|

egy.com suggests following articles

|

|

Several of my articles on Garden City were plagiarized word for word by novelist MEKKAWI SAID (winner of the Egyptian State price for literature!!!!) and re-published under his own name in a three-part series in El-Masry El-Youm daily in September 2015. Cheers to our "talented" literature prize awardee. Your pain his gain !!!

|

EGY.COM - GIZA

THE HOUSE OF MOHAMMED MAHMOUD KHALIL

And How It Became A National Museum

by Samir Raafat

edited version appeared in The Egyptian Mail, May 6, 1995

and Cairo Times, April 30, 1998

part of this article was plagiarized in al-Ahram daily on 1 September 2010

French-style hotel particulier built for a Jewish banker, later site of a princely wedding, then home to a senate leader, finally an art museum

A BUILDING and its history are two fascinating things. Whenever an old house is given a new lease on life, it's a piece of local history that's been conserved. It's a link with the past.

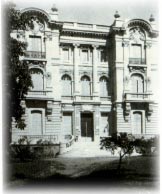

In Giza, two contemporary inter-visible yet starkly contrasting homes fit this bill. The one closer to the Nile is typical French-style hotel particulier.

The other, further inland, is outlandish rococo, today a run-down government school on Giza Street (opposite Mobil service station on Giza Avenue where it intersects Saluli Street). Nicknamed by some the gingerbread house in view of its red shingles, turrets and weather vanes, it was built at the turn of the 20th century for account of Abdel Halim Assem Pasha, a sometime khedivial field marshal and director of the awqaf department. Later, it became a pricey girls' school run by Ms Dagmar Berg before becoming the preserve of headmistress Madame Morin. But Morin was not the only Frenchwoman on the block for lording it in the house across Avenue Giza was her over-the-top compatriot Madame Mohammed Mahmoud Khalil born Emilienne Luce, formerly of the French theatre.

Our story today is about the house which became famous in the 1990s as the Mr. & Mrs. Mohamed Mahmoud Khalil Museum. Its story is unique in that it was successively occupied by a passionate art collector turned senate president, a wronged French widow and, later, by the president of the republic. Today it is an art museum.

THE FIRST OWNERS

If the account of Egypt's sometime boulevardier polo-player Victor Mansour Semeika (now a sprightly 90-something) was somewhat scanty, with some research and fact-checking it appears the French-style hotel particulier at No. 1 Kafour Street was built in 1905 as a country home for Raphael Suares (1846-1909) chairman of the famous Jewish banking house Suares Frères & Cie. Another indication for the age of this mansion is its beautiful glazed window which is dated 1907. Hence it is safe to assume this Nileside residence was completed that year or thereabouts

If the account of Egypt's sometime boulevardier polo-player Victor Mansour Semeika (now a sprightly 90-something) was somewhat scanty, with some research and fact-checking it appears the French-style hotel particulier at No. 1 Kafour Street was built in 1905 as a country home for Raphael Suares (1846-1909) chairman of the famous Jewish banking house Suares Frères & Cie. Another indication for the age of this mansion is its beautiful glazed window which is dated 1907. Hence it is safe to assume this Nileside residence was completed that year or thereabouts

"Following Suares's death his Giza house was sold by his heirs to Prince Omar Halim, a descendant of Viceroy Mohammed Ali," claims Semeika. Confirming Semeika's claim, al-Ahram announced in May 2, 1922, that Prince Omar Halim wed his relation Amina Omar Toussoun the previous day "at his Giza saray."

Sharing the same block with Prince Halim was King Fouad's eldest daughter, Princess Fawkia. She would much later lease her khedivial rococo palace and adjoining daira to the State Council/Conseil d'Etat--a judicial organ formed by royal decree in April 1941. "Married to Mahmoud Fakhry Pasha, Egypt's long-time minister to France, Princess Fawkia spent most of her time Paris," rambled Semeika. "It was probably at her urging that the Khalils purchased the house from Prince Omar Halim in 1928. The Fakhrys and Khalils were close friends."

THE MOHAMMED MAHMOUD KHALILS - the senator and the showgirl

1901 issue of Nantes Mondain praising Emilienne Luce as a young 20-year-old performer

L-R: the Khalils. Queen Farida with Mohammed Mahmoud Khalil and Richard Mosseri at photo exhibit

a typically scowling Mohammed Mahmoud Khalil standing next to HRH Princess Faiza

HIH Princess Neslisah (fur cape) standing second row (photo courtesy Prince Abbas Hilmi)

It was a happy day for Emilienne Hector Luce when she moved from No. 11 Kasr al-Nil Street (not far from Khalil Bey's legal practice at No. 6 Telegraph Street) into her new home Giza. The change of address was regarded a major move up society's totem pole. In time, her dour-faced, monocle-sporting grumpy husband would become a senior statesman and later senate president.

Khalil Bey's high station gave Emilienne endless pleasure at the thought she had become Cairo's leading hostess. Born into a modest French family of very limited means, she reveled at the role of grande dame, a part she played to perfection thanks to an earlier brush with the French stage, a fact which was not lost on Cairo's snobbish café society. According to Semeika "Emilienne was infinitely fond of frou-frou and trompète attire with an obsession for jewels which she wore for the most trifling occasion!"

And occasions were plenty in both Cairo and Paris for Khalil Bey had become a millionaire-businessman with a directoship in several blue-chip local and international companies, many of which had been created decades earlier by Monsieur Suares.

It was no secret Khalil Bey (1877-1953) was enamored with everything French. French wife, French cuisine, French theatre, French culture, French architecture and, thanks to his wife, French art. Between his marriage to Emilienne and the alleged purchase of Raphael Suares' mansion, Khalil Bey had corralled his sentimental and material urges. The Giza house on the Nile couldn't have been more Parisian in either style or taste, and the decor was of the finest quality.

It was no secret Khalil Bey (1877-1953) was enamored with everything French. French wife, French cuisine, French theatre, French culture, French architecture and, thanks to his wife, French art. Between his marriage to Emilienne and the alleged purchase of Raphael Suares' mansion, Khalil Bey had corralled his sentimental and material urges. The Giza house on the Nile couldn't have been more Parisian in either style or taste, and the decor was of the finest quality.

Egged on by his wife, Khalil Bey became a compulsive art collector. Together with Prince Youssef Kamal (Victor Semeika's long-time friend and benefactor), Emile Miriel, Youssef Cattaui Pasha, Ali Ibrahim Pasha, Mohammed Taher Pasha, Henri Naus Bey, Sir John Home, Sir Robert Rolo, Aldo Ambron, Charles Boeglin and G. Fouad Abdel Malek (who had created Le Salon du Caire), Khalil Bey founded in 1924 La Société des Amis de l'Art.

Years later, the French reciprocated Khalil Bey's love for France rewarding him with the title of Correspondant de l'Académie des Beaux Arts and the Grand Cordon de la Légion d'Honneur. The Italians followed suit with the Grand Cross of Maurice & Lazarre. Moreover, the huge success of the 1937 Exposition France-Egypte earned Khalil Bey a seat in the Institut de France. Naturally, he was already a member of the Institut d'Egypte.

The Khalil art collection in Giza was rated one of the best in Cairo comparable in value to those belonging to the great private collectors of Alexandria such as Sir Henry Barker, Alexandre Benachi, Emanuel Constanino, Jacques Matossian, Charles de Menashe, Max Rolo, Gregoire Sarkissian and Edwin Goar.

Cairo too had its art-thirsty clique including Carlo Grassi, Mohammed Sultan, Levi de Benzion, Fortuné Martino and Leon Rolin. Even though he was an absentee landlord, one must include Baron Empain in view of his exquisite collection of Gobelins adorning the walls of his Heliopolis Hindu Palace.

The Khalils prided themselves in having Egypt's single best collection of European impressionist and modern paintings belonging to the French 1830's school. At No. 1 Kafour Street one could concurrently admire Champmartin, Daumier, Ricard, Delacroix and Toulouse Lautrec. The Khalil home was also a depository of several Renoirs, Pissaros, Trovons, Sisleys, Millets, Moticellis, Milots and Diaz de la Penas. And one should not forget Van Gogh's Fleurs collection.

The list goes on. Statuettes and marble busts included a work each by Rodin and Cajou. There was also the fabulous jade collection. All these treasures were carefully listed in his 1933 inventory.

More works of art were forthcoming as European dealers hurriedly unloaded their troves the eve of WW2. Khalil Bey was a reliable taker. Each trip to Paris was a shopping extravaganza of French masters and objects d'arts. The Giza mansion was turning into the largest repository of French works this side of the Mediterranean. And since a curator was desperately lacking, one was quickly found in the person of international connoisseur Richard Mosseri. Mosseri came highly recommended by his Cairo cousins with whom Khalil maintained tight banking relations through Banque Nessim Mosseri & Cie.

An Eliza Doolittle-on-the-Nile, Emilienne could hardly believe her good fortune. She had made it as society's Queen Bee, which in Egypt had the Paris effect multiplied by four. Not only were the Khalils overlords of Giza's most famous mansion but as minister of agriculture in Moustafa al-Nahas Wafdist 1937 government, and later as senate president, Khalil Bey entertained the best. Cairo's social calendar reserved the first day of each month for Emilienne's 'at home'. Entertainment during WW2 was even racier than usual when Cairo, by some bizarre twist, became home to both pro-Nazi Vichy diplomats and those representing the Free French. Emilienne was in a spiraling tizzy.

Moreover, Emilienne had recently heard over the gilded WW2 Cairo grapevine that Khalil Bey was recommended for high office with a pashahood appended. The idea was however unthinkable to Sir Miles Lampson who, as British ambassador, harvested an intense dislike for the senator describing him as "a poisonous snake who spreads enemy propaganda and defeatist talk." The senior British diplomat went as far as suggesting that Prime Minister Nahas Pasha place Khalil Bey under house arrest. Although the crafty Nahas declined the ambassador's recommendation, his rejoinder, although in essence true, was most unflattering: "Khalil is a senator and a completely worthless creature therefore not deserving of incarceration!"

Khalil would therefore spend WW2 in sumptuous surroundings. Yet opulence notwithstanding, one thing was lacking at the Giza palace. Mohammed and Emilienne Khalil's marriage remained fruitless. Khalil bey was impotent. They had no common heir to perpetuate their memory. Once they were gone from the realm of the living it would be a matter of time before they'd be forgotten, and their enviable art collection auctioned out and dispersed around the globe.

Perhaps sensing the end was near and with such a large fortune invested in art and other singular assets, Khalil Bey, a lawyer by profession, drew up a mammoth legal agreement on 20 December 1953. In it he bequeathed Emilienne one third of his estate. In other words, his wife of five decades would appropriate his priceless art collection. It was also understood that in line with Shari'a (Islamic law), Emilienne would also inherit 1/4 of the remainder of Khalil's vast assets. Importantly, there was no mention whatsoever in the December agreement of a male offspring. Had there been one, Emilienne's share would have dwindled to 1/8 with the balance going to the dauphin.

Khalil's munificent 20 December 1953 inheritance arrangement which conformed with Shari'a law, covered one third of his total assets. These included shares, securities and government bonds located at a variety of banks including Banque Mosseri, the National Bank of Egypt, Banque Misr and the Shark Insurance Co. There were title and deeds to vast landed properties across Egypt including farms in Fayum, Kafr Saiid (Behera) as well as prime agricultural land located at Geziret al-Dahab and Manial Shiha in Giza. Presumably these would continue to be managed by the busy Khalil daira located at No. 14 Soliman Pasha Street.

Yet why, one may ask, was No. 1 Kafour Street omitted from the December 1953 bequest? After all this landmark mansion was the much-recognized jewel in the Khalil crown.

There was no mention of the palatial home simply because it had already been conferred by Mohammed Mahmoud Khalil to Emilienne on 3 April 1947. The related deed bore the required notary public stamp dated 9 May 1947 under serial No. 4135.

If Emilienne felt secure in the knowledge the roof above her was hers and hers alone, the eleventh-hour December 1953 bequest was meant to give her added financial and moral security. Or so she thought at the time!

Shortly after naming Emilenne his benefactress, Mohammed Mahmoud Khalil suffered a massive heart attack in Paris. France's leading cardiologist, professor Mellies could not intervene. It was a matter of hours.

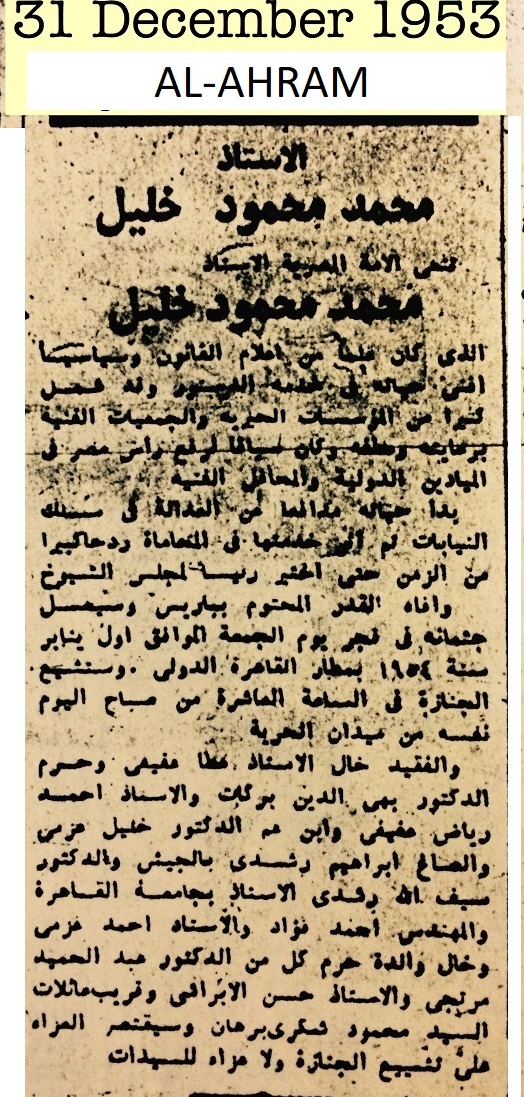

Mohammed Mahmoud Khalil passed away on 27 December 1953, a week to the day after initialing his large bequest to Emilienne. Contrary to what has become common legend today, he died NEVER KNOWING his Nile-side mansion and art collection would one day become one of Egypt's most respected museums.

The former senate president received a befitting funerary service at the Paris Mosque with Egyptian and Arab diplomats in attendance. In gratitude to its old friend France rolled out the red-carpet giving Khalil Bey a state send-off. To do the honors were General Catroux, a friend from the old days. And representing the Quai d'Orsay was de la Chaviniere, director of protocol accompanied by de Bourbon-Busset director of cultural affairs. Also present were Charles Braibant director of the national archives along with Hautecoeur and Dropsi, both former members of the French Academy. Also, in attendance was Monsieur Cornu secretary of the Beaux-Arts together with Frangoulis of the Diplomatic Academy. Even the Comedie Française was represented quite befittingly by Mme Jeanne Boitel.

Khalil Bey's body was covered with Egypt's green flag on which rested his Academy's costume, his bicorne hat and his multifarious decorations.

The French press, notably Le Figaro, ran an elaborate obituary. In Egypt, Ambassador Couve de Murville eulogized Khalil Bey during the embassy's traditional New Year's address with these words: "France had lost its best friend ever in Egypt."

Worth noting is how Sir Miles Lampson, now a retired peer in England, refrained from sending a note of sympathy to the deceased's wife.

The eulogies said and done, Emilliene's mourning was cut short by a series of court summons served by an unanticipated third-party clamoring for a giant share in Mohammed Mahmoud Khalil's estate.

A savory scandal was about to shake the core of Egyptian high society!

It suddenly appeared the only thing separating Emilienne from the poorhouse was her late husband's bequest of December 1953. And even that was being contested.

The 1953 agreement however proved irrevocable during the protracted legal battle that ensued pitting the country's top legal minds against each other.

It was now evident the main reason behind Mohammed Mahmoud Khalil's eleventh-hour December 1953 inheritance arrangement had more to do with penance than inheritance tax. In other words, it was directly linked to what had been vastly rumored a few years earlier and later ascertained by Emilienne herself.

To her absolute stupefaction Emilienne had discovered in 1946 that smitten by a young Circassian beauty, her 70+ year-old senator-husband had very briefly engaged in an ephemeral affair. Not only was the lady in question Cairo's most beautiful catch but she also had the class to match. Although the alleged relationship lasted a twinkling, "somehow..." claimed the scorned Emilienne sarcastically, "... by divine intervention a male heir was miraculously produced!" Emilienne had learnt through the grapevine the identity of the child's biological father but in order to moot the spiraling scandal kept silent for fear of a backlash. Prime minister Nahas had repeatedly implored Senator Khalil Bey not to contest the paternity for fear that the ensuing scandal would most certainly lead to the downfall of the already shaky sitting Wafd government. In his despairing predicament, the Senate President reluctantly complied.

To her absolute stupefaction Emilienne had discovered in 1946 that smitten by a young Circassian beauty, her 70+ year-old senator-husband had very briefly engaged in an ephemeral affair. Not only was the lady in question Cairo's most beautiful catch but she also had the class to match. Although the alleged relationship lasted a twinkling, "somehow..." claimed the scorned Emilienne sarcastically, "... by divine intervention a male heir was miraculously produced!" Emilienne had learnt through the grapevine the identity of the child's biological father but in order to moot the spiraling scandal kept silent for fear of a backlash. Prime minister Nahas had repeatedly implored Senator Khalil Bey not to contest the paternity for fear that the ensuing scandal would most certainly lead to the downfall of the already shaky sitting Wafd government. In his despairing predicament, the Senate President reluctantly complied.

Ergo, could the successive and timely bequests to Emilienne be interpreted as the supplications of a repentant husband? An expiring ex-senator who had momentarily sinned and begged forgiveness from his lifelong companion... St. Emilienne!

THE MUSEUM

If she forgave her late husband's simulated cheating preferring to write it off as a retour d'age, Emilienne's sense of revenge from the 'miracle' child and his mother intensified. She would counter-attack.

First things first. The heir "apparent" was not mentioned in Khalil Bey's al-Ahram obituary. It was as though he did not exist.

Second. Khalil Bey's blood relations were galvanized to contest the paternity. Was it not common knowledge in Cairo circles that the senator's problem was not so much his having been unfaithful but simply that he was unfruitful--sterile and unable to conceive! Understandably, his living relatives stood to gain considerably by contesting the paternity of the alleged son.

The above failing, the grieving widow made it evidently clear no one was going to displace her from No. 1 Kafour Street, dead or alive! No presumptive heir would enjoy or inherit the priceless wonders she and her husband had collected ever since they were married in 1901. As mentioned earlier, the mansion and all it contained had already been bequeathed to Emilienne by her husband in 1947, the birth year of the miracle child. Hence, any legal attempts to claim the mansion at the request of the "dauphin's" mother were quickly mooted.

Appointing the son of veteran lawyer and family friend Zaki al-Ibrahsi Pasha as her estate executor, Emilienne drew up a new will notarizing it (No. 42/1954) at the Giza Notary Public on 30 June 1954. The terms were unequivocal. Upon her death, the mansion at No. 1 Kafour Street, its garden and annexes and all its contents would go to the State. The house would become a museum to perpetuate her and her husband's memory to the exclusion of any other claimants. Hassan Ibrashy, now a rising lawyer, was executor of Emilienne's estate.

Emilienne Hector Luce a.k.a. Madame Mohammed Mahmoud Khalil died on 19 March 1960.

True to Emilienne's wishes the State was more than happy to comply with her bequest. Thus, a museum on the banks of the Nile was born subsequently inaugurated in 1962 by Sarwat Okasha, the then-minister of culture and temporary trustee of the mansion and its belongings.

From that account and contrary to prevailing misinformed tales, it was a scorned woman's fury and not Khalil Bey's generosity that enabled Egypt to legally acquire one of its finest art museums. Point finale!

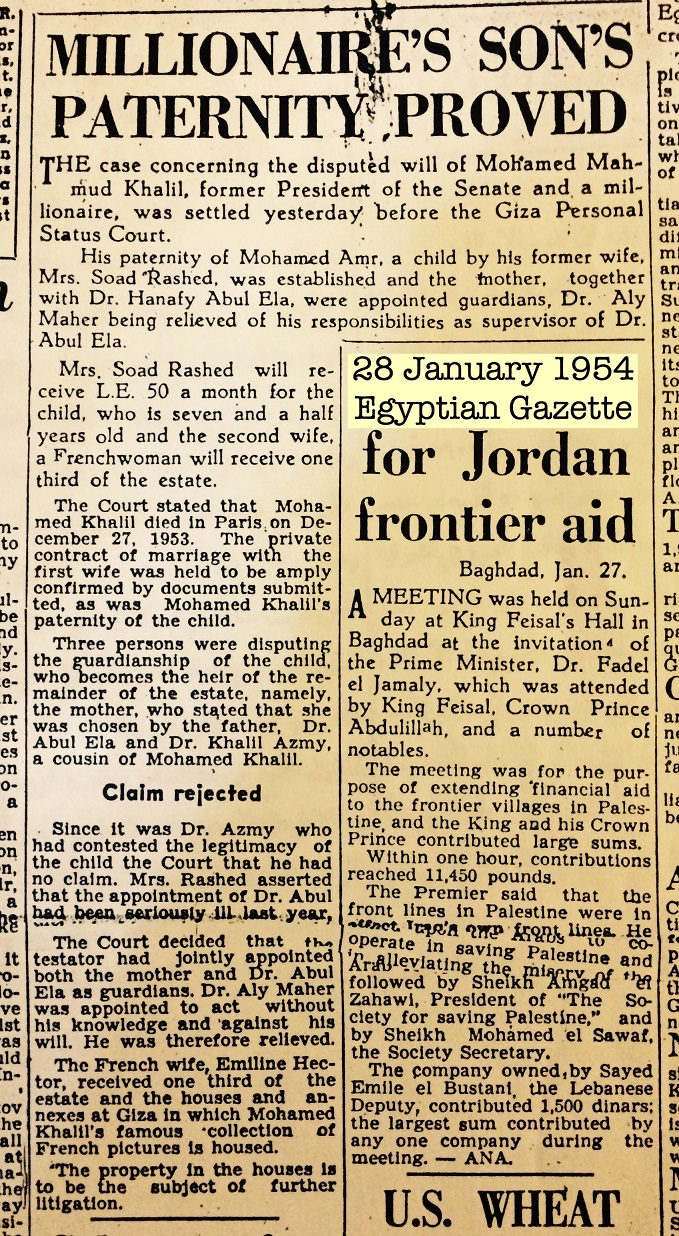

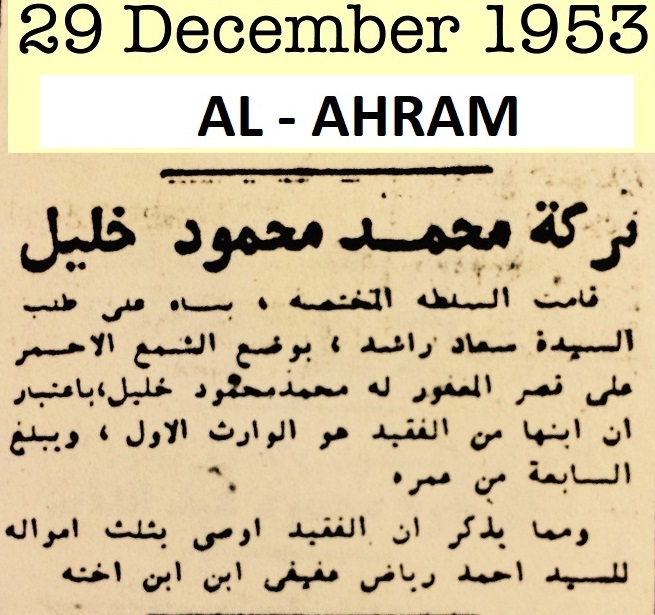

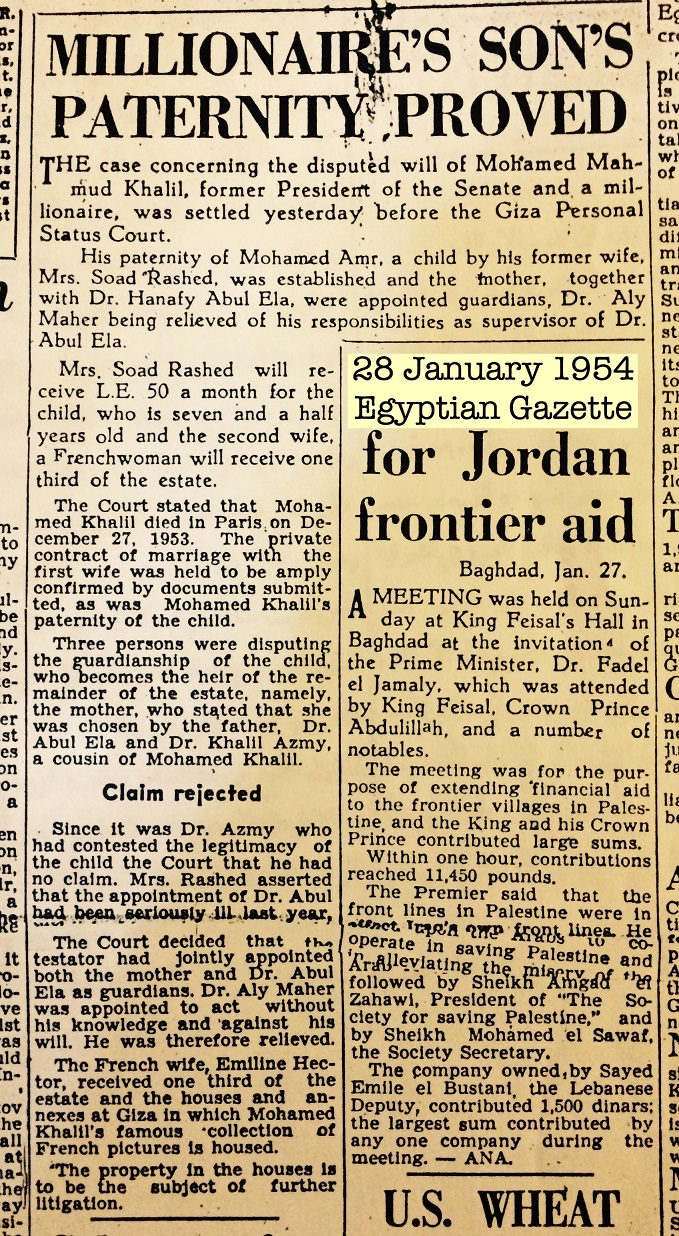

Mohammed Mahmoud Khalil dies in Paris on 27 December 1953. Following day Soad Rashed seeks court order to sequester the Khalil mansion at No 1 Kafour Street, Giza to safeguard the property and its priceless contents for her 7-year-old son

Mohammed Mahmoud Khalil obituary naming his next of kin. No mention of son

paternity of infant proved. Soad Rashed and her sometime mentor-lawyer Hanafi Abou-Ella named trustees. Emilienne's claim to mansion ownership recognized by state

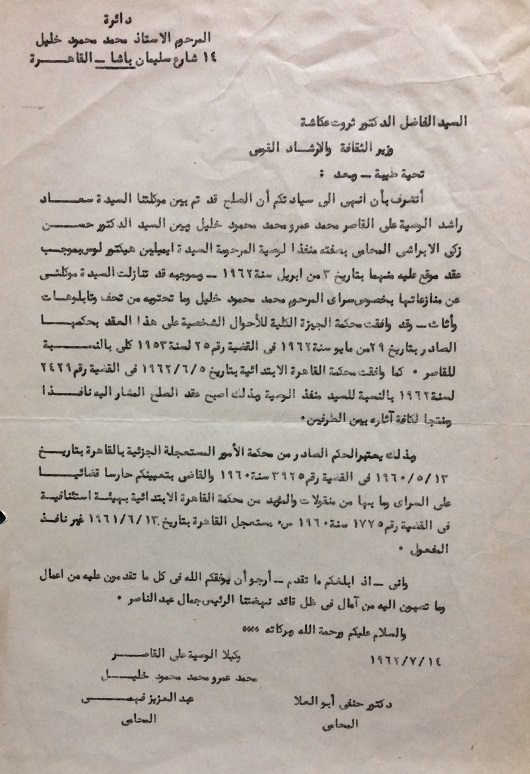

14 July 1962 handover of Khalil mansion to the state as per Emilienne's last testament

THE PRESIDENCY

Two decades later, it would require the highest authority in the state to temporarily bend Emilienne's ironclad codicils. Just before he succeeded Gamal Abdel Nasser, Anwar al-Sadat had moved into the former house of Charles Castro directly opposite No. 1 Kafour Street. Once president of Egypt, Sadat needed new space for his executive branch just as he needed a nearby Heliopad for his frequent travels.

Hence, in defiance to Emilienne's ruling, the Khalil Museum was expropriated to accommodate the president's men while the fronting river foreshore was asphalted enabling the presidential chopper to land and take off.

Down came the paintings. Up came the credenzas, desks, telephones and telex machines. The Mohammed Mahmoud Khalil art collection was relocated at No.16 Gezira Street in Zamalek, in a confiscated palace belonging to a former member of the Mohammed Ali dynasty. It was there that the Khalil treasures would remain for twenty odd years.

Sadat's sudden demise in October 1981 brought on a period of uncertainty. What would become of the former Khalil mansion? Would Emilienne's wishes be upheld or would they be ignored? The answer came twelve years later when Egypt's incumbent president Mubarak inaugurated the restored Mr. and Mrs. Mohammed Mahmoud Khalil Museum in its original setting.

In turn, No. 1 Kafour Street was home to a Jewish banker, a minor prince of Egypt, a senate president and his tenacious French wife, a private museum open to the public and an executive office for the president of the republic. So in fact this beautiful house built at the dawn of this century represents much more than a location on a Giza street map. It is an evocative address synonymous to history, culture and power.

OK, WHO WAS THE RAPHAEL SUARES THAT VICTOR SEMEIKA TALKED ABOUT?

Had it not been for the Suares brothers--Felix, Joseph, Raphael--and Sir Ernest Cassel of London, the man best known in Egypt for engineering the sale of

Daira Saneya, there may have not been a National Bank of Egypt.

In 1898 the above gentlemen teamed up to launch Egypt's first bank of issue. Seventeen years earlier the Suares's had formed with others the Credit Foncier Egyptien, which, after a bumpy start in Alexandria, became Egypt's leading bank. Its imposing Cairo branch inaugurated in 1904, is today headquarters of the Arab International Bank on Abdel Khalek Sarwat Street.

Raphael Suares was a principal shareholder in several of Egypt's transport ventures including railways in Upper Egypt and the famous Bab al-Louk--Helwan line. Decades later it would become the nucleus of Cairo's metro system. Helwan, then an exclusive thermal spa and home to bankers and pashas was heavily indebted to the Suares brothers for its electricity, its casinos and its health spas.

Recognized as Egypt's leading real-estate tycoons, the Suares brothers owned large chunks of property in what was then called the Ismailia district, an area stretching from Cairo's Midan al-Opera to Midan Ismail (today, Midan al-Tahrir). Hence, the reason why Midan Moustafa Kamel was called Rondpoint Suares until 1939.

It was from his nearby Cairo townhouse that Raphael Suares's funeral procession started out on 28 April 1909, attended by members of the Khedivial family. Subsequently the house was sold to the Land Mortgage Bank of Egypt, which turned it into its headquarters.

But for a man who had everything, Suares' marriage was childless. He had no son to carry his name and fortune into the 20th century. His heirs were several nephews and nieces and his adopted daughter, Alix Marthe Louise Frezet. Alix was his late wife's--Marie-Rose Biot's-- natural daughter from an earlier marriage.

Between April 1898 and August 1908, Alix was listed in several Gotha-related publications as Princess Fazil (Princess Facile snipped her detractors). Her husband, Prince Ali Mustafa Fazil, was a great grandson of Viceroy Mohammed Ali. A few months before he died, Raphael Suares, in his capacity of principal shareholder of the Société General des Sucreries et de la Rafinnerie, played host to Khedive Abbas Hilmi during the latter's February 1909 Upper Egypt tour. The meeting took place at the sugar refinery of Naga Hamadi. It was in the presence of his royal guest and the members of the Sugar Company's board that Suares read the welcome speech.

Impressed with what he saw, the Khedive reply consisted of an imperial firman which conferred on Suares the Ottoman Grand Order of the Medjidieh First Class. "Votre nom, Monsieur Suares, est étroitement uni a toutes les entreprises utiles du pays. Je suis heureux de vous éxprimer publiquement ma gratitude en vous confèrant la premiere classe de la Médjidieh."

Attending this historic visit was Alix Fazil who presented her younger son to his royal relation.

Not present at this landmark meeting was one of Raphael Suares's young aides. Many years later, the promising Talaat Harb, would create along with other Suares relations and protégés, the Banque Misr group of companies earning him the title of 'father of Egyptian commercial enterprise.' His statue today stands at the center of ex-Soliman Pasha Square (now Talaat Harb), facing the former Rondpoint Suares at the southern end of Kasr al-Nil Street. Coincidence?

When Suares died, Princess Fazil, now divorced from her husband, remarried in London Baron Constantin Gerhard von Carnap. Her sons, Ibrahim Fazil (1901-78) and Said Fazil were sent to boarding school in England where they received a British education. Both subsequently served as officers in the British army. Whatever the reason, they felt no compulsion about their mother country. England was their home so much so that their descendants today go by the name Foxwood having changed their name by Deed Poll

Email your thoughts to egy.com

© Copyright Samir Raafat

Any commercial use of the data and/or content is prohibited

reproduction of photos from this website strictly forbidden

touts droits reserves

If the account of Egypt's sometime boulevardier polo-player Victor Mansour Semeika (now a sprightly 90-something) was somewhat scanty, with some research and fact-checking it appears the French-style hotel particulier at No. 1 Kafour Street was built in 1905 as a country home for Raphael Suares (1846-1909) chairman of the famous Jewish banking house Suares Frères & Cie. Another indication for the age of this mansion is its beautiful glazed window which is dated 1907. Hence it is safe to assume this Nileside residence was completed that year or thereabouts

If the account of Egypt's sometime boulevardier polo-player Victor Mansour Semeika (now a sprightly 90-something) was somewhat scanty, with some research and fact-checking it appears the French-style hotel particulier at No. 1 Kafour Street was built in 1905 as a country home for Raphael Suares (1846-1909) chairman of the famous Jewish banking house Suares Frères & Cie. Another indication for the age of this mansion is its beautiful glazed window which is dated 1907. Hence it is safe to assume this Nileside residence was completed that year or thereabouts

It was no secret Khalil Bey (1877-1953) was enamored with everything French. French wife, French cuisine, French theatre, French culture, French architecture and, thanks to his wife, French art. Between his marriage to Emilienne and the alleged purchase of Raphael Suares' mansion, Khalil Bey had corralled his sentimental and material urges. The Giza house on the Nile couldn't have been more Parisian in either style or taste, and the decor was of the finest quality.

It was no secret Khalil Bey (1877-1953) was enamored with everything French. French wife, French cuisine, French theatre, French culture, French architecture and, thanks to his wife, French art. Between his marriage to Emilienne and the alleged purchase of Raphael Suares' mansion, Khalil Bey had corralled his sentimental and material urges. The Giza house on the Nile couldn't have been more Parisian in either style or taste, and the decor was of the finest quality.

To her absolute stupefaction Emilienne had discovered in 1946 that smitten by a young Circassian beauty, her 70+ year-old senator-husband had very briefly engaged in an ephemeral affair. Not only was the lady in question Cairo's most beautiful catch but she also had the class to match. Although the alleged relationship lasted a twinkling, "somehow..." claimed the scorned Emilienne sarcastically, "... by divine intervention a male heir was miraculously produced!" Emilienne had learnt through the grapevine the identity of the child's biological father but in order to moot the spiraling scandal kept silent for fear of a backlash. Prime minister Nahas had repeatedly implored Senator Khalil Bey not to contest the paternity for fear that the ensuing scandal would most certainly lead to the downfall of the already shaky sitting Wafd government. In his despairing predicament, the Senate President reluctantly complied.

To her absolute stupefaction Emilienne had discovered in 1946 that smitten by a young Circassian beauty, her 70+ year-old senator-husband had very briefly engaged in an ephemeral affair. Not only was the lady in question Cairo's most beautiful catch but she also had the class to match. Although the alleged relationship lasted a twinkling, "somehow..." claimed the scorned Emilienne sarcastically, "... by divine intervention a male heir was miraculously produced!" Emilienne had learnt through the grapevine the identity of the child's biological father but in order to moot the spiraling scandal kept silent for fear of a backlash. Prime minister Nahas had repeatedly implored Senator Khalil Bey not to contest the paternity for fear that the ensuing scandal would most certainly lead to the downfall of the already shaky sitting Wafd government. In his despairing predicament, the Senate President reluctantly complied.