GEZIRA SPORTING CLUB MILESTONES

by Samir Raafat

Egyptian Mail, February 10-17, 1996

wartime cricket match (1943)

|

|

|

|

|

Cheers to our "talented" literature prize awardee. Your pain his gain !!!

|

|

|

EGY.COM - ZAMALEK

|

|

GEZIRA SPORTING CLUB MILESTONES

by Samir Raafat

Egyptian Mail, February 10-17, 1996

wartime cricket match (1943)

Various testimonials summarize the socio-political setting surrounding the creation of the Gezira Sporting Club by a unique group of empire builders referred to locally as "Anglo-Egyptians." With the imminent Hong Kong Handover in 1997, these individuals, whose likes could be found in the British Raj, in East Africa and in South East Asia, are members of a now extinct colonial caste.

1880s - 1914

"Cairo has several clubs, but only two are patronized by the best English people, for the luxurious Khedivial is essentially a club for foreigners and Gyppies. I refer to the Turf Club and the Khedivial Sporting Club. With the latter no fault can be found. Its subscription is low and it gives members all kinds of advantages and attractions. It would be charming even if it had no sports, for its wealth of flowers, its broad stretches of turf, its southern trees and beauty". Douglas Sladen wrote this account in Egypt and the English (London, 1908). His use of the term 'foreigners' meant anyone not British with the exception of the indigenous population. The term 'Gyppies' was one of the terms Sladen and his British contemporaries denoted native Egyptians.

Percy F. Martin's Egypt - Old And New (London, 1923), relates how: "The Gezirah Sporting Club of which Captain Hope-Johnson has been, for some years, the very popular and enterprising secretary, is reached in about ten minutes by carriage from either the Continental or Shepheard's Hotel in Cairo. Whilst its hospitable doors have always been opened to visitors non-resident in the capital, the sole requisite for entrance having been a personal introduction from a member, exception has been taken not without some reason to the policy which tends to bring about the exclusion of the Egyptians from any active participation in the management of the sports; neither have they been encouraged to become members of the Club, except in certain cases. None the less, the institution was primarily established partly with their assistance and certainly with the aid of their monetary contributions."

"Want of consideration for the want of the native population particularly of the better classes, permanently inhabiting the countries in which British men and women but temporarily reside, has frequently provided one of the greatest drawbacks to the gaining of popularity and friendship, even where other of our national virtues are generously recognized. It was once said by George Elliot that British selfishness is so robust and many-clutching that, well encouraged, it easily devours all sustenance away from our poor little scruples."

"No actual rule as to the exclusion of the Egyptians from the Sporting Club exists; but the natives are not welcomed, and doubtless find themselves ordinarily de trop."

W. Basil Worsfold, an observant literary barrister who visited Egypt in the winter of 1898-9, remarked in The Redemption Of Egypt that "The English resident have no more to do with the picturesque ruins and mud-heaps of Medieval Cairo than the average West End Londoner has to do with the Mile End Road and Tower Hamlets. Except when they wanted to show a visitor the tombs of the Khalifs or the Pyramids they only left their villas in the European quarter to drive to their offices or the Gezira Club."

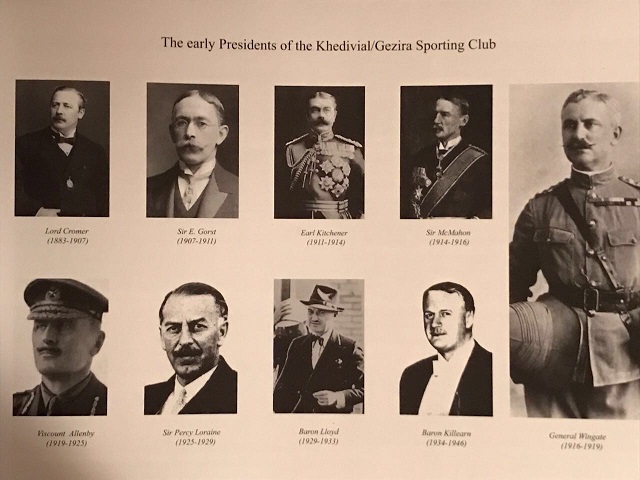

In The British In Egypt Peter Mansfield writes of Lord Kitchener: "In another respect he went a long way towards reversing Gorst's policies. Whereas Gorst had shifted executive responsibilities on to Egyptians wherever possible, under Kitchener the number of British in the higher positions now rapidly increased again. But Kitchener was not in favor of British social exclusiveness. In India he deplored it and blamed it on the club system, in Cairo he pursued Gorst's habit of inviting as many Egyptians as possible to the agency [embassy] with the difference that he does not appear to have been criticized by the British and other Europeans communities as a consequence. He did take fairly ruthless action to force the Egyptians members to resign from the famous Gezira Club, but this was not out of any belief in social 'apartheid' but because complaints that members of the Khedive's circles were using the club to express anti-British opinions. With Kitchener's approval another club was opened with mixed membership."

In Sir Ronald Storr's Orientations we find the following: "The Turf Club, situated in the Sharia al-Maghrabi [now Adly] next to the self-respecting but architecturally painful Sephardi Synagogue, was the fenced city of refuge of the higher British community, many of whom spent anything between one and five hours daily within its walls. The Sporting Club at Gezira, on an admirable site presented in the eighties by the Khedive Tewfik and improved since then almost out of recognition, was the other British headquarters. It was difficult for foreigners to be elected and not easy for Egyptians even to make use of either Club; as I discovered by the glances cast in my direction when I came in with one of the few Egyptian members to play tennis."

In Sir Ronald Storr's Orientations we find the following: "The Turf Club, situated in the Sharia al-Maghrabi [now Adly] next to the self-respecting but architecturally painful Sephardi Synagogue, was the fenced city of refuge of the higher British community, many of whom spent anything between one and five hours daily within its walls. The Sporting Club at Gezira, on an admirable site presented in the eighties by the Khedive Tewfik and improved since then almost out of recognition, was the other British headquarters. It was difficult for foreigners to be elected and not easy for Egyptians even to make use of either Club; as I discovered by the glances cast in my direction when I came in with one of the few Egyptian members to play tennis."

Storrs was with the British Consulate when it was upgraded to a 'Residency' in 1915 when Egypt was declared a British Protectorate. As Oriental Secretary (No. 2 man) under Cromer, he learned first-hand about British high-handedness. It would have been difficult not to, considering he served under two of the greatest imperialists: Cromer and Kitchener. The Egyptian tennis player he mentions in his Gezira passage eventually became prime minister. Who could have blamed this Egyptian statesman for carrying the tiniest of grudges towards the Inglizi!

And who could have blamed the hospitality-minded Egyptians if they regarded the Gezira and Turf clubs as grotesque imperialist institutions. By virtue of its definition a club means bringing together birds of a feather who share common interests while keeping everybody else out through a system of quotas and membership ceilings. Yet, try explaining that to the ahlan-wa-sahlan type Egyptians or Indians who found it hard to accept that anyone would want to keep them out.

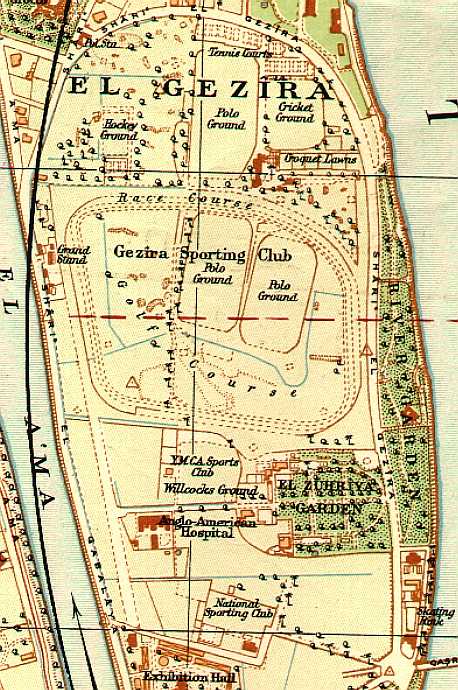

above: a 1930's map. Below: a google earth map 2002

THE CLUB

The palm-decked island of Boulak (now Gezira-Zamalek) was added to the vice-regal ciftlik (estate) of Giza during Khedive Ismail's reign. The island's landscaping and nurseries were the work of Delchevalerie, the former landscaper of the French capital. For the Khedive's benefit, a koshk or kiosk was erected in the center of the island near its eastern shore.

It was a few years later, that a U-shaped baroque summer saray or palace (now the Marriott Hotel) was added nearby. The Gezira Palace, as it was originally called, was designed by Julius Franz Pasha and decorated both externally and internally (in part) by Karl von Diebitsch. Completed in 1869, it was used as a guesthouse for some of Ismail Pasha's illustrious guests. Most had come to Egypt to attend the opening of the Suez Canal. Among its most noble guests were Emperor Franz-Josef of Austria and Empress Eugenie of France.

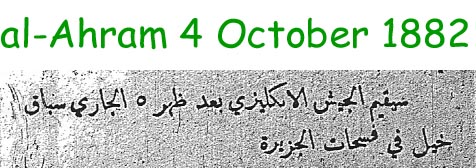

While no one knows the exact date when Gezira Sporting Club first opened, 1883 is a good guess for it was during that time that England consolidated its military hold over Egypt. This hypothesis is confirmed in several often contradictory notes from that period. One thing is however indisputable: the club was already a famous landmark by the close of last century as evidenced by guide books and turn-of-the-century literature. By then it was called the Khedivial Sporting Club (KSC) in honor of Khedive Mohammed Tewfik (r.1879-92). It was during his time and due to his largess that the Club was created for the benefit of the British land army and a growing army of British administrators.

Apart from Ismail's Gezira Palace and its 47 acres of gardens, the rest of the island was divided between the Vice-regal Daira (Khedivial estates) and the Roman Catholic Church. The latter's Mission to Central Africa, which operated under the protection of the Austrian Emperor, ran an agricultural and anti-slavery colony named after Pope Leo XIII. Its headquarter was located on the Island's northern sector (later referred to as "Northend" by the Anglo-Egyptians). In 1888, the Mission erected the Church of St. Joseph and an institute for missionaries and nuns.

Part of Gezira Sporting Club's 150 acres were carved out of the Khedivial Botanical Gardens, hence the acacias and jacarandas adorning the area. Once the land was formally leased to the British military command, club rules were chartered and the land demarcated into several recreational playing grounds.

At first, the club was for the use of the British Army of Occupation. "It is on Gezira polo grounds that the officers of the Cavalry Brigade are tested for military efficiency and fitness for command, and on Gezira tennis courts that examinations are held to decide as to the desirability or otherwise of retaining in the service the British officials of the Government," remarked a former British administrator in one of his recollections. He was evidently referring to peacetime England when inter-regimental wars were played out on polo fields.

What the pompous administrator forgot to add was that over the years the polo-playing cavalry brigades, whether at the Wellington Club in Bombay, the Calcutta Sporting Club or the Khedivial Sporting Club in Cairo, were prime attractions for British debutantes, especially those who coveted a husband with a position. These fair maidens braved it to the colonies and were nicknamed the "fishing fleet" for they tended to arrive en masse in Egypt or India during polo season. The debs who remained behind in England had to make do with left overs at either Hurlingham or Rowhampton.

With respect to these three elitist overseas clubs, the Khedivial Sporting Club, with its 365 days of sunshine, was the icing on the cake.

As British rank and file expanded in Egypt, it was thought civilians would enhance the Khedivial Sporting Club's recreational activities. The moving spirit behind the club's creation was a Captain Humphreys of the Mounted Infantry. Not only did he participate in the selection of the club grounds but he was also instrumental in the design of its first racecourse which had a 'distance' of a little over one mile. It was also on the club's racecourse that he passed away when, one morning, he was thrown off his horse in front of the main stand. The unlucky Humphreys landed right on the stone wall breaking his neck. Unable to move, he lay paralyzed at the same spot with a tent pitched over him until his family arrived from England. They were just in time to bid him farewell.

Heywood Walker Setton-Karr (1859-1938) of the Gordon Highlanders replaced Humphreys. He was the first in the long list of British secretaries which ended in the mid-1950s with Captain Eric Charles Pilley. Although Setton-Karr's position carried with it heavy responsibilities, it did not deter him from his other activities and pursuits which included the discovery of new emerald mines in Egypt's deserts.

On February 4, 1903, at the club's Extraordinary General Meeting chaired by the British Consul-General, Lord Cromer (referred to as al-Lord or al-ambashador by some Egyptians), it was agreed that the position of Club Secretary would no longer be a part-time occupation and that it would be open to candidates from outside the British officers class so that after the departure of Captain Alexander Harman, the then-sitting Honorary Secretary, a full-time administrator would be hired. The name of a Mr. H. Aspinall (of the Turf Club) was suggested at an annual salary of 200 pounds sterling.

According to Twentieth Century Impressions Of Egypt (Lloyds Publishing Company, London, 1909), the club's permanent Secretary and its Treasurer in 1911 were Keith H. Marsham and F.C. Bonham-Carter respectively; club membership was restricted to applicants elected by the committee on the recommendation of two members; and that army officers excluded, the roll numbered 750 members. It was also stated that the entrance fee was two Egyptian pounds. The various subscriptions were as follows: Life members, LE 50; resident members (married) LE 5, unmarried LE 3.6; country members (meaning those living outside a radius of 23 kilometers from the Cairo Post Office in Attaba Square), LE 2. Guests could visit the club whenever accompanied by those members by purchasing Day Passes for five piasters.

painted over countless times a surviving plaque evidences the metal fence surrounding GSC's perimiter was imported from the iron foundry of Francis Morton & Co. Ltd., Makers of Iron Buildings, located in Carston near Liverpool

Like the high-ranking officers corps, British civilian members were also taken in by the club's races. One of the first recorded races took place in 1885. The Starter was the Commanding Officer of the Egyptian Army otherwise known as the Sirdar, who at the time was General Frances Wallace Grenfell (1841-1925; afterwards 1st Baron of Kilvey). Grenfell had been present at the battle of Tel al-Kebir, which ended with the defeat of Orabi Pasha on September 13, 1882 and the start of the 72-year British military occupation of Egypt.

Another veteran Anglo-Egyptian was the Club's first steward General Charles Coles Pasha (1853-1926). It was Coles who remarked that "Egypt's climate made it possible to follow the races without recourse to binoculars, " and that the colors of the different jockeys were discernible even at a distance. Coles was however dissatisfied with the horses. "The European breeds, unlike the smaller Arabians, could not negotiate the course's sharp corners with comparable agility." It appears this problem was the focus of considerable debate during the club's early years.

While jockeys were imported without impediment from England, Arabian ponies had to be smuggled from Syria via al-Arish and Kantarah, Sinai, circumventing Turkish restrictions on their export into Egypt. The regular winner in these events was Hadeed, an Arabian pony belonging to the club's senior trainer, Mr. Langdon Rees. The runner up was another pony called Sir Hugh. Tired at being shown up again and again by the Arabian favorite, the Anglo-Egyptians clamored for the English mare Skittles, a competitor in the same weight and league. But first, Skittles had to be sent for from Malta. When the eventful day arrived, the mare won the day to the jubilation of the Britons whose pride had been piqued for some time now. It was a mournful native crowd that made its way to the Cairo mainland across the narrow Kasr al-Nil bridge.

By now the Cairo Derby was firmly established. The club's more popular races included the Khedivial Steeplechase, the Newmarket Stakes, the Jubilee Stakes, the Eclipse Stakes and the Koubbeh Handicap.

Betting at these races was based on an Indian lottery system introduced into Egypt by Coles Pasha just before he moved to Alexandria in 1899 where he assumed the position of Chief of Police and where he also founded the Alexandria Sporting Club.

Cole Pasha's system meant that the horse owner took one ticket and then claimed half. For other gamblers it was less favorable, for the prizes did not always compensate for blanks, and only a small percentage of the gains made it to the club's coffers.

Cole Pasha's unpopular lottery system was replaced by the pari-mutuel with all the profit going to the club. Although Egypt's racecourses were off limits to bookies, this did not stop the stakes and profits reaching stratospheric heights during WW1, a fact mostly attributed to the arrival of the Australian soldiers who proved to be fanatic gamblers.

The Winter Race Meetings which started in January was interrupted in March by the Gymkhana. Taking part in this annual sport and play event were the upper crust members of the British community arriving in their boaters and straw hats of all shapes and sizes armed with their eternal companion, the fly-swish. Edging between Cairo's society of mutual admirers and as if serving as an astute reminder this was still Africa were the turbaned Nubian sofragis balancing their silver platters of game pie, roast beef, ham chops and cucumber sandwiches. The dried-out, red-faced, sweaty English sire had his choice of sparkling champagne, Pimms or Campbells. Also present at these events, were the senior army officers, their horses and their wives (in that order), hence the Regimental Races, the Lloyd Lindsay, the Polo Race, the Green Howard Sweepstakes and the Horseback Musical Chairs.

Polo matches, of which ten or twelve were held in the course of the year, were the second most important social events after the races. In 1908-9 a "Challenge Cup" was added to the polo trophies courtesy of Seifallah Youssri Pasha whose name would be linked to the Gezira Club for the next forty years.

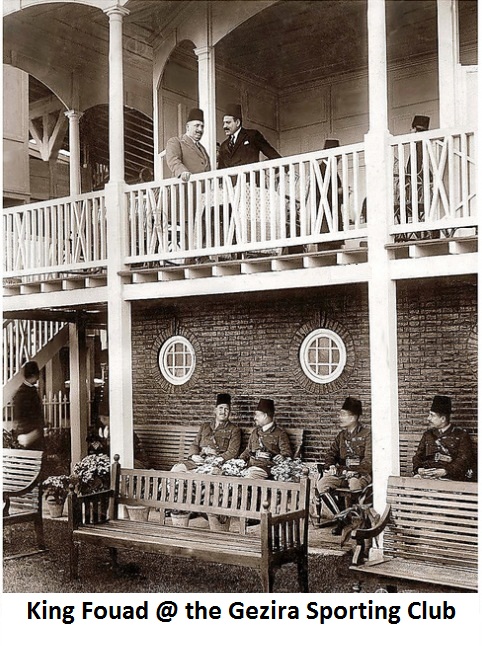

Youssri Pasha was one of the club's first Egyptian members and everyone will tell you he played polo on its fields with the Prince of Wales in June 1922. A club devotee, Youssri Pasha was nominated its first Egyptian Vice-President. When he died on its golf course on December 26, 1949, the sportsman-pasha had just turned 80.

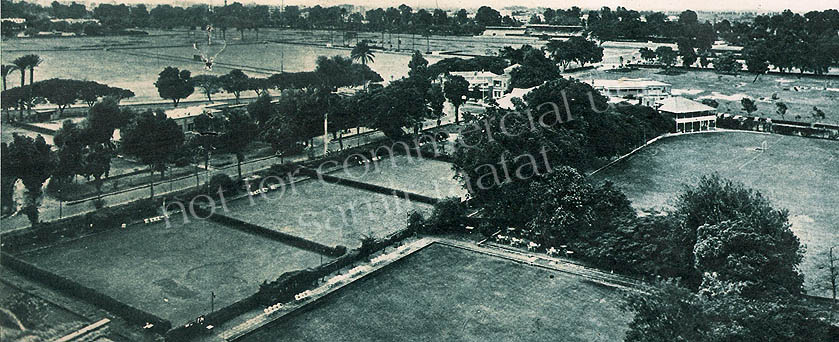

But lest anyone believe the club was a Shangri-La for whisky-drinking, polo-playing horse lovers, one must also mention its other popular amenities. In 1914, the Khedivial Sporting Club boasted a tea pavilion, four polo grounds, two racecourses, a 12-hole golf course, six squash racket courts, thirteen tennis grounds, and eight croquet lawns. The club's 750 British members were enjoying their finest colonial hours. Lording it at the top of this all-knowing community was the British Consul-General who by tradition was also the club's President.

Before he left Egypt for the last time on June 18, 1914, Consul-General Field-Marshal Lord Herbert Horatio Kitchener made two recommendations concerning the Khedivial Sporting Club, both of which with wasteful consequences.

Before he left Egypt for the last time on June 18, 1914, Consul-General Field-Marshal Lord Herbert Horatio Kitchener made two recommendations concerning the Khedivial Sporting Club, both of which with wasteful consequences.

Firstly, Egyptian members -- and they were few at the very most -- were to be barred from membership. No more natives.

Secondly, that the Khedive should be removed from the club's honorary patronage. What Kitchener actually meant by his latter recommendation was that Abbas Hilmi II should be removed from Egypt's throne altogether. Kitchener's disdain for his former employer had been public knowledge prompting his recurrent recommendations that the pro-Germanic Khedive be replaced by someone more agreeable to British interests.

Shortly after Kitchener became his country's War Minister in 1914, a volunteer reserve unit was formed from amongst Gezira Club's able-bodied members including the 50 year old Bimbashi (officer) Joseph McPherson, author of that now-famous book The Man Who Liked Egypt (BBC Ariel Books, 1983). It would be thanks to Kitchener's recommendation that the unit, which called itself Pharaoh's Foot, had an all-British character, for by now there were no more "foreigners" or "Gyppies" left in the club.

Kitchener's second recommendation was realized on December 20, 1914 when the complying Khedive's uncle was forcibly placed on the throne of Egypt with the new title of Sultan. With the last of the Khedives gone, it was time to find a new name for that great swathe of parkland heretofore known as the Khedivial Sporting Club.

From a semi-autonomous Ottoman viceroyalty, Egypt had become a British Protectorate so that the club's Anglo-Egyptian squatters were now the country's real masters. Had he foretold Egypt's fate, Lord Cromer, in his capacity as the club's president in 1902, would have dispensed with his efforts to establish freehold ownership of the club by virtue of a 20-year squatters’ right. The proconsul's claim in that direction had been contested by the usually compliant Egyptian Government. In a conciliatory gesture to al-Lord, the land was instead leased to the club at a nominal rent for a period of 66 years ending in 1966.

BEFORE 1952

Between the two World Wars, Cairo, Alexandria, the Canal towns of Port Said, Ismailia and Suez, were cosmopolitan havens with large, influential communities living side by side carrying on as though the world was their own United Nations. There were the Greeks, the Italians, the Jews, the Syrians (includes Lebanese and Jerusalemites), the Armenians, and in much smaller numbers the British and the French whose cultural and social clout extended across all the other communities. Each community had its own place of worship, its own hospitals and retirement homes, its elected president and board and its own social and sports clubs. Cross-over mixing between communities occurred only at the very top where education and worldly culture were unifying factors. One of the most popular meeting places for those polished ladies and gentlemen of Egypt's cosmo-monde was the Gezira Sporting Club.

The Gezira Sporting Club's apartheid (Britons Only!) membership crisis was resolved when a trickle of Egyptians was allowed back in Gezira Sporting Club after WW1. They were either related to the reigning sultan or members of the Western-educated gentry. To discourage the other Egyptian wanabees the trickle was subjected to a convoluted quota and vetting system. Even star polo player Victor Mansour Semeika, the son of Wassef Semeika Pasha, Egypt's former Coptic Minister of Communication, waited several years before he was invited to join in 1933. Other less fortunate Egyptians visited as guests of British members. A classic example is how Kadria Foda, the daughter of a Cairene notable (now Grande dame of Egyptian society), made it inside the Gezira Club courtesy of Miss King her British governess. And whenever Kadria and her sisters ran into one or the other Egyptian families on the club grounds, the first furtive query was, "How did you make it in, have you become members?!"

General Monty of Alamein fame watching a tennis final at Gezira Sporting Club

members horse cavalry at Gezira Sporting Club in 1951

L-R: Polo Cpt. Saleh Foda, Princess Khadiga Hassan, Kamal S Faizi, Kadria Zaki, Galal S Faizi, Kamel Wassef

Forefront: Abdallah Gazayerli, Hassan El Sawi

What had started as a British military club evolved into one of Egypt's greatest outdoor attractions. Over the next five decades Gezira Sporting Club remained a landmark institution and one of Cairo's greatest assets. Constant improvements and extensions at the Gezira rendered its sports and social facilities second to none except perhaps Buenos Aires' Jockey Club and the Wellington of Bombay.

In time for the 1929 Christmas dance a new LE 5,500 dining building with a verandah facing the cricket pitch was inaugurated. The firm D.C.M. Brooks was commended for completing the construction in record time thus avoiding a daily LE 5 delay penalty.

The new premises' oak parquet made an excellent dancing floor and meals could now be served throughout the year. Above the dinner lounge was an assembly room with a center well looking down on the hall below. It is from there that pretty maidens and wallflowers watched the ball dances without too much embarrassment. Tea was served and family bridge played on the new building's upper floor. Despite its apparent advantages, there were quite a few members who had been against the project especially when it meant sacrificing what used to be the old ladies rooms, the old squash courts and the secretary's office. Moreover, several palm trees, the old cricket pavilion plus two croquet lawns also had to go.

Black tie celebrations for the new acquisition were hardly over when another part of the club met with unexpected disaster. In May 1930, fire broke out destroying the quintessential polo stand. The club's mowing machines, responsible for the excellent year-round maintenance of the greens, were also decimated. While the stands were insured, the machines were not and LE 500 had to be raised post haste. The club ladies got together and a successful fund-raiser bazaar was held. When it was time for the 1930-31 polo season, all was back in place and the season's nine tournaments were played out according to schedule. With Count Nakko on hand to partake in the Visitor's Cup, the season's launcher, that year's polo turned out to be an exceptional one.

polo season at Gezira 1950; Polo player Wahid Yussri Pasha with friends at Lido

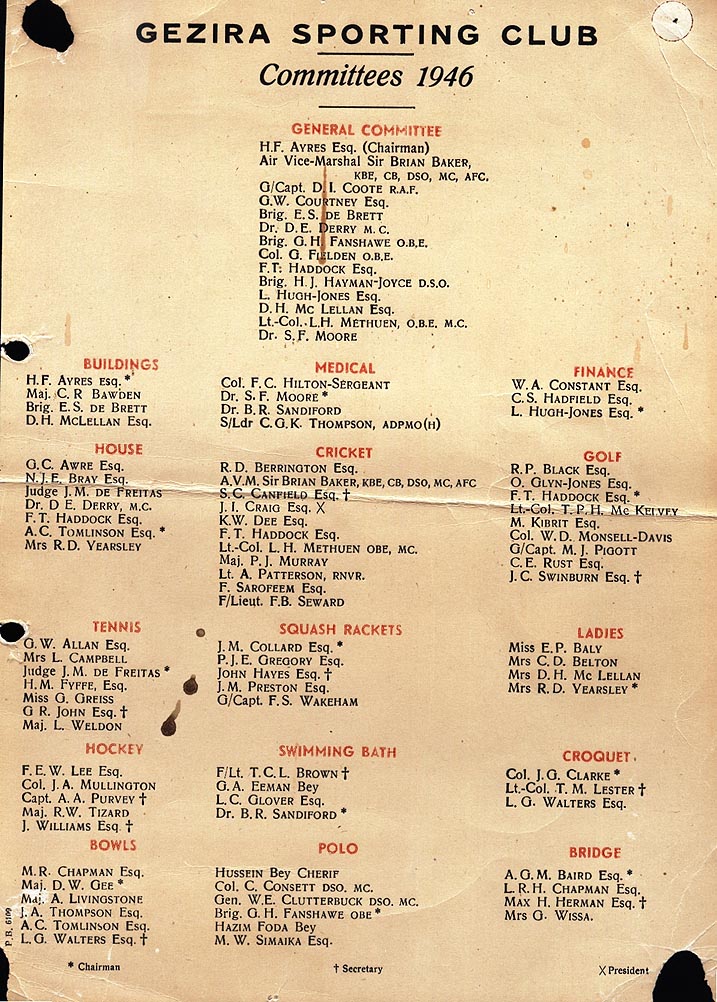

above item courtesy of Wael Hazem Foda; note that only 5 committee members are Egyptian: 3 Copts and 2 Muslims

Like polo, the Gezira Sporting Club races were also on the international social calendar. Between 1927 and 1947 an average profit of LE 7,600 per annum was paid into the club's reserves from racing alone. In 1948, it was decided that the time had come to renovate this lucrative facility which consisted of three separate stands: the King's Stand, the Grand Stand and the Public Stand. At the club's Extraordinary General Assembly of March 1949, a motion was approved to build a new all-encompassing concrete stand at a cost of LE 50,000. In November of the same year, the bleachers were inaugurated thereby doubling the seating capacity to 1,000 spectators.

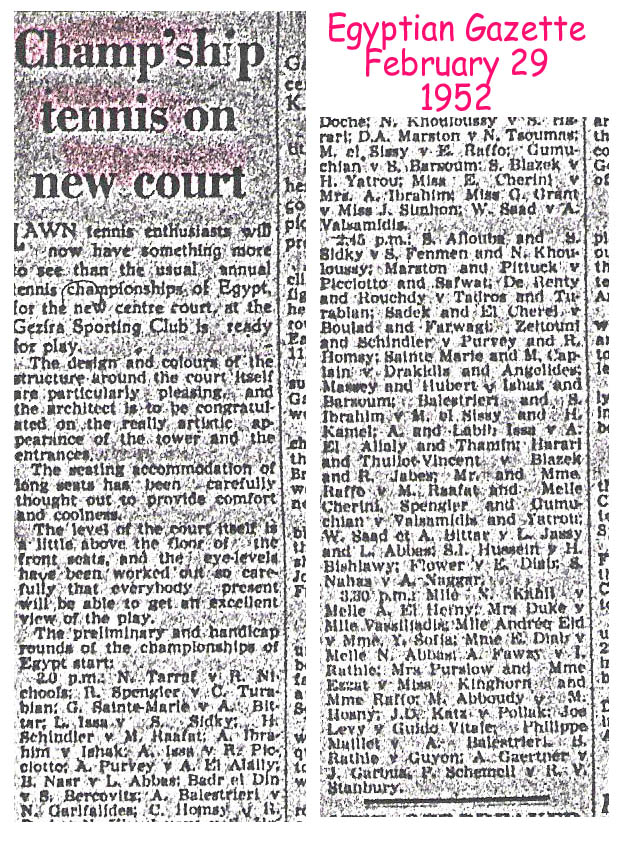

Ever since 1907, Gezira Sporting Club was the official home of Egypt's lawn tennis with open tournaments and championships held on its clay courts at regular intervals. As of 1925, international celebrities took part in these widely attended events. Despite, the launch of the Egyptian Lawn Tennis Association (LTA) Championship in 1934, Gezira Sporting Club continued to offer its two cups: the Doherty which was, awarded to the winners of the singles, and the Slazenger for the doubles. Until 1929, the former was the preserve of Auguste Zerlendi, an Alexandria Greek who made tennis history. Another Doherty Cup contender was Sir Cecil Campbell, Marconi's representative in Egypt. The early 1930s saw the arrival of "Joujou" and "Pierrot" Grandguillot who made it to the finals only to be replaced later in the decade, by Gezira Sporting Club favorites, René Dukich, André Najar and Mahmoud Talaat.

It would take a world war to interrupt tennis season at the Gezira Sporting Club. Moreover, plans for a new LE 40,000 center court were deferred to March 1952 at which time Rolando Del Bello crushed Egypt's Marcel Cohen during that year's International Tennis Championship.

It was this same center court that hosted shortly after Egypt's first ever "Holiday on Ice" show, and in July 1954, was transformed into a corrida to accommodate Egypt's first and last ever bull fight. But before Mickey Mouse and matadors appeared at Gezira Sporting Club, there were the thousands of Allied military who invaded it during WW2.

During the Second World War, Gezira Sporting Club brimmed with British military personnel many of whom lived in Zamalek. The more privileged among them occupied villas and apartments overlooking the club. The polo fields and the surrounding flora was a welcome sight especially the firs from Aberdeen, the azaleas from Sussex Gardens, and the beds of lavender from London. At his window, listening to the self moans of doves outside, Lord Moyne, the former Leader of the House of Lords, could feast his eyes upon a corner of England itself." (The Deed by Gerald Frank, Simon & Schuster, N.Y.).

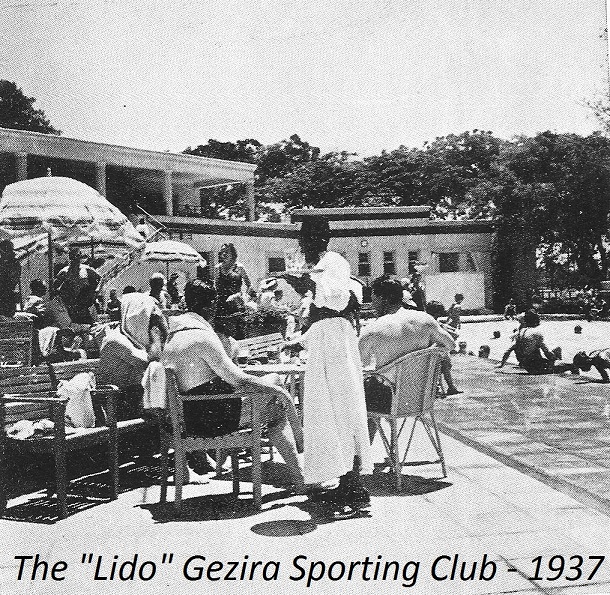

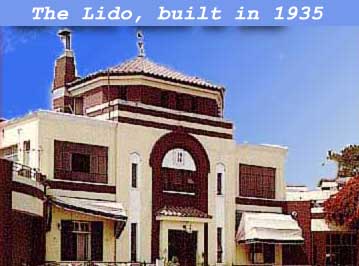

Except for special occasions, privates, and anyone else below the rank of officer, were not allowed on Gezira Sporting Club grounds during the war. There were enough officers as it was to fill the place. With so many eligible uniforms the wizened maidens from Cairo's large Anglophile crowd were forever hanging out at the newly built Lido in search for an M.R.S. Degree in Family Relations. Many succeeded with flying British colors. Every other day the newspapers announced this of that engagement. Not surprising then that Misses Lucette Sapriel, Denise Harari, Mimi Wissa and Yvette Zarb, became Mrs. Makepeace, Mrs. Guysales, Mrs. Spider and Lady Toplofty.

TWEAK THE LION BY THE TAIL

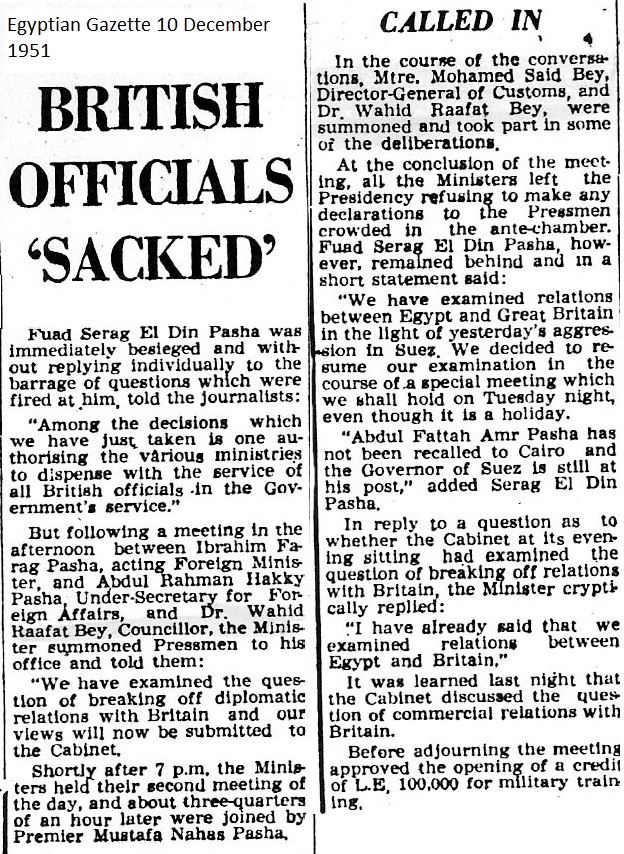

DECEMBER 9, 1951: Deadlock between Egypt and Britain over the Sudan question and the presence of over 54,000 unwelcome British Forces holed up in the Canal Zone. The popular-bourgeois Wafdist government of the day received daily accounts describing how the heavily armed British "Tommy" incited unarmed Egyptian civilians in the Suez Canal Zone. Reports of casualties on both sides were on the rise in the towns of Ismailia and Suez. During a tumultuous three-hour parley presided over by Moustafa al-Nahhas, the Egyptian Cabinet reviewed its standpoint vis-à-vis the intransigent and short-sighted view adopted by its British counterpart. Options ranged from severing relations with London and nationalizing the Suez Canal, to signing a non-aggression pact with Russia "which knew how to stand up to Britain." The fiery prime minister had to act quickly or risk losing credibility. Extremist factions within the angry populace were becoming more bellicose by the hour. They could not comprehend Britain's obstinacy over relinquishing its 70-year hold on Egypt.

In the evening, a temporary solution was reached. Tweak the doddering lion by the tail. And the British lion's wearied tail was just across the Nile on Gezira Island.

Following the historic cabinet meeting, Minister of Interior, Fouad Serag al-Din Pasha, tersely announced that Gezira Sporting Club (GSC) would be taken over "for public utility purposes and for the construction of the projected Mohammed Ali stadium." In other words, the last British bastion of propriety and respectability in the region was to be Egyptianized. Moreover, all remaining British officials serving in universities, government schools, the ministry of public works and the Egyptian State Railways were hereby dismissed.

On that day, the 2,453 strong membership of the club was divided into 743 Britons, 594 foreigners -- many of them were more British then the British themselves -- and 1,116 Egyptians. The latter were from society's top drawer having made it past the condescending vetting committee. Some of these privileged folks thought that appending the "GSC" membership next to their name in the Who's Who was tantamount to receiving an OBE.

Even though Egyptians made up the majority of the club's membership, the picture was very different inside the Boardroom where Britons were still in control prompting the French ambassador to exclaim "les Anglais sont toujours chez eux!" Yet, the future Prime Minister of France, Monsieur Couve du Murville, couldn't have been more mistaken. Little did he realize how the imminent events were going to bring down the worn-out British Empire flat on its face.

JANUARY 12, 1952. "Gezira Sporting Club Races Canceled During Week-end" read the morning's headlines. As far as anyone could remember, only World War I had suspended the races at the club! Why, up until the previous day it was polo as usual with a gripping match pitting the home team comprising Saleh Foda, EricTyrell-Martin, Mohammed Lamloum and Victor Mansour Semeika against the Crescents. The home team won 12/7.

JANUARY 12, 1952. "Gezira Sporting Club Races Canceled During Week-end" read the morning's headlines. As far as anyone could remember, only World War I had suspended the races at the club! Why, up until the previous day it was polo as usual with a gripping match pitting the home team comprising Saleh Foda, EricTyrell-Martin, Mohammed Lamloum and Victor Mansour Semeika against the Crescents. The home team won 12/7.

JANUARY 12 bis. The wheels of Egyptianization start to roll. The Club's Egyptian Vice President, Sherif Sabri Pasha (the king's uncle) calls on the Governorate to discuss expropriation and compensation measures! The incredulous Britons, starting with their ambassador, are aghast. The British Embassy in Kasr al-Dubara where the portraits of so many of the club's former presidents still hang, burns the midnight oil.

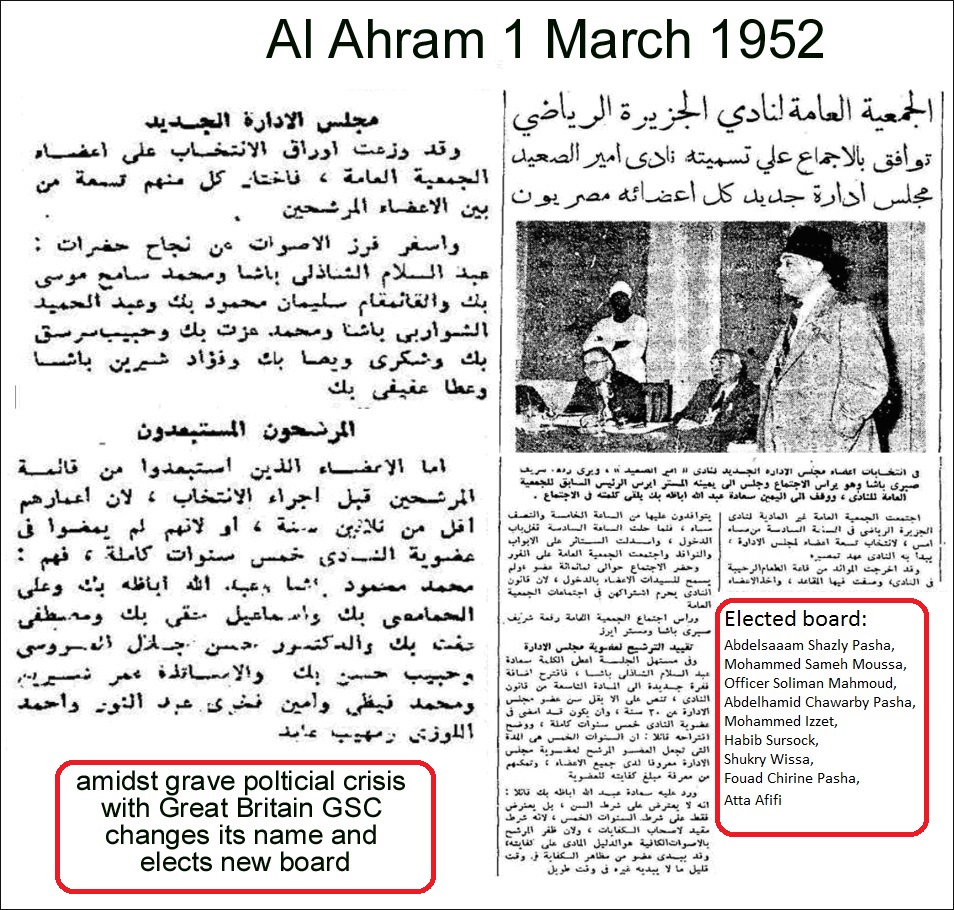

JANUARY 24. At the club's General Assembly, it is announced that Britain's Ambassador, Sir Ralph Skrine Stevenson, resigned from the Presidency. Sir Thomas Russell Pasha, the former Chief of Cairo Police and the club's Vice President, tenders their resignation along with the rest of the General Committee, consisting of its Chairman Henry Francis, and Messrs. James S. Coxon, Walter Arthur Constant, Joseph P. Sheridan, Colonel P. C. Lord, Colonel Thomas M. Moore, Seifallah Khairy Bey, Abdelsalaam al-Shazly Pasha, Mohammed Sultan Pasha and Soliman Naguib Bey. Former cricket champion R. Etches also steps down, thus vacating his sinecure post of Acting-Secretary, which he had occupied since 1928.

An extraordinary General Assembly is scheduled for February 8, at which time a new committee will be elected. According to another related press release, these measures were "taken to ensure the continuation of the club in accordance of the new circumstances aiming at Egyptianizing it".

JANUARY 26 OR BLACK SATURDAY. Zamalek is a ghost island. Instead of preparing for one of her well-attended aprés-polo soirées, Cairo socialite Kadria Foda watches in disbelief from the safety of the Marespini Building on Gezira Street as downtown Cairo goes up in flames. Foreigners perish in the Turf Club fire while other British properties are torched by an unruly mob. Across from Foda's apartment stands an abandoned Gezira Sporting Club. It was as though Cairo's great green lung had stopped breathing. Had its Egyptianization been delayed by a few days, perhaps it too would have gone up in smoke.

But on the other hand, the self-important inglizis and their self-serving toffee-nosed committees were gone at last. No more Empire Day celebrations and [British] coronation dances. No more parades and searchlight tattoos on the club's polo grounds with poppies raining from the skies. Also gone were these wartime parties for two or three thousand British soldiers at a time with tea served by Jacqueline Lampson. No more provocative sounds of 'God Save the King' each time Jacqueline's husband, Sir Miles, heaved into his box at the races dressed in his grey frock-coat and ludicrous topper.

The days of Newmarket stakes had ended. Even the hedayas or kites seemed intoxicated for they too remembered how the avaricious English ambashador had found perverted pleasure at shooting them down because they mistook his golf balls for eggs! "Ma'a alf salama ya Khawaga Lambson" they seemed to cry as they circled far above in the club's blue sky.

FEBRUARY 29. On that leap-year day, a new Gezira Sporting Club Board of Egyptian pashas and beys is duly elected. A down-sized Captain Eric C. Pilley is asked to stay on as Club Secretary until someone suitable is found. As it turned out the Telly Savallas look-alike Secretary remained another four years.

The Gezira Sporting Club had reached a turning point and it was now open season for the new administration to assert itself and to purge what remained of the British legacy.

One of the new Board's first resolutions was to change the club's name to NASR. The acronym stood for Nadi Amir al-Sa'id al-Riadi honoring the six-week-old heir to the throne whose official title was Prince of Sa'id (Upper Egypt). Even during the tottering monarchy's last days, fawning courtiers and obliging notables were not lacking. Only this particular bunch was unaware their titles and privileges had a few more months to go before it all came tumbling down around them. (One positive outcome from the fall of the monarchy was for the club to retake its old name.)

1955. Former Egyptian Ambassador to Washington abruptly resigns from the club's presidency. An upright gentleman, he refused to concur the government's decision to expropriate several feddans of the club grounds, entailing the amputation of nine holes from the world-famous golf course. Little did the ambassador know that this was the first in a series of land grabs which over the years would decimate the Gezira Club grounds.

The resigning senior diplomat was promptly replaced by an officer. As though mirroring what was taking place in the rest of Egypt, the club's civilian administration was replaced by a military version, an action that in many ways brought the club back to where it all began when the [British] military brass ran the show.

Another chapter in Gezira Sporting Club's history was about to unfold.

FORTY YEARS LATER. 1995. Kadria Foda still at No. 14 Gezira street (ex-Marespini Bldg) watches as several surviving palms and other decorative trees are bulldozed at the Gezira Sporting Club to make way for new collateral facilities. Cairo's great outdoors is rapidly vanishing. Egypt’s population quadrupled in four decades! The capital’s exhausted lungs are collapsing. Increasingly, Cairo’s skyline is silouhetted against a dark, polluted pall evoking January 1952's Black Saturday, that fateful turning point in Egypt's recent history, a milestone that was supposedly going to drain the colonial swamps undoing the wrongs of the past and turn this region into a better one...

Post-centennial chairmen of the board: 1982 - 2015

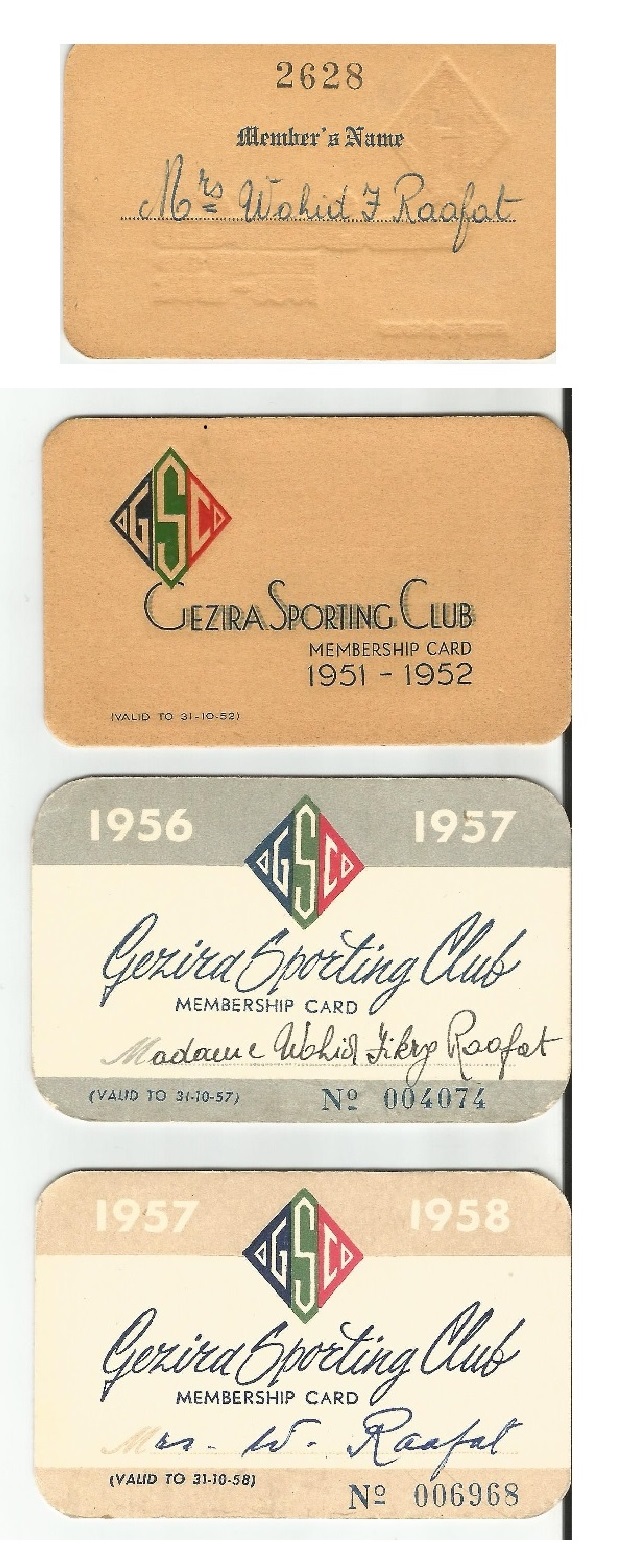

membership cards

|

|

|

|