|

egy.com suggests following articles

|

|

Several of my articles on Garden City were plagiarized word for word by novelist MEKKAWI SAID (winner of the Egyptian State price for literature!!!!) and re-published under his own name in a three-part series in El-Masry El-Youm daily in September 2015. Cheers to our "talented" literature prize awardee. Your pain his gain !!!

|

EGY.COM - LANDMARKS - CAIRO - HELIOPOLIS

MIDAN EL TAHRIR

Samir Raafat

Cairo Times, December 10, 1998

Sarpakis (L) and Aziz Bahari (R) buildings overlooking Midan al-Tahrir (photo courtesy Carmen Weinstein)

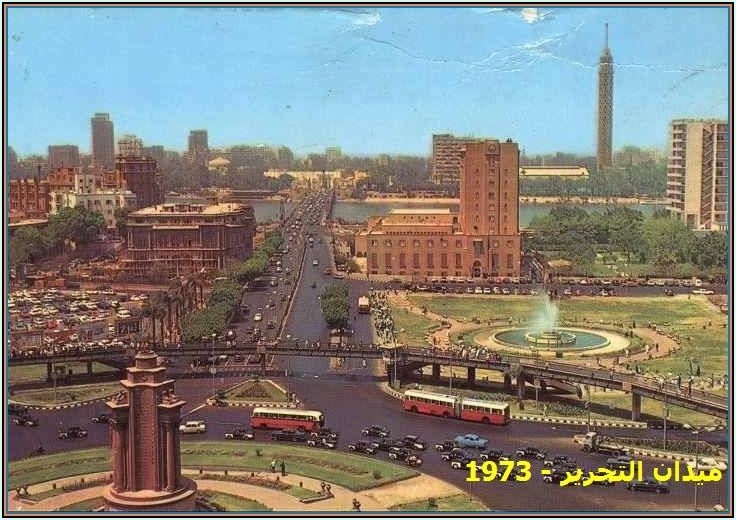

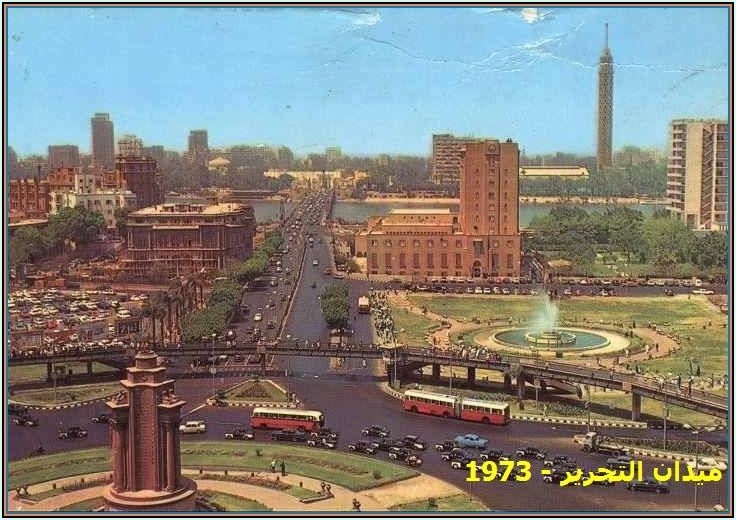

above: 1960s Tahrir Square esplanade seen from Egyptian Antiquities Museum

below: 1973 postcard evidencing pedestrian metal overpass with no Semiramis Intercontinental in sight

(photo courtesy the Maged Farag collection)

(photo courtesy the Maged Farag collection)

(photo courtesy CW)

Like ageless Cairo, Midan al-Tahrir cannot sit still. Whether reflecting the city's moods or the leadership's political agenda, the nation's most important plaza has gone from faux Champs de Mars to Stalinesque esplanade. Whenever a new regime feels the nation's capital needs a new look, the Midan has been the place to start.

Up to the 19th century the site of Midan al-Tahrir was a large swamp replenished faithfully with each summer flood. In his obsession to create a Paris-sur-Nil with long broad boulevards punctuated by squares and public gardens, Khedive Ismail pursued an ambitious canal scheme started by his father. One of its aims was to reclaim Cairo's western flank which would make room for the famous "Kasr" series: Kasr al-Aini, Kasr al-Aali, Kasr al-Dubara, Kasr al-Nil and Kasr al-Walda. Each represented a royal palace with Nilefront gardens.

The new palace district featured a magnificent square. Undoubtedly, Midan Ismailia was the city's biggest--larger even than Midans Mohammed Ali and Ibrahim Pasha (named for Ismail's grandfather and father respectively).

The new surrounding area, which people came to call Cairo's European Quarter, was al-Kahira al-Ismailia or Ismailia for short. Likewise, the city's first modern bridge was christened Kobri Ismail while the avenue running from it to the royal palace of Abdin was Sharia Kobri Ismail. Moreover, one of the palaces abutting the new Midan was Kasr al-Ismailia.

With so many namesakes of Khedive Ismail among Cairo's landmarks it would need a revolution to remove him from the face of the capital city. It did!

First to build on Midan Ismail was the khedive himself. For a while part of the palace was both home to Ismail's council of ministers as well as his ill-fated treasury. By then the state coffers had been drained on other khedivial building schemes.

Uniquely situated, with tracks linking it to Cairo's main railway station, Kasr al-Nil Palace became principle HQ for the British Army of Occupation after 1882 when beefy red-faced soldiers paraded by the Midan each morning and whenever necessary, shot Egyptian nationalists who marched upon the highly visible palace-turned-Inglizi-barracks.

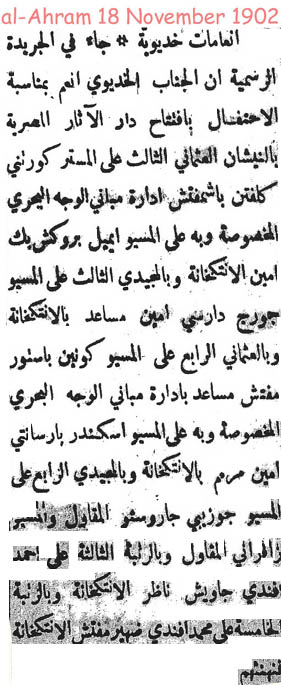

above: constructor, contractor, architect and curators of Egyptian Museum decorated by Khedive

Neo-classical Egyptian Antiquities Museum designed by Frenchman Marcel Dourgnon

laying groundstone celebrated on 23 January 1897 in presence of Khedive Abbas Hilmi II with commemorative gold medals distributed to VIP guests

and officially inaugurated 15 November 1902 by same khedive; its first curator Gaston Maspero Pasha

A new century brought new changes to the Midan. In March 1902 the Italian firm of Guissepe Garozzo & Francesco Zaffrani completed the Egyptian Museum designed by Frenchman Marcel Dourgnon so that the world's most prized antiquities collection could move the following November from Ismail's riverine Giza Palace (turned Zoo) to its present home.

Other fine structures fronting Midan Ismailia included the palace of the reigning khedive's (Abbas Hilmi II) sister (now Foreign Affairs, due for restoration), the palace of Ahmed Khairy Pasha (later, Nestor Ginaclis cigarette factory then Cairo University, now AUC), Kasr al-Ismailia (opposite the Kasr al-Nil Barracks, now gone) occupied for a while by Ghazi Mukhtar Pasha the Turkish High Commissioner to Egypt.

Midan Ismailia's northeastern flank, meanwhile, was home to large villas including Count Zogheb's Okel--Oriental palazzo. Passers-by took pleasure in admiring the neighborhood's railed-in gardens where proud Nubian bowabs stood guard behind closed iron gates. Not before long these villas were overtaken by smart apartment buildings belonging to affluent businessmen and merchants whose fathers and grandfathers--Messrs. Sarpakis, Zogheb, Soussa, Zaidan, Matossian and Bahari--had been lured to Egypt by Ismail's massive building schemes. Ironically, the only two properties on Midan al-Tahrir belonging to bona fide Egyptians were that of Ahmed Ihsan Bey (No. 11) a former wakeel of the Daira of Khadiga Hanim Talaat, and the villa of 1920s feminist Hoda Sharaawi. The latter was singled out for annihilation in 1970s. What was once a unique arabesque villa is today a large parking lot.

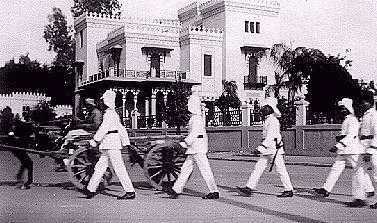

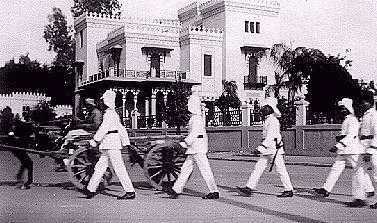

Unique picture of Villa Hoda Shaarawi No. 2 Kasr al-Nil Street with funeral procession in forefront (Raafat collection)

area previously occupied by Viceroy Saiid Pasha's Palace (Kasr al-Nil baracks) making way in early 1950s for Nile Hilton and Arab League buildings

seen at distance Egyptian Museum

right of photo villa Kout al-Koloub (ex-Cattaui)

left entrance to Kasr al-Nil Bridge

Further changes took place around the nation's largest plaza. For instance the Kasr al-Nil barracks evacuated by the British in 1947 were torn down in 1951-52 to make way for modern developments. These included Africa's first Hilton Hotel, an Arab League (designed by Mahmoud Riad) and what is today the former Arab Union Building.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the esplanade the mountainous Mogamaa building inaugurated in 1952 was about to become a beacon for Egypt's rising state-run bureaucracy-mediocracy.

On 2 September 1954, in its effort to remove all traces of the old regime, Egypt's new leadership renamed 15 Cairo streets and squares. Nasser had decreed all things "Ismailian" belonged in the doghouse so that Midan Ismailia became Midan al-Tahrir (Liberation Square).

Yet the big question remained, whose statue would be placed atop the colossal red granite pillar at the center of Cairo's broadest square especially now that the statue of Khedive Ismail, which ironically was due to be placed atop a granite pillar in July 1952, amidst a national celebration, would never see the day. Surely it must be crowned with the statue of al-Rais himself, clamored Nasser's devotees and praise writers.

The defeat of June 1967 removed any expectation of a statue. Instead, the pillar was removed in the 1980s when construction for the Cairo Metro began. Down also came the decade-old metal pedestrian footbridge that had so greatly contributed to the city's uglification. From then on, things could only get better.

Midan al-Tahrir's latest new look (currently in the making) includes a mega underground garage and several palm-decked gardens, welcome developments in a city choked by cars and pollution. As alterations continue, perhaps sometime in the not-too-distant future a commemoration for the square's original founder could materialize. Stranger things have happened at Midan al-Tahrir--or, dare I say, Ismail?

waving pre-1952 flag at epic Tahrir Square demonstration - Friday, 25 November 2011

Soussa Building in background

click here for panoramic view of 22 November 2011 demonstration by Mostafa Ibrahim

- Photo of museum courtesy Professor Carla Burri; of Kasr al-Nil bridge Ms. Denise Amoun; of Hoda Sharaawi villa Mr. Guy Wickenden; of granite pillar standing on roundabout Ms. Carmen Weinstein.

- The classical-Italianate red-granite colossus that adorned the square for three and a half decades cost about LE 100,000 at 1952 prices.

- Long before the granite colossus was removed from Midan al-Tahrir an amusing story came out in late 1958, when the deans of Egypt's fine art schools in Cairo and Alexandria squabbled among themselves on the adaptive re-use of the said pillar. One suggestion was that the history of Egypt's long struggle for freedom should be engraved on it. Another suggestion was that it becomes a memorial for the Unknown Soldier. A third suggestion was the launching of a sculpting competition among famous artists for an appropriate statue symbolizing Egypt's struggle. The winning statue would eventually be perched atop the granite structure. None of the above suggestion saw the day.

- The mountainous Mogamaa building on Tahrir Square is attributed to Dr. Kamal Ismail; he is also associated with the design of Alexandria University's neo-pharaonic Faculty of Engineering building.

- The only statue overlooking Midan El Tahrir is that of Auguste-Edouard Mariette Pasha designed by Denys Pierre Puech. It stands in the garden of the Egyptian Antiquities Museum.

- click on A TALE OF TWO BUILDINGS off Tahrir Square

Email your thoughts to egy.com

© Copyright Samir Raafat

Any commercial use of the data and/or content is prohibited

reproduction of photos from this website strictly forbidden

touts droits reserves