THE BOUTROS GHALI WE DON'T ALL KNOW

by Samir Raafat

The Jordan Star, September 26, 1996; Middle East Times, September 29, 1996

|

|

|

|

|

|

EGY.COM - PERSONALITIES

|

|

UNIVERSITY PROFESSOR

I knew the man simply as 'ya doktor' which is how we addressed the incumbent Sec-Gen of the United Nations when he taught international law during my Freshman year at Cairo University. These were the '60s and Professor Ghali's mission was to acquaint us on the perplexities of political science. Yet, as far as I recall, his no-show record surpassed that of his most wayward student. We were ostensibly told 'al doktor' had other engagements so that more often than not his teaching assignments were delegated to a 'mo'eid'--assistant lecturer.

Whatever the reasons for his absence, we never doubted their merit. Faculty remuneration in those days were modest and Dr. Ghali whose attendance record was nonetheless better than most, had other professional interests. Yet, whenever we saw his Fiat coupé parked adjacent to the college building, we knew we could look forward to an absorbing two-hour lecture.

Behind his back we had several nicknames for him. Graduates from English language schools referred to him as "Peter Precious," an obvious play on his name --Boutros being the Arabic version for Peter, and precious is the English translation of Ghali. Colleagues from French language schools including the fabled Jesuits where Professor Ghali had studied as a schoolboy, referred to him simply as "Bo-bo" a nickname that would resurface at the UN years later.

My father, sixteen years the Sec-Gen's senior, read law to Ghali's generation at Cairo University. He knew Professor Ghali simply as 'Dr. Boutros' which is how the Sec-Gen's contemporaries addressed him even when he became Minister of State in 1977. And whenever Ghali signed his scholarly articles in 'al-Seyassa al-Dawlia,' a worthwhile magazine he helped produce, he did so as 'Dr. Boutros Ghali.'

Seldom did one see the double-barreled appellation which became so fashionable after Boutros 'Boutros-Ghali' made it to the United Nations in January 1992.

BOUTROS GHALI THE FIRST (1846-1910)

The first Boutros Ghali was the UN Sec-Gen's grandfather --not his father or uncle as many mistakenly believe.

The first Boutros Ghali was the UN Sec-Gen's grandfather --not his father or uncle as many mistakenly believe.

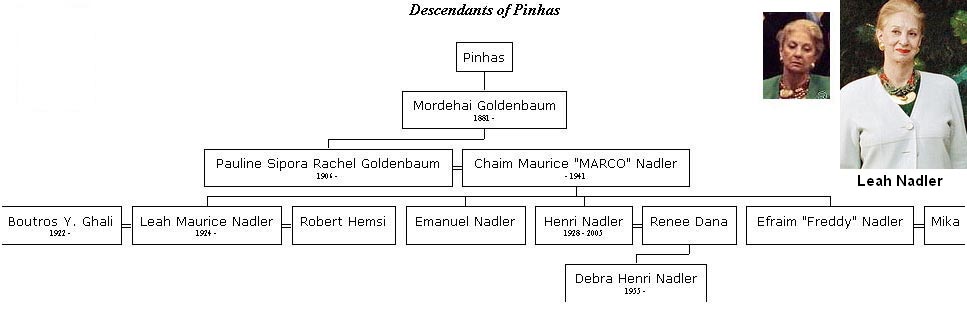

The Sec-Gen's father was called Youssef, a self-effaced member of the landed gentry who as tradition warrants, married Sophie Sharobim, a member of his own Coptic background. From her he had three sons: Boutros, Michel and Raouf. Unlike their father and grandfather, the sons married (re-married in the case of Boutros and Raouf) outside their denomination, their present respective wives being Jewish (Leah Nadler), Moslem (Wafika Shiaty) and Lutheran (Brit from Norway).

In keeping with tradition Youssef and Sophie's eldest son was named after his eminent paternal grandfather Boutros Ghali Pasha who departed so unexpectedly in 1910.

Although Boutros Ghali Pasha is written up in history as the only Copt ever to occupy the post of Prime Minister, there was another one --Youssef Wahba Pasha who, for a very brief period, headed a purported Council of Ministers during the British Protectorate in 1919/20.

Aside from his high office, another singular event which earned Ghali Pasha a place in the Egyptian hall of fame, was that he was one of three Egyptian premiers assassinated this century. The others, Ahmed Maher Pasha and Mahmoud Fahmi al-Nokrashi Pasha, were slain in 1945 and 1948 respectively.

The British being Egypt's de facto rulers up until 1922 meant that the khedive to whom Ghali Pasha swore allegiance (first as foreign minister and later as head of government) was little else than reluctant pawn of British imperialism. His government was effective only within the limits ascribed to it by the British Consul-General.

Under these circumstances, 'Egypt for Egyptians' was the rallying cry of local nationalist movements. Similarly, there was a growing rationale calling for the prime minister to belong to the majority faith. In other words, Ghali Pasha's fate was pre-ordained even before he was gunned down on February 20, 1910 by Ibrahim Nassif al-Wardani, a young pharmacologist graduate freshly returned from the UK.

The cries heard in the street following the pasha's assassination summed up the general mood: "al-Wardani atal al Nosrani."

Historians will argue that the reference to al-Nosrani--the Nazarene--had more to do with the late pasha's pro-British leanings than his being a Copt. Nevertheless, the imposition of a Coptic prime minister had an ill-boding effect on a predominantly Moslem nation whose educated elite clamored for an independent Egypt. It was all right that the country had thrice been handled by a Christian Armenian prime minister --Nubar Nubarian-- but things had changed drastically since the days of the enlightened Khedive Ismail..

The first Boutros Ghali came from Upper Egypt where his father Nairouz oversaw the Daira estates of Khedive Ismail's brother. His formative school years were spent in a college founded by the Coptic Patriarch Cyril IV. Later, in public life, Ghali Pasha would be perceived as siding with pro-English elements within Egyptian society. Perhaps it also had to do with the fact that he had served under the long-time Prime Minister Moustafa Fahmy Pasha, a man the British considered "too English, not sufficiently Egyptian." The stigma had invariably rubbed off on his Coptic collaborator.

The partiality of Ghali Pasha for Egypt's British rulers and his disposition to please them was reportedly in evidence during the June 1906 Dinshway trial. The Egyptian defendants had tussled with British officers who mistakenly shot the wife of a village elder while pigeon-shooting. As a result they were sent to the gallows. It was Ghali Pasha, who as interim Minister of Justice had concurred the ignominious verdicts. By so doing he had in fact signed his own death warrant.

Neither had Egypt's nationalists forgiven the pasha his close identification with the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium Agreement with the Sudan in 1899. Nor his recommendation for the promulgation of a 40 year concession of the Suez Canal in favor of its foreign shareholders.

1910. in occupation Christian the of nominee assassination was deeds, perceived ill pasha?s result end combined The>After WW-I nationalist agitation was ready to explode. The Wafd Party--the self-declared enemy of religious fanaticism--was formed from amongst the leading Coptic and Moslem notables of the country. A Ghali from the second generation which unlike the first had become ever so Francophile, was a pillar of the new anti-British party. The much respected Wassif Ghali Pasha (son of the first Boutros Ghali and uncle of the second) held the foreign affairs portfolio in each of the Wafd governments of 1924, 1928, 1930 and 1937.

It was in Wassif Ghali's understated riverfront house in Giza that some of the Wafd's historic meetings took place. And it was there that Mustafa al-Nahas was upheld by the party elders following the death of Saad Zaghloul Pasha, Egypt's canonized and popular leader of the 1920s.

BOUTROS GHALI THE SECOND (b. Nov. 14, 1922)

Four decades would pass before another Ghali took over the helm of Egypt's Foreign Affairs. But this time it was a sudden turn of events which led Dr. Boutros Ghali to follow in his grandfather and uncle's public office footsteps.

Four decades would pass before another Ghali took over the helm of Egypt's Foreign Affairs. But this time it was a sudden turn of events which led Dr. Boutros Ghali to follow in his grandfather and uncle's public office footsteps.

Fate had it that Boutros Boutros-Ghali would walk into the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on 17 November 1977, a few hours after Egypt's then-chief of diplomacy Ismail Fahmy, along with his second in command Mohammed Mahmoud Riad, resigned over Sadat's Jerusalem initiative. Suddenly and unexpectedly the two first slots at foreign affairs were unexpectedly vacant.

Unlike the Wafd days, the Number One slot could no longer be allocated to a Copt, especially now that Egypt was heeded as the leader of both the Arab and Islamic worlds. Dr. Ghali would therefore make do with the subordinate rank of minister of state for foreign affairs. In fact, on 25 December 1977, the position of chief of diplomacy went to Ibrahim Kamel, a Sadat crony from the old days. Kamel would however resign in September 1978 in protest of the Camp David negotiations so that once more the position remained vacant. On 17 February 1979, a presidential decree awarded the post to the then-Prime Minister Dr. Moustafa Khalil.

Boutros Boutros-Ghali would serve under Khalil and three of his successors: General Kamal Hassan Ali (1980-84), Dr. Esmat Abdel Meguid (1984-91) and the much younger Amr Moussa. The latter's arrival meant Ghali's days at Foreign Affairs were numbered. Efforts for his obtaining the UN's chief position went into full gear.

IL FAUT PLAIRE AUX SOUVERAINS

It was as minister without portfolio that Ghali accompanied Anwar Sadat on his historic trip to both Israel and to the divided city of Jerusalem where Sadat prayed in the Aqsa Mosque.

It was as minister without portfolio that Ghali accompanied Anwar Sadat on his historic trip to both Israel and to the divided city of Jerusalem where Sadat prayed in the Aqsa Mosque.

The Holy City was special to Ghali for a variety of reasons. Firstly, it was the disputed capital of both Israel and Palestine making it the most talked about pre-biblical city in the world. Secondly, Jerusalem had amongst its religious institutions the important and disputed Coptic monastery of Deir al-Sultan. Thirdly, Jerusalem happens to be the city of birth of Ghali's sympathetic mother-in-law, Pauline Sipora Rachel Goldenbaum of whom very little is known outside the Ghali menage. However it appears that in March 1923, at the young age of 17, Pauline tied the knot in Alexandria with Chaim Maurice Hirsch-Nadler who became the city's leading candy manufacturer. Whereas the Nadlers were immigrant Jews from Eastern Europe, Mordechai Pinhas, Ghali's grandfather-in-law, was born in Safed, Palestine in 1881 where he became an important rabbi.

Most definitely, Ghali's visit to Jerusalem would constitute an important milestone in his career.

It was after Sadat's cabal to Jerusalem that Ghali would make it to the forefront of the national and international political scene. Yet, forever cautious, he seemed to stick to his old maxim: "il faut plaire aux souverains" which, in English, could be interpreted as 'one must occasionally stoop to conquer.'

I remembered then how during my first year in college, Professor Ghali's lectures on political systems hardly ever touched upon Egypt's. The learned professor of international law went to great pains never to appear as though he were taking sides. He went the extra mile not to criticize Nasser's regime. Yet in those days everyone on campus did little else. After the humiliating defeat during the Six Day War of 1967 university professors of all creeds--communists, Nasserists and socialists-- openly criticized the government. But not professor Ghali.

That year college campuses erupted in Cairo and thousands of demonstrating students marched angrily to the rubber stamp parliament near Lazoghly Square. And while stirring debates took place under the parliamentary rotunda, across the Nile, in Cairo University's lecture halls, Professor Ghali stuck firmly to his academic notes never uttering anything that could compromise him. "Peter Precious" had become "Peter Cautious." His 'il faut plaire aux souverains' disposition was increasingly palpable.

Was Ghali's scrupulous behavior due to some minority complex, we would occasionally ask ourselves.

Either out of ignorance or simply because we were in our Freshman year, we ignored the fact that we were privileged observers of a modern adaptation to Talleyrand-nism.

Talleyrand, we later learned from Professor Ghali, was the cunning prince of the church turned senior French diplomat and self-perceived womanizer. He had adroitly maneuvered his way through the turbulent Directoire years, the expansionist Napoleonic era and the blustery Bourbon comeback. With each change of regime, the compliant French diplomat always came back on top.

OVER THE TOP

OVER THE TOP

When he made it to the top position at the UN, Ghali became a household word and a prime time denizen. This is not to say that he was heretofore an unknown somebody. Quite the contrary. Ghali had become a popular figure in both the dictator-infested African continent and the countries of the Francophony. His frequent-flying habits took him to the darkest corners of Africa always by way of Paris.

Paradoxically, when you checked some of the lesser pre-1992 Who's Who editions, there are no entries for Boutros Boutros-Ghali. Was it because these reference books could not accommodate government members of over 150 states from Ulan Bator to Bogota? Or was it because up to 1992, Ghali was heeded as 'just another Third World senior civil servant?

Someone close to the Sec-Gen has his own theory. To get into some of these fancy who's who editions you either have to be an international celebrity or alternately you had to fill in the self-addressed enclosed form and return it with a check. The affluent Sec-Gen is known to have a very strong dislike for writing personal checks. Whatever the amount.

Today, the sec-gen is facing trying times. Having come to the UN at the age of 69 on a straw poll vote thanks to President Mitterand's unflinching lobbying, Ghali failed to endear himself to Madeleine Albright, the dreaded American representative to the UN.

Moreover, Ghali hasn't scored well with Albright's big time bosses. Which goes to prove that despite his African-Arab-Christian-secular background and his marriage to a granddaughter of Ostjuden rabbis from Eastern Europe, something went wrong where it counts most: philosematic Washington.

This one time, Professor Ghali n'a pas su plaire aux souverains.

Yet based on precedent UN votings we know nothing is ever final when it comes to choosing a new chief. The last word on who will be the next Sec-Gen has yet to be heard. And with Ghali's propensity to make spectacular comebacks à la Prince de Talleyrand, for all we know, the next Sec-Gen could be... Boutros Boutros-Ghali.

I have read with great interest your article on Boutros-Ghali as well as some of the other articles on Egypt's modern history. Although, I do not agree with your article on Boutros-Ghali, let me thank you for your interesting and entertaining articles on many aspects of Egypt's recent history that are difficult to find in regular sources. They provide a very good source of information. I would like however to object to your reference on Youssef Wahba's ministry as a "purported" ministry in your article on Boutros-Ghali. Webster's definition of the word suggests "to have or present the appearance, often false, of being or intending". He did form a cabinet from October 1919 to May 1920 that was as legitimate as those that preceded and came after it. His ministry was composed of a Copt and several Moslem ministers all of whom participated in subsequent cabinets. I understand that you may object to the ministries formed during the period 1914-1924, but they were legitimate governments.

Regrettably, Youssef Wahba's role is generally remembered by his tenure as Egypt's second and last Coptic Prime Minister and not by some of his other accomplishments. For example, some historians write that after he resigned he abandoned his public career, shaken by the opposition to his Ministry. In fact, he was elected in 1924 (not appointed) a Senator for Attarin, Alexandria in Egypt's Parliament with the support of the Wafd. Between 1924 and 1930 he had a very active senatorial life heading the finance commission, foreign affairs commission as well as the commission for the reply to the King's speech.

Also, his premiership is portrayed as an attempt by the British to create dissent between Copts and Moslems. Documents released many years later by the PRO, show this interpretation to be untrue. The British so wanted to form a strong Ministry that would be able to balance Saad Zaghloul's negotiations in London. A Coptic Premier would implicitly acknowledge that the true representative of the Egyptians was Saad and the Wafd. It was the King who insisted that Wahba take on this role to avoid having the British declare Egypt a colony. Saad went to Youssef Wahba's house on his return to thank him for saving the situation during this critical period. I would refer to an article I published in 1989/90 (?) in the Arabic newspaper WATANY on Youssef Wahba.

Subject: Boutros Ghali's new book I am reading the BBG book now, and so far, am not terribly impressed. In fact, I am on page 104 and I find what I read a bore and incoherent, in the sense that there is not apparent logic in the sequence and choice of events, but maybe it will get a little better with Camp David. The part on Idi Amin and Bokassa were funny, though, and he is talking about many people and many events I know of, so I am reading on.

Subject: Boutros Ghali We Don't All Know and his new book

Boutros Ghali has his books written for him. He himself never pretended that his own inputs exceeds retrieving events and memories from the little notebook he usually tucks into his jacket pocket. The rest is done through ghostwriters. One however commends him for having the guts of admitting, blatantly, that he can do very little without his ghostwriters. He boasted about it to Douglas Hurd, who was not terribly amused by the revelation. After compiling masses of sitcoms, anecdotes, satirical comments, even Jokes, he would mark certain parts to be documented. The editing is anybody's headache but his. If it is French stuff, pass it on to Shafik Shammas. If English it used to be--at least until 1994--Murad M. Wahba. As for his Arabic ghostwriters they were several, one of them was definitely Dr. Magdy Wahba, whose death was a great loss for Ghali who wept--literally--upon hearing the sad news. Was Ghali in fact crying for a loss of his lifetime helper or the great scholar Professor Magdi Wahba was?!

Subject: Your article on Boutros Ghali

I enjoyed reading your paper on BBG but I am wondering if you were able to establish the relation between BBG and Al Ma'alem Ghali who was the first of them all (Ghalis). I am married to one (a Ghali) and as far as I know this Ma'alem was a Minister of Finance, and a bandit ?

Subject: Your article

Thank you for your enlightening article on Boutros Ghali. Before going any further let me introduce myself, my name is M. F. Makeen. I am a 30 year old Copt, at the last stage of a Ph.D. in law, London University. Your article raised interesting issues, to mention a few: the origin of the Ghali family; the obvious weakness of the ex-SG; and above all the unease of some members of the international community with his appointment. I would like to mention at the outset, without trying to defend the man, that being a Copt undoubtedly affected the way Boutros Ghali lead his life. That is not to say that Ghali was ever interested in Coptic affairs or their well being, but rather the sense of insecurity that the majority of the Copts share, which ultimately leads to a long journey of seeking acceptance.

Since Nasser, Copts lost all interest in political life, and those few Copts who pursued political office had to fully deny their Coptic identity. By denying one's identity, one has to find an another that he/she could fit in. I am not sure that Ghali ever found another identity that he could claim as his own. Leaving all that aside, an issue that I could not understand was whilst Ghali lead his life holding the pragmatic approach in high esteem, his last six months as the SecGen reflected a different personality. In insisting to publish the report on the Israeli attack on the refugee camp, he seemed to take sides, something which he did not often do. Especially since his report could have only pleased the Arab nations, which for most of his term of office treated him as persona non-grata. Furthermore, he was a good academic and intellect, but never obtrained any training in administration, as you correctly pointed out he was always the minister without a ministry. Thus, we should give him the benefit of doubt in that respect.

Subject: B. Ghali

1. I thought that Ibrahim El Wardani was a Copt. The secret society that

selected him for the assassination used him so it would not be attributed to

secterian hatred. My maternal grandmother toild me that Ghali's

assassination was a cause for jubilation. I also thought that he was killed

to stop his proposal for extending Suez Canal lease.

Reader Comments

Date: Sun, 2 Oct 2005 23:47:29 +0200 (CEST)

From: Aswan Shade: obrown1st@yahoo.fr

Subject: the Ghalis

As I am making some research about my family, I came across your site and read you articles regarding my mother's cousin, Boutros Boutros Ghali.

Of course, I would like to shed some light on the connection between Mo'alem and Boutros Ghali the 1st...for all those who are interested.

Can you tell me how to post a description on your site...and maybe I could create an online family tree and send it over. I have already built a page with all the pictures of the Ghalis that I have so far, starting as far as of Zaki Ghali, grand son of Mo'alem Ghali, my great-grandfather. Maybe you also could provide me with great informations on Moa'alem Ghali, brother of Boutros Ghali the 1st's grand parent

Sincerely yours,

Mr B.O Ghali

Subject: Boutros-Ghali's article

Date: Fri, 04 Jul 1997 20:11:31 -0700

From: Sadek Wahba swahba@husc3.harvard.edu

Organization: Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences

Sincerely,

Sadek Wahba

Date: Wed, 09 Jul 1997 07:26:58 -0700

Former Egyptian Ambasasador

Date: Thurs, 10 Jul 1997 12:06:38

Unsigned

Date: Thu, 15 Oct 1998 08:32:26 -0400

From: "Gamil Sadek" sadek@concentric.net

Please let me know.

Thank you

Gamil Sadek

1882 Norwood Avenue

Ottawa, ON

(613) 521-8008

Date: Mon, 19 Oct 1998 10:59:29 +0100

From: mmakeen@sas.ac.uk

To sum, Ghali could only be understood in light of his Coptic identity that he endeavored to deny.

I would be delighted to hear from you.

All the best, and well-done, nice article.

Makeen F. Makeen.

Date: Thu, 24 Jul 1997 09:37:25 -0700

From: "Mohamed B. Trabia" mbt@me.unlv.edu

I am still reading your articles. I have two comments on B. Ghali's article:

2. Can you find out if Ghali's family descends from Molem Ghali who was the

chief tax collector during Mohamed Ali's early reign? I am always intrigued

about this possibility. Perhaps Dr. Ghali himself can shed light on this

issue if you are in touch with him. My mother told me that he wrote new

book. She was going to buy it.

Sincerely

|

|