since its creation, Victoria College was of secondary importance. Yet, since travel to Europe was no longer possible, the school was sought after like never before by the elite of the surrounding Arab states. Their best sons arrived wide-eyed from Saudi Arabia, Transjordan, Lebanon, Lahaj, Sudan and the Trucial Coast, inflating the ranks of what had been a primarily non-Arab student body.

As the situation worsened north of the Mediterranean, scions of European monarchies expanded the student body further so that Romanovs, Saxe-Coburgs, Hohenzollerns, Zogos and Glucksburgs rubbed shoulders with the Hashemites, Mahdis and al-Sharifs. While most were treated like regular students some stood out because of restrictions imposed upon them. The Albanian royals, the Zogos, for instance, were constantly trailed by massive bodyguards, which is perhaps why didn't last long at Victoria. Years later, many among the Arab elite students would meet again this time as major players in rising petrodollar economies.

From the ensuing generations of Victoria College students (from both Alexandria and Shubra) came many regional leaders, financiers, scientists and cultural lights. While the list is too long to relate in full, one can mention Saudi Arabia's Kamal Adham, Adnan Khashogji and Hisham Al Nazer (head boy); Palestine's Antonious(es), Khaled Shoman (Arab Bank Ltd.), Eugene Cotran (eminent British judge), Hazem Nusseibeh and Edward Said; Bahrain's Alirezas; Sudan's Mahdis and Merghanis as well as several other students who would later occupy senior cabinet posts including Mamoun Abdel Wahab Beheiry; the Hashemties including Jordan's King Kussein and Irak's King Feisal. From these two kingdoms came Zeid and Riad Al Rifai, Zaid Ibn Shaker and the Pashashis. All would hold key positions in their respective governments. There were also Constantine of the Hellenes, Simeon II of Bulgaria and the City of London's prince of finance Gilbert de Botton.

Among the scientists we find mathematican Sir Michel Atiyah a pioneer in the development of the K-theory. Atiyah's Lebanese father (Edward: An Arab Tells his Story) and brother (Patrick) also studied at Victoria College.

Likewise, the roster of Egyptians is chock-full with ministers, doctors, intellectuals, authors and performers. One of the most famous on this extensive list, Hollywood star Omar Sharif, still called Michel Y. Chalhoub in his school days, was also a great cricket player. Other member of the arts included painter Mahmoud Saiid and movie director Youssef Chahine.

The first postwar Speech Day took place in the school's Alexandria premises in June 1945. The transfer back from San Stefano had taken place the previous August. Attending was Sir Miles Lampson, downgraded, in accordance with the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936, to ambassador. As though to make up for this contretemps, he was subsequently made Lord Killearn on the recommendation of the British government.

Sanhoury Bey, the Minister of Education, was also present. Meager attendance overall, however, signaled that Victoria College was entering a new chapter in its history, one in which Britain was no longer considered a pre-eminent world power. Mr. Reed had been taken ill and was represented by both W. J. Scovil and John Rex Gynlais-Price acting headmasters of Victoria College Alexandria and Cairo respectively. (Scovil would become headmaster of VCA from September 1945 until August 1947).

New to Victoria College were some postwar arrivals--German students whose families represented the latest wave of political refugees in Egypt. They included two who would become well-known scientists, Peter Lauer and Michael Flaschentrager.

In January 1946 former head boy and ardent anglophile Sir Amin Osman Pasha (ex-minister of finance) was assassinated. The murder of Osman signaled that what had heretofore been considered an asset--being a protege of the British--was now a dangerous liability. Even those who had received the coveted KBE (with the designation "Sir") were now hiding it. Nationalism was mounting, and the slogan "Inglizi out!" was heard again and again.

Victoria College, long regarded a symbol of British cultural and political prestige in the Middle East was not loved by the nationalists. In his book An Arab Tells His Story, Old Victorian Edward Atiyah describes the prevailing sociopolitical climate, and argues that Victoria College and the other "exemplary" British educational establishments in Egypt were doomed to failure in the long run because of British shortsightedness and their absurd sense of superiority.

During the 1948 Speech Day it was announced that Victoria College Cairo (VCC) would transfer to Maadi as soon as new premises were completed. Egypt and Italy had reconciled, and the Italians wanted their Shubra School back. Headmaster J. C. Price, a graduate of St. Edmund's Canterbury and Jesus College Cambridge, was now in charge of the Cairo Branch and its 450 students. Victoria College Alexandria, with 500 students, was under the leadership Mr. Herbert William Barritt.

Competition between the Cairo and Alexandria branches grew fiercer each year, especially during the famous sports meets. Physical training and other out-of-class activities were more than ever a principle element in the curriculum. Yachting, squash, boxing, riding, swimming, tennis and fencing were now as important as association football and cricket.

At Victoria College Alexandria, the "Bassili" swimming pool was constructed and the "Goar" gymnasium refurbished. Meanwhile the new Victoria College Cairo premises in Digla, Maadi, designed by John Poltock and erected by Messrs. Braithwaite, included fields covering twenty feddans--ample space for all kinds of sports facilities. All that remained of the large New Zealand army base that had made its home in Digla during World War II was General Freyberg's swimming pool. Still in working condition, it was incorporated with the new school's sports and recreational amenities.

Yet, due to financial shortfalls, and despite disbursements of residual British war funds for the project, the opening of the new Maadi premises was repeatedly delayed, and didn't happen until the 1950/51 school year.

As a consequence of the political turmoil culminating in the July 1952 military coup that toppled King Farouk, the new Victoria College Cairo at Maadi never had a formal opening. Instead, a low profile oak and jacaranda tree-planting affair took place in Digla. This was followed weeks later, in May 1951, with a tea party attended by Mrs. Ralph Reed as guest of honor. Widowed since 20 August 1945 (Mr. Reed having died of Lung cancer), she was back in Cairo to visit old friends. Also present were British Council representative C. D. Dowell, chairman of the school's council William Roger Fanner, and Old Victorians Fares Sarofim, Mahmoud Abaza and Edward Atiyah. Mr. Price retired for medical reasons very shortly after the April tree-planting ceremony, and it was for Second Master Howell-Griffith, as acting headmaster, to represent the school's faculty at the tea party.

Although the new headmaster had not yet been officially appointed, it was known that Mr. Alan Guy Elliot-Smith, a graduate of Oriel College, Oxford, and former headmaster of Cheltenham College in Glocester, had accepted the post.

A liberal in Cheltenham, Elliot-Smith was considered somewhat conservative in Cairo. Assisting him in his new task were four new masters: Mr. Humphreys, the former headmaster of his own Public School in England, Mr. David, who was the son of a former headmaster at Rugby, Mr. Lennox Cooke, who had just gone around the world by bicycle, and Mr. Doyle.

On 2 May 1953, Victoria College Alexandria celebrated its 50th jubilee. During its half-century existence, the school had seen three legendary headmasters: Lias, Reed and Scovil. It now had 684 students comprising 28 different nationalities. Sir Edward Peel had replaced the late Sir Henry Barker as chairman of the school council. Attending the noteworthy occasion was the school's fourth student, Charles Antonious, together with his former French teacher Monsieur Georges Dumont. They had first met in 1902 at the school's original premises in Mazarita.

During the celebrations a letter was read by Sir Edward Peel whereby Egypt's president, General Mohammed Naguib, congratulated Victoria College for its 50th jubilee and expressed regret at not being able to attend personally. Headmaster Barritt presented the school's new coat of arms, designed by the late English and history master E. St. Leger Hill (from Keble College, Oxford), who had passed away the previous year. In their speeches, H.B. Carver and H. Rofe praised second master H.B. Rider (University College, London) and the master of the Lower School R. R. Parkhouse. Both masters had served Victoria College for over 30 years.

The following year Elliot-Smith found himself in a head-on collision with the new Middle East. Ever since its regal inauguration by Lord Cromer fifty years earlier, Victoria College had persistently adhered to a secular program--a sound policy, especially when dealing with students from over 30 different nationalities belonging to 10 different religions and sects. It hadn't made sense to meddle and introduce religion as a fundamental component of the school's curriculum. Not until now that is.

In January 1954 Victoria College's policy was put to the test by student Mansour Hassan, an ambitious and single-minded monitor. Using religion as his pretext he felt the urge to make a statement against what was commonly perceived as the floundering British hegemony. In the short term Hassan's religious crusade failed and the school's insightful secular policy prevailed. In the long run however, the young protestor unknowingly had the last say. Years later Hassan became a successful businessman and a sometime minister of information during the Sadat era.

In 1956, following the hapless Tripartite invasion, Elliot-Smith, the second master Stephen Howell-Griffith and their Alexandria counterparts, along with the College's entire British staff, were sacked and enjoined to leave Egypt. De-colonization had started, and the British were loosing ground fast. It wasn't easy for many of Victoria College's teachers and administrators, used to having the upper hand in these parts, when they were suddenly faced with an uncertain future. The lucky ones would find comparable positions in other British outposts.

But with colonialism winding up in Asia and Africa, including Sudan and Nigeria, not all of Victoria's masters were so fortunate. A particularly ill-fated example was Mr. Teegan, who after being dismissed from Cambridge had taught science at Victoria College Alexandria. After 1956 he ended up a homeless drunk at London's Paddington Station. His sad story somehow brought home the fact that the sun had finally set on what was left of Victorian pomp and circumstance.

After 53 years of British public school education in Egypt that had so greatly influenced educational and social development in the Middle East, the Old Boys had finally attained political and economic power. Ironically, their coming out coincided with the disappearance of everything British in the region. Just what Lord Cromer had dreaded fifty-six years earlier.

Despite the dissolution of Victoria College as a British Institution in Alexandria and Cairo in 1956, its hundreds of graduates, many of whom have distinguished themselves internationally, still keep in touch through the Old Victorian Association, with numerous meetings throughout the whole world. Particularly memorable was the reunion of "Old school mates of His Majesty King Hussein of Jordan" held in Amman in the spring of 1981. This was followed by one of the largest reunion ever held of Old Victorians, in Alexandria during September 1983, to commemorate the Diamond Jubilee of Victoria College.

|

|