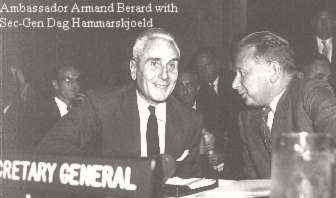

IT WAS AS A HIGH school senior in Westchester, New York, that I observed France's Permanent Representative to the UN debate the thorny resolutions surrounding the Arab-Israeli conflict. I am not sure whether Ambassador Armand Max Jean Berard (1904-89) was the Security Council president at the time, but seen from the Council's Visitors Gallery, he seemed to tower over his colleagues as they huddled around the legendary horseshoe table. Berard was one of the UN giants and that had little to do with his 1.92 meter frame or his chock of white hair which earned him the nickname of Fujiyama from his Japanese friends.

IT WAS AS A HIGH school senior in Westchester, New York, that I observed France's Permanent Representative to the UN debate the thorny resolutions surrounding the Arab-Israeli conflict. I am not sure whether Ambassador Armand Max Jean Berard (1904-89) was the Security Council president at the time, but seen from the Council's Visitors Gallery, he seemed to tower over his colleagues as they huddled around the legendary horseshoe table. Berard was one of the UN giants and that had little to do with his 1.92 meter frame or his chock of white hair which earned him the nickname of Fujiyama from his Japanese friends.

These were the turbulent '60s, and the Arab states had just taken a humiliating battering from Israel during the June 1967 Six-Day War. It was obvious even to the undiscerning observer that Arab delegates weren't faring any better in the UN corridors than had their counterparts at the battlefront. And despite the USSR's procrastinating support articulated by its ambassador the distinguished Nikolai Federenko (later, Jacob Malik), America, through it's UN representative, The Honorable Supreme Justice Arthur Goldberg, was again threatening to Veto with the full backing of the powerful Jewish Lobby, the White House and the American Congress.

Apart from being an earlier version of Madeleine Albright, Goldberg was so involved with Israel's well-being that he often outdid his Israeli colleague, Mr. Gideon Rafael, who sat confidently at the far end of the table. In the critical days before, during and after the 1967 War, the US extended more support to Israel than any time since the crucial UN debates in 1947 on the establishment of the Jewish State.

While the American administration decided the policy line in Washington, Ambassador Goldberg (later, Charles W. Yost) ensured its successful implementation in New York. Goldberg firmly opposed the linking of the cease-fire resolution with an injunction of withdrawal to the former armistice lines, and helped defeat all proposals to saddle Israel with the responsibility for the war and to restore the defunct armistice regime of 1949. All that was left for the long-faced Arab representatives was to wiggle, quibble, prod and plead whenever they were not engaging in endless diatribes and aphorisms. And while their verbal vehemence continued to captivate the unenlightened masses back home, it had a downright negative impact in the UN's exalted halls. Incapable of convincing anyone or anything with their outdated slogans, it looked like they had also lost the diplomatic battle. It was left to the Big Four-France, UK, USA, USSR- to broker out a workable Middle East peace arrangement. One of the Big Four was Armand Berard.

While the American administration decided the policy line in Washington, Ambassador Goldberg (later, Charles W. Yost) ensured its successful implementation in New York. Goldberg firmly opposed the linking of the cease-fire resolution with an injunction of withdrawal to the former armistice lines, and helped defeat all proposals to saddle Israel with the responsibility for the war and to restore the defunct armistice regime of 1949. All that was left for the long-faced Arab representatives was to wiggle, quibble, prod and plead whenever they were not engaging in endless diatribes and aphorisms. And while their verbal vehemence continued to captivate the unenlightened masses back home, it had a downright negative impact in the UN's exalted halls. Incapable of convincing anyone or anything with their outdated slogans, it looked like they had also lost the diplomatic battle. It was left to the Big Four-France, UK, USA, USSR- to broker out a workable Middle East peace arrangement. One of the Big Four was Armand Berard.

A headline in the New York Times described Berard as "a diplomat with many talents". He was regarded by the diplomatic fraternity as a legend at the Quai d'Orsay. His postings and interests said as much. He was one of the few French diplomats who had done the 'ROBERTO' (Rome-Berlin-Tokyo) circuit.

As a young diplomat, Berard had worked under Francois-Poncet, France's reluctant ambassador to Hitler's Germany. In her book Through Embassy Eyes, Martha Dodd, daughter of US Ambassador William E. Dodd, recounts how, during the heyday of the Third Reich "it was young Armand Berard, who came often [to the American Embassy on Tiergartenstrasse, Berlin] and who represented the real link between the French and American Embassies." Berard returned for duty in Germany two more times during his rising career. In the postwar years he served in Rome and Washington before being appointed by General De Gaulle as France's ambassador to Italy and Japan. He was twice his country's Permanent Representative to the UN.

As a young diplomat, Berard had worked under Francois-Poncet, France's reluctant ambassador to Hitler's Germany. In her book Through Embassy Eyes, Martha Dodd, daughter of US Ambassador William E. Dodd, recounts how, during the heyday of the Third Reich "it was young Armand Berard, who came often [to the American Embassy on Tiergartenstrasse, Berlin] and who represented the real link between the French and American Embassies." Berard returned for duty in Germany two more times during his rising career. In the postwar years he served in Rome and Washington before being appointed by General De Gaulle as France's ambassador to Italy and Japan. He was twice his country's Permanent Representative to the UN.

It was during the early part of his second tour at the UN (1967-70) that I saw him in action. With a brilliant career behind and knowing this was his last foreign posting, in true Gaullist fashion, Berard was not ready to tow the American line. In fact, he was going to give the Arab moderates a fair hearing contrary to what most Western Security Council members had done. Notwithstanding their dependence on Arab oil, their countries had been seduced by Israel's lightning victory and were now taken in by the superior pro-Israeli propaganda war that followed.

Unlike his counterparts, Berard spoke little and only when he had something important to say. His was one of the few unbiased voices whether at the horseshoe table or at his home on Park Avenue where several of the Big Four meetings took place on a rotating basis. With exemplary skill and tenacity, he proposed and argued realistic resolutions to the exasperation of the Israelis and their Washington friends who had become suspicious and resentful of Berard's involvement.

Meanwhile, the Arab representatives, like their governments, seemed out of touch with the gameplan of the Western media and the bipolar realpolitik. This is perhaps why, Berard seemed even more appealing to the moderates than he would have been under normal circumstances.

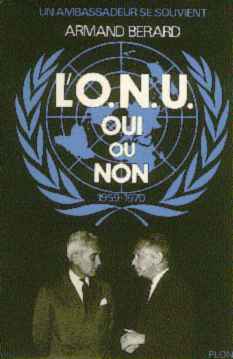

But who was this Frenchman the Arabs had grown to admire and respect? Alluring, he most definitely was in a way only the French know how. His integrity and eloquence were reinforced by a literary background that was almost a family trait. His father, Victor Berard (1864-1931), was the noted archeologist and Hellenist who translated The Odyssey and wrote several classical works on Homer and Ulysses. Armand Berard's maternal great-grandfather started the reputed publishing house Librairie Armand Colin in the middle of last century. When he would retire from diplomatic life, Berard authored several important works supplementing L'Allemagne et la Re-organization de l'Europe which he had written in 1944. Un Ambassadeur se Souvient came in five volumes: Au Temps du Danger Allemand; Washington et Bonn; ONU, Oui ou Non; Une Ambassade au Japon and Cinq Annes au Palais Farnese.

But who was this Frenchman the Arabs had grown to admire and respect? Alluring, he most definitely was in a way only the French know how. His integrity and eloquence were reinforced by a literary background that was almost a family trait. His father, Victor Berard (1864-1931), was the noted archeologist and Hellenist who translated The Odyssey and wrote several classical works on Homer and Ulysses. Armand Berard's maternal great-grandfather started the reputed publishing house Librairie Armand Colin in the middle of last century. When he would retire from diplomatic life, Berard authored several important works supplementing L'Allemagne et la Re-organization de l'Europe which he had written in 1944. Un Ambassadeur se Souvient came in five volumes: Au Temps du Danger Allemand; Washington et Bonn; ONU, Oui ou Non; Une Ambassade au Japon and Cinq Annes au Palais Farnese.

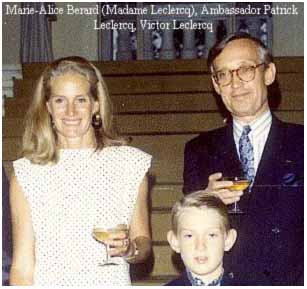

ANOTHER ARAB-ISRAELI conflict and several peace treaties later, I was introduced to Madame Patrick André Leclercq, the tall blonde wife of France's Ambassador to Egypt. The year was 1993 and the venue was the palatial French Embassy residence in Giza. I found the hostess unpretentious, attractive and refreshingly candid. I had been forewarned of her daring by some of her snipping peers. On the other hand, they had omitted to mention her openness, generosity and turbulent simplicity. Perhaps it was out of envy for her decontracté style and her knack for making every individual feel like he or she was the guest of honor at her receptions.

Since I knew her only as Madame Leclercq, I never made the connection with Armand Berard, the champion of my war-torn teenage days in New York. True, I had read somewhere that he had two daughters-Marie-Alice and Monique-but that was ages ago and absolutely irrelevant to the present. It was therefore a most pleasurable coincidence when I established the connection Madame Leclercq was actually Berard's daughter. And yet, somehow, I wasn't surprised. There was a je sais quoi in her reminiscent of the grand diplomate. I am most certainly not referring to her exuberance or her enthusiastic outbursts, characteristics totally inconsistent with her stoical father.

Meanwhile, of Ambassador Patrick Leclercq, I knew only what I had heard from the diplo-vine. He is an eight-to-eight workaholic who likes to start his day with a spot of golf and has a marked preference for cigars. He is courteous, discreet and cultivated; traits of the trade not unknown to successful Frenchmen in his position. But with time, and as I got to know the Leclercqs better, I observed that like Marie-Alice, Patrick was an admirable host and a wonderful raconteur endowed with agility, tact and a refined Gallic sense of humor.

Like it or not and at the risk of being called a Frog-lover, as far as Egypt's large diplomatic community is concerned, the Leclercqs stole the show hands down. I am positively not alone when I say the First French Couple of Egypt made an inimitable impression on Cairo. They appreciated the city and its distinct character, and more importantly, its people. And I don't mean Cairo's gilt-edged two hundred!

Cairo reciprocated. The proof is in the pudding or in this case Om Ali. Ever since rumors started on Patrick's nomination as his country's next ambassador to Spain, which was where his first foreign posting took place back in 1967, Cairene society has been in a tizzy. Everyone wants to bid them au revoir the Egyptian way. The farewell dinner and lunch queue is one of the longest and most intense this decade. Under the circumstances, perhaps it is better they leave us next week otherwise we may start hearing of serial cholesterol attacks.

I think that Patrick and Marie-Alice Leclercq sensed during their five years in Egypt how their warmth and hospitality have been genuinely appreciated. But one thing must be said. Had Armand Berard been alive today, he would have realized that his balanced understanding for the people of this country had not been misplaced in the agitated '60s. Equally important, he would have been doubly proud both as a father and father-in-law.

On behalf of all those who know the Leclercqs, A bientôt.