|

|

|

|

|

Cheers to our "talented" literature prize awardee. Your pain his gain !!!

|

|

|

EGY.COM - ZAMALEK

|

|

|

|

|

Cairo Times, 6 January 2000 |

The baroque-ish mansion overlooking the Nile at No.15 Mohammed Mazhar Street, Zamalek, is touted as an 'educational library.' Millions were spent to restore, staff and computerize the Greater Cairo Library. Once the hubbub had settled after the library's 1995 inauguration, I decided to go to see the results for myself.

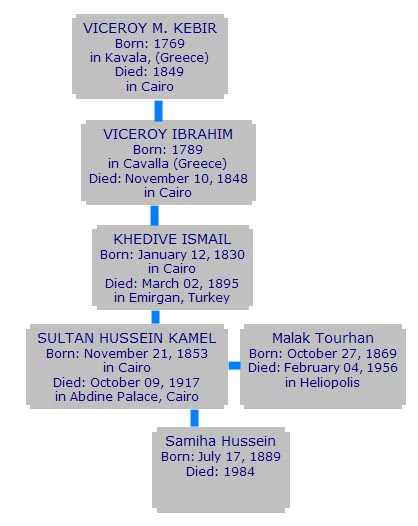

That the outside of the building looked impressive came as no surprise. The library is domiciled in the former palace of a daughter of Sultan Hussein Kamel who ruled Egypt between 1914 and 1917. The surprise came inside. How could such sluggishness prevail in what is supposedly a center of learning and information?

Time and again, the library director appeared in the media explaining the collection's forte: the Greater Cairo Library is the single largest repository of information regarding Umm Al Dunya. Every conceivable book, map, document, survey plan and statistic regarding Cairo's history, geography and character is available to the public free of charge. And using the latest technology--meaning the Internet--you could tap mines of information on the library's website. Or so he said.

Here's a sample of what I found. To begin with, no one at the library could come up with information regarding the library building, beyond that it had been the palace of Princess Samiha, daughter of Sultan Hussein. But could anyone tell me when it was built, the name of the architect, or about any important event that had taken place on the premises of this Zamalek landmark?

No.

How about something about the princess or, better still, about Mr. Mohammed Mazhar, after whom the street on which the library stands is named? Blank. Where could I get such information?

Abyss.

Tapping into the library's pathetic website was equally embarrassing. Although the site echoes much of what the director has said on national television, names of certain books that I know are on the library shelves failed to appear on the web database. For instance, "Cairo: The City Victorious," which was recently reviewed the world over, is not listed; neither, for that matter, is its author. Ditto for so many other books on Cairo.

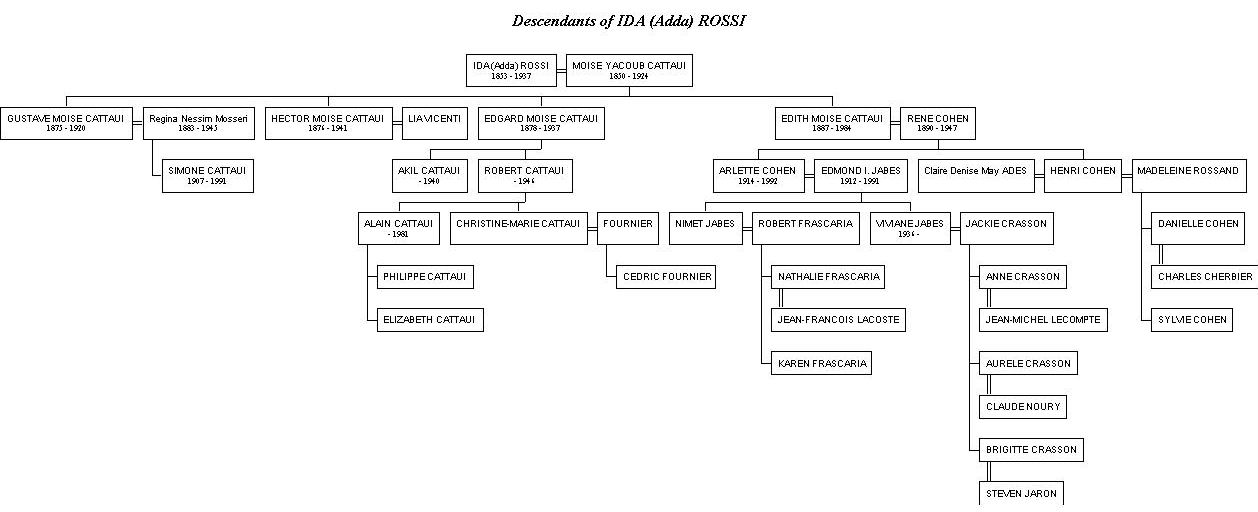

And yet last year, on French television, a literary talk show took the time to discuss a recently published book about the Egyptian-born poet Edmond Jabes. The 300-page work discusses the poet's early years in school, his agitated youth in Cairo and his formative years working as a broker at the Cairo bourse. All this is set against a backdrop of a cosmopolitan city where multilingual intellectual salons were an everyday affair. The book walks us through the poet's first encounter with his future wife, and their subsequent marriage, which took place in 1935 at her family homestead, No. 15 Mohammed Mazhar Street (ex-Rue Doctor Rossi).

French television told us what is absent from the library's definitive brochure and what's still wanting in the minds of its employees: that the original occupants of the Greater Cairo Library were the Cattauis, who moved to Zamalek from downtown Cairo after the family patriarch, Moussa (aka. Moise de Cattaui) Pasha, died in 1924.

It was Moussa Pasha's granddaughter Arlette who married Jabes. Maadi resident Vera Bajocchi, now 90-something, recalls the occasion. "This was one of the few times I visited my rich relatives' house. We nicknamed the house 'the Wedding Cake' because of its external appearance."

Jabes was not the only poet to grace the villa. According to those who knew her well, Princess Samiha who had purchased the house in 1942, was herself an accomplished poet although none of her works were ever published. Born in 1889 and married three times, she led a tumultuous life by court standards one of her many attributes being that of an excellent markswoman her house abounding with priceless guns and trophy game animals; many of them having been shot by her third husband Wahid Yussri.

Having outlived most of her generation and unable to survive on her meager state allowance the former princess was condemned to absolute anonymity which is perhaps why she clandestinely sold some of the house furniture surviving on the proceeds. Neighbors, seeing the what they assumed was a homeless lady walking down Mohammed Mazhar Street, would attempt to give her a little charity. Little did they know that she was a sultan's daughter--or that shortly after she died at age 100, her house would become the nation's leading center for the study of its capital city.

Sometimes ignorance is indeed bliss.

For detailed family tree of Viceroy Mohammed Ali dynasty click here

|

|

|

|