|

egy.com suggests following articles

|

EGY.COM - PERSONALITIES

THE EPHEMERAL REPUBLIC OF KOM-OMBO

by Samir Raafat

Egyptian Mail, February, 03, 1996

extended version in "The Egyptian Bourse" published by Zeitouna 2010

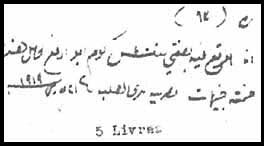

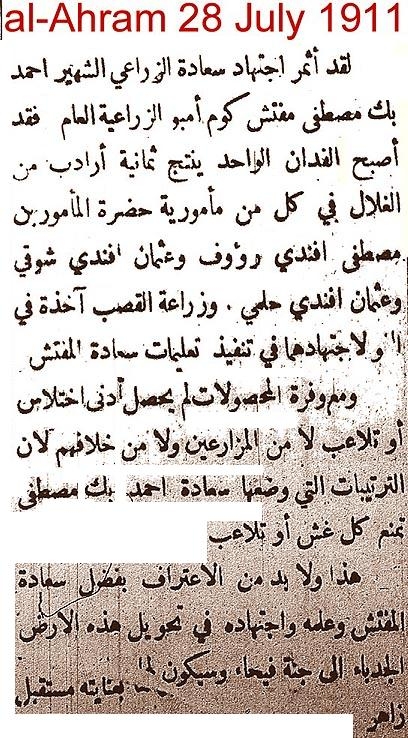

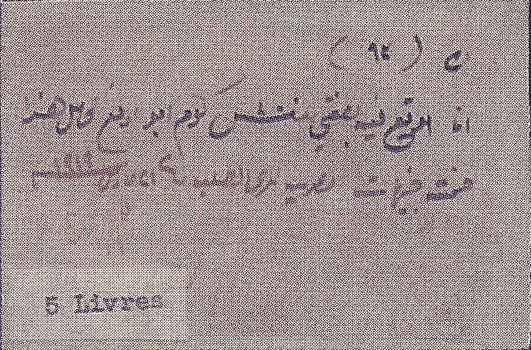

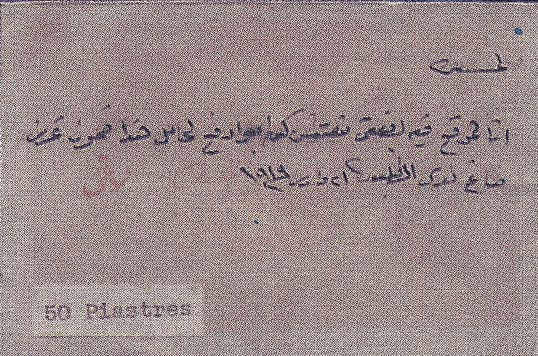

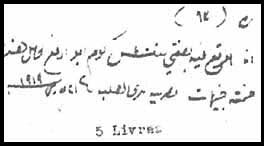

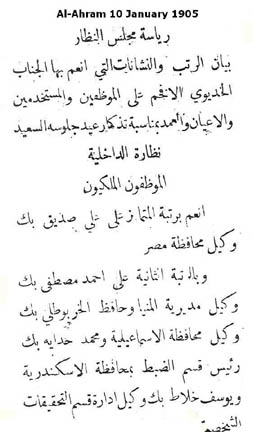

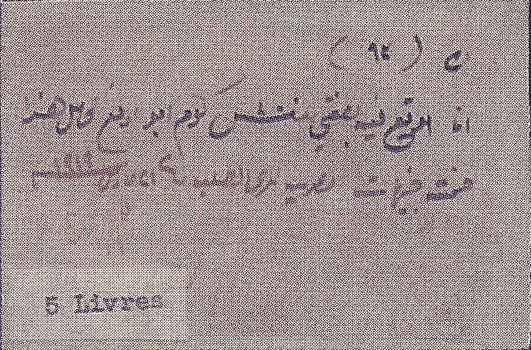

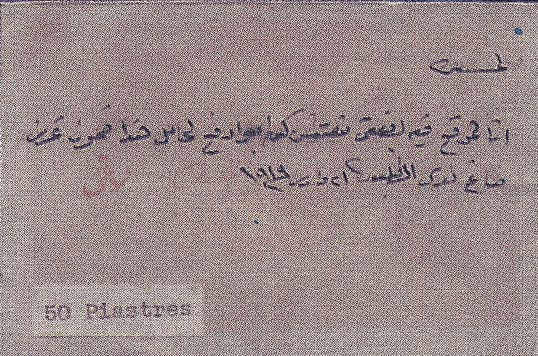

(S 93) I the undersigned in my capacity as Mufatish of Kom-Ombo hereby guarantee to honor this note and the payment of five Egyptian Pounds upon demand. 21 March 1919

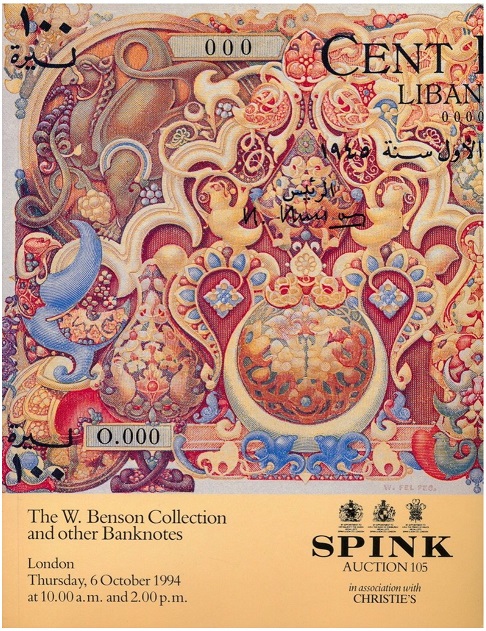

below al-Ahram 2 November 2008

flyer photo courtesy Tarek Farid Mansour

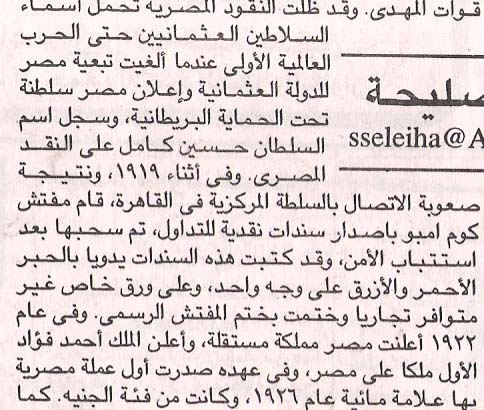

It was announced in London on Thursday, 6 October 1994, that Spink's, in association with Christie's of St. James, would hold the W. Benson Collection and other Banknote Auction.

"Nine hundred and eighty lots covering some of the world's oldest and rarest currencies are expected to be sold to the highest international bidders at Christie's Ryder Street Rooms between 10:00 and 14:00", boasted the related flyer.

Although its banknotes were not half as elegant or colorful as the rest, lot No. 567 was earmarked at 5,500 to 6,500 Pounds Sterling making it THE most expensive of the entire collection. More perplexing is the banknote didn't resemble any customary legal tender. What then, was the reason behind the exorbitant price?

Spink's auction catalogue describes item No. 567 in the following terms:

"A series of Banknote from Wadi Kom-Ombo [a town in Upper Egypt] printed for use during April and May 1919 in the event of Kom-Ombo being cut off from the outside world by political unrest in the area. This set comprising 5-, 10- and 50- piasters and 1-, 5-, and 10- Livres believed to be the only set extant, the balance being recalled and replaced, except one set retained by the Wadi Kom-Ombo Company. All the notes are plain script on card with semi-circular handstamp, SOCIETE ANONYME DE WADI KOM-OMBO. Script reads 'I am the inspector who signed at Kom-Ombo, pay to the bearer on demand'."

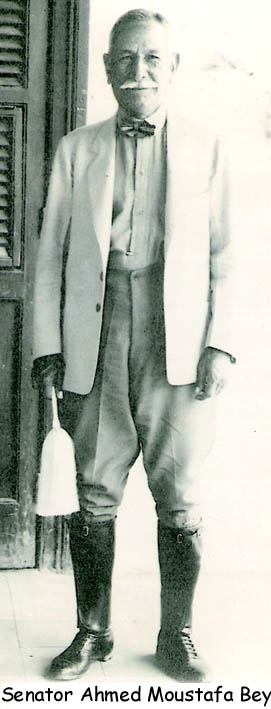

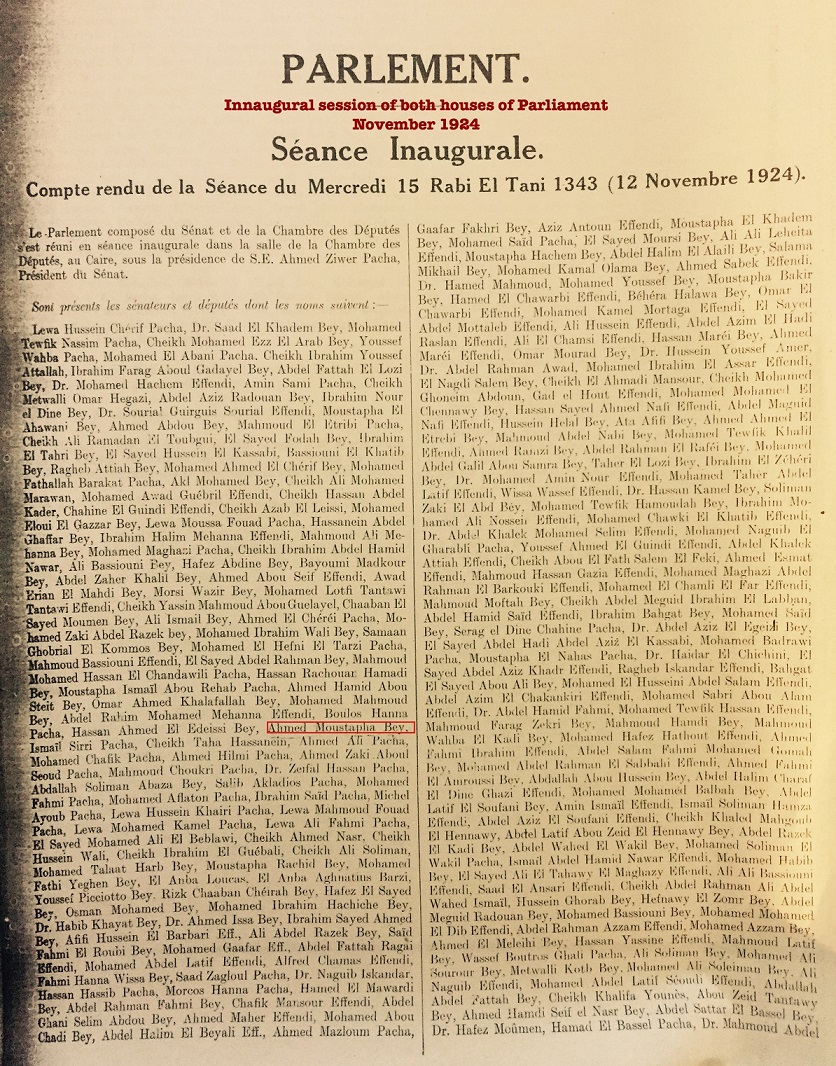

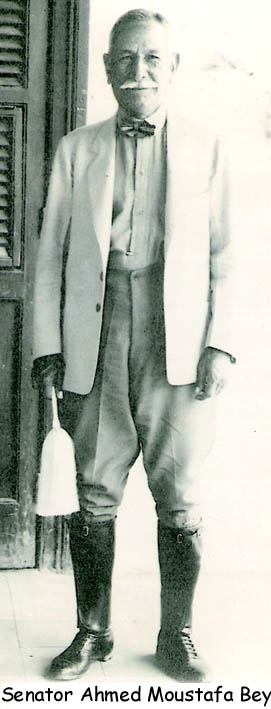

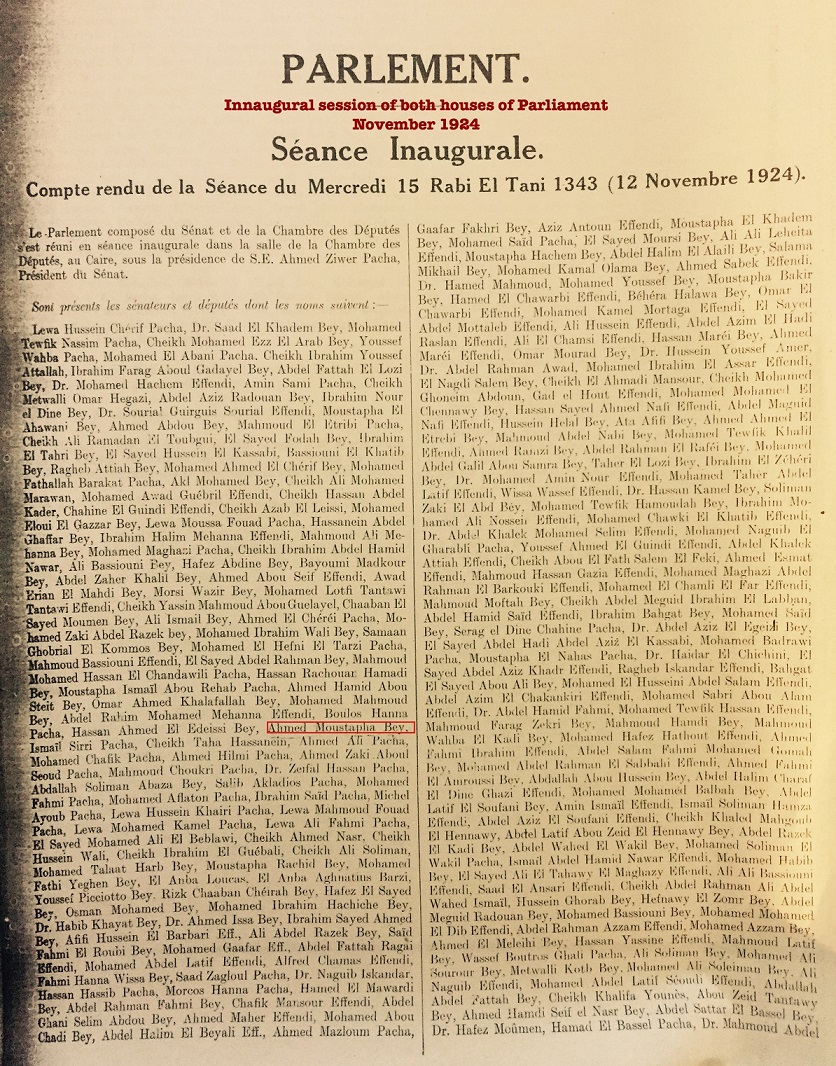

What is not mentioned in the photo or anywhere else in Spinks' catalogue for that matter, is that the notes described in lot No. 567 were signed by Ahmed Moustafa Bey (d.1940), the veteran Mufatish and senator from the district of Kom-Ombo in Upper Egypt.

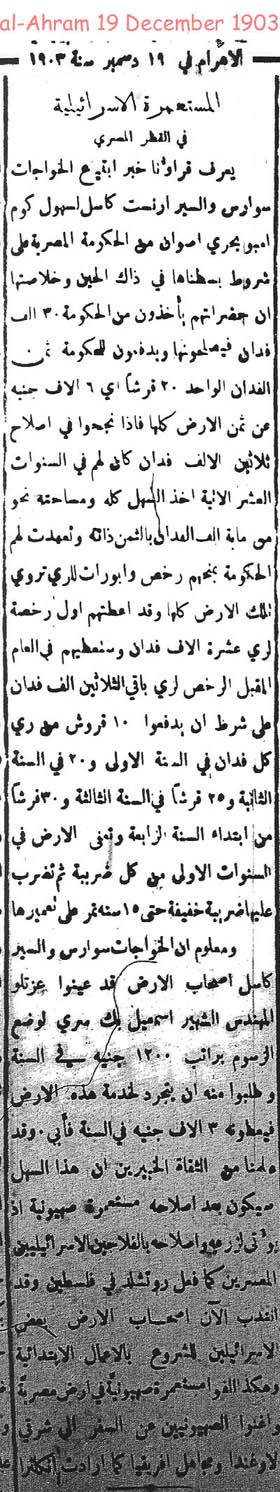

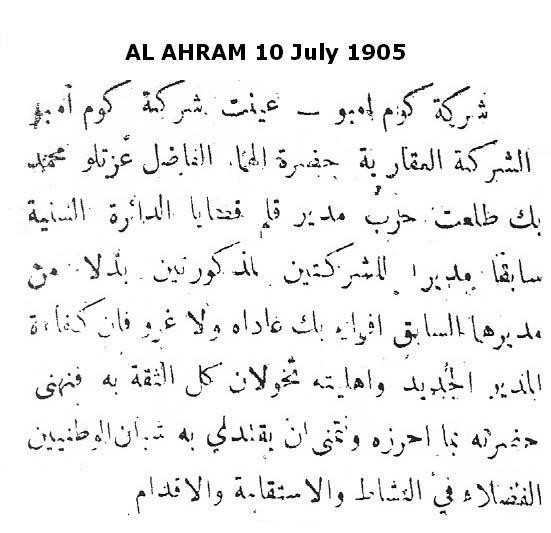

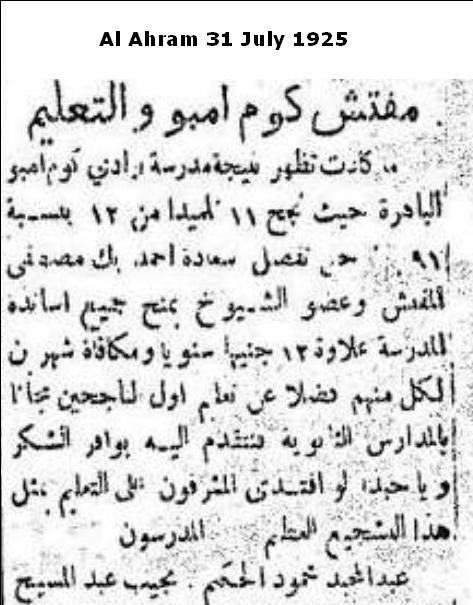

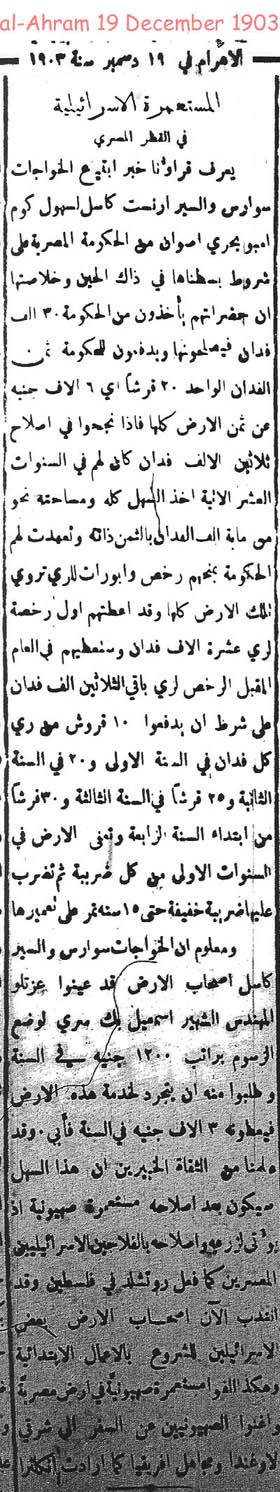

Ahram article accuses Kom-ombo company founders of creating a Zionist settlement in Upper Egypt

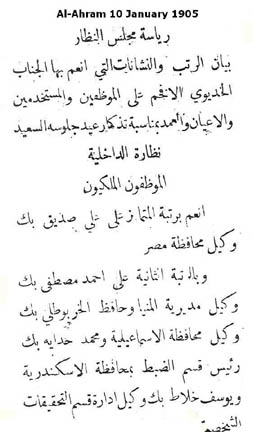

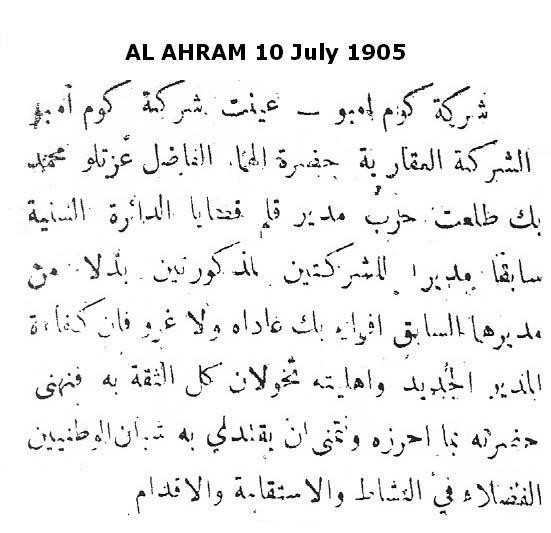

Talaat Harb began his career working for the Suares brothers. In 1905 the Jewish consortium headed by Sir Ernest Cassel appoints him head of legal section in the Kom-Ombo company replacing Ephraim Adda Bey. 18 years later Harb emulates the Suares brothers and co-founds the Misr Group of companies

February 1932: L-R: Senator Ahmed Moustafa Bey with Talaat Harb Pasha, Sherif Sabri Pasha, Prime Minister Ismail Sidki Pasha, future prime pinister Mohammed Mahmoud Pasha, sugar company director Henri Naus Bey, former prime minister Adly Yeken Pasha, Ralph Victor Harari at Wadi Kom-Ombo Company

KOM-OMBO AND THE SUGAR INDUSTRY

With the completion in 1902 of the Aswan Reservoir and its subsequent heightening in 1909, several hundred thousand feddans were brought under cultivation for the first time. The heretofore unknown abundance of water during the dry season allowed for perennial irrigation so that a second crop was planted each year.

These important developments led to a doubling of land value, the allocation of the new acreage to sugar cane and the burgeoning of sugar factories all over Upper Egypt. Overnight, sugar production became Egypt's single largest industrial employer and sugar cane cultivation the nation's second largest cash crop.

This was a reversal from when Egypt's sugar industry had fallen on hard times, once during the reign of Mohammed Ali and again following the 28 August 1905 suicide of French sugar king Ernest Cronier.

It was Cronier, together with Henri Says & Cie of Pairs and banker Raphael Suares of Cairo, who re-launched Egypt's sugar industry in 1892. Thirteen years later Cronier's failed speculation on the Paris Bourse led to his hastened demise and the insolvency of Egypt's sugar consortium.

But with the heightening of the Aswan Reservoir, a second generation of sugar factories expanded across Upper Egypt including an important one in Kom-Ombo, a village north of Aswan bordering the (Ernest) Cassel irrigation canal.

With the availability of year-round water, Kom-Ombo, so far only known for its Ancient Egyptian temples, quickly turned into a thriving company town where all able-bodied men, women and children worked for the sugar industry.

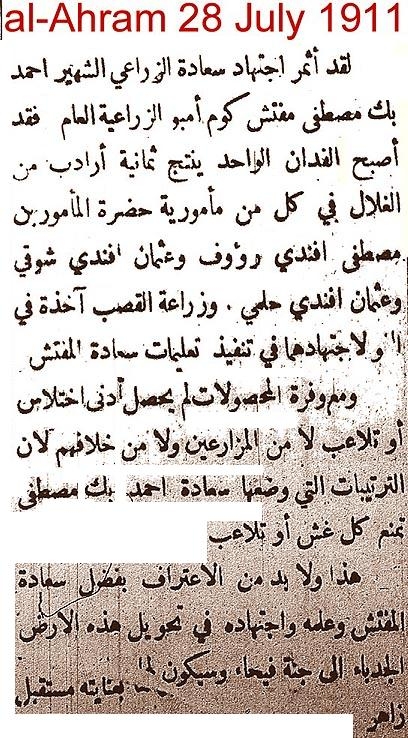

Yet, besides it fantastic turnaround from a forgotten village with old relics from the past to a thriving crop producing center, Kom-ombo became an issue with those who saw things otherwise. Conceived and created by an international group of Jewish capitalists, editorials came out referring to Kom-ombo as an "Israeli Colony on Egyptian soil." Al-Ahram, in its 10 December 1903 editorial went as far as saying that the Upper Egypt town was about to replicate of what was going on in Palestine. "Once Kom-ombo plan is up and running its owners plan to import Zionist laborers to till the land, similar to what Rothschild did in Palestine. Hence, Zionists need no longer to go to Eastern Uganda as suggested by the British."

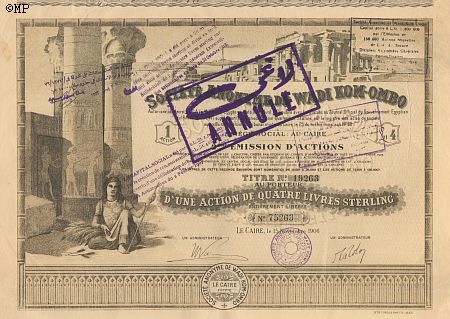

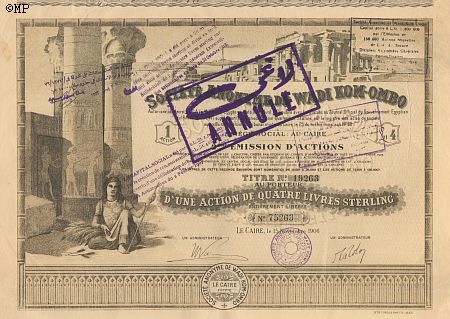

1906 share certificate of the Wadi Kom-Ombo company

"Societe Anonyme de Wadi Kom-Ombo" founded by the Suareses and Cattauis

Under a regime of laisser-faire and with the blessings of company chairman Youssef Cattaui Pasha and deputy chairman Talaat Harb Pasha, Egypt's sugar affairs were left entirely in the hands of Belgian sugar expert Henri Naus Bey.

From his smart office on Cairo's Sheik Abou al-Sebaa Street the diminutive Belgian ran the Societe Generale des Sucreries et de la Raffinerie d'Egypte single-handedly from 1902 or thereabouts until he died in 1938. It was also thanks to Henri Naus and his Belgian associate Albert Ceyssens, that the old Jamaican cane imported in the days of Viceroy Ibrahim Pasha (r. 1948) was replaced with the superior Javanese POJ 105 variety.

It was no coincidence also that the owners of the Sugar Company were the principal shareholders of the agricultural concerns that operated and managed Upper Egypt's vast sugar plantations. One of these mammoth concerns was the Wadi Kom-Ombo Company, the brainchild in 1904 of Sir Ernest Cassel of London, the same man who, in 1898, had heavily invested in the construction of the Aswan Reservoir.

Cassel's associates in Egypt included Raphael Suares, Sir Elwin Palmer of the National Bank of Egypt, Sir Victor Harari Pasha of the ministry of finance, agronomist Victor Mosseri Bey, engineer Youssef Cattaui Pasha and banker Robert Rolo (later Sir Rolo). It was Sir Victor, who upon retiring from his government job in 1905, oversaw the new company's financial affairs.

Shortlisted to run the operations of the Wadi Kom-ombo Land Reclamation Company were three capable men. Ismail Sirry Pasha who politely declined the offer; Daira Saneya Inspector General Birch Pasha (d. January 1913), and agriculture expert Ahmed Moustafa Bey.

Before becoming deputy governor of Minieh Province, Ahmed Moustafa Bey started out as the nazir--agricultural superintendent of his grandfather's (Hassan Sharkass Pasha) estates . Now, brimming with experience, Wadi Kom-Ombo Company entrusted him with the management of thirty thousand feddans taftish, much of it allocated to a new sugar cane variety. Henceforth, he was referred to as al-Mufatish.

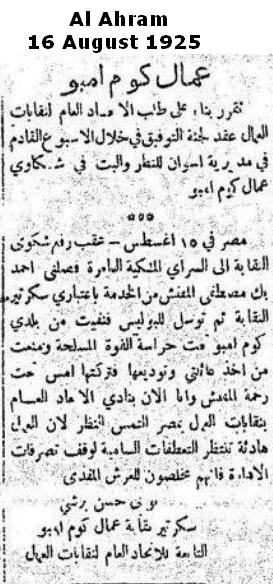

al-Ahram commending Ahmed Moustafa Bey for his excellent management of tafteesh Kom-ombo

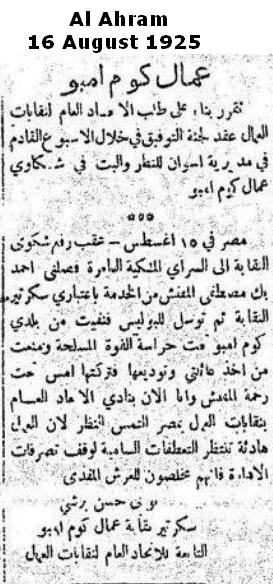

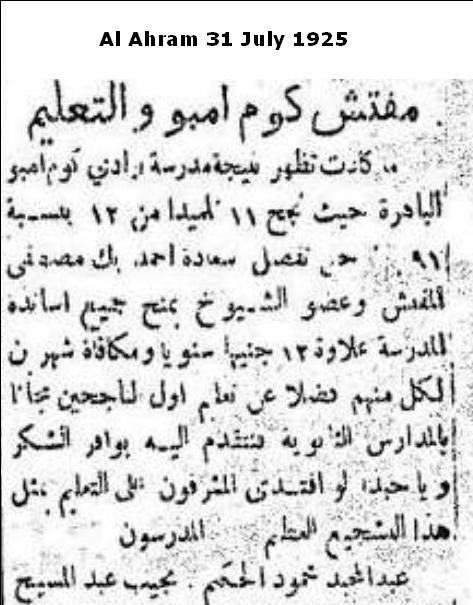

below: Senator Ahmed Mustafa rewards professors and students at Wadi Kom-ombo School for excellent performance

Kom-Ombo now a virtual company town with Ahmed Moustafa Bey in charge, the Mufatish was regarded by the fellahin (peasants) as their de facto employer and paymaster. And if his already heavy charge was not enough, each year, during sugar cane harvesting season, Moustafa's manpower would quadruple in size. This also meant wages had to be renegotiated and special cash payments handled. But the 1919 harvest season would be very different for it was the year when the Mufatish was confronted with much more than he bargained for. Here's why.

Despite all the trappings of statehood --ceremonial head of state, council of ministers, flag, customs and postal administration-- Egypt in 1919 remained a virtual British colony or Protectorate. All civil servants, the sultan down to the smallest army officer, were ultimately accountable to Lord Allenby, the British High Commissioner. If the Mufatish was considered Kom-Ombo's paymaster, Allenby was regarded by most as the paymaster of Egypt.

Yet, even during the British Protectorate, Egypt retained its own national currency. Why then did the Mufatish of Kom-Ombo resort to printing his own tender in 1919? Surely it wasn't so that it could be sold at exorbitant prices at a London auction seventy years later!

The reply to this question lies in the British Foreign Office. A clue, however, can also be found in al-Ahram's 14 September 1994, issue where an article applauds Kom-Ombo's Mufatish for his daring and initiative.

"Qualities" the article says, "which are altogether lacking in our contemporary civil servants, for here was a man who, against all odds, was unafraid to take crucial decisions in times of crisis, and who in the heyday of British occupation, was not prepared to procrastinate or wait for orders from the consul, the sultan, the king or the president."

"Why is it that 80 years later" bemoans the frustrated writer, "our senior civil service officials are afraid or unable to take the simplest and most minor resolution?"

The "crucial" crisis the article alludes to are the events of the 1919 upheaval which ultimately brought Egypt a measure of independence. Egyptians had discovered Saad Zaghloul, a candid patriotic man who stood up to British oppression and publicly opposed its policies. Behind Saad Zaghloul Pasha rallied an entire population.

But instead of hearing out the nationalists and negotiating a settlement, the British High Commissioner, on March 8, 1919, deported Zaghloul Pasha and his senior backers, Ismail Sidky Pasha and Mohammed Mahmoud Pasha (all three future prime ministers of Egypt), to Malta. Lord Allenby was not tolerating any independist talk.

Within days, Egypt flared up in an unprecedented revolt resulting in a total breakdown of vital transport and communication system with a near crippling effect on the nation's economy. Railway lines were torn up, stations burned, telephone and telegraph wires cut. This was followed with a general strike by Egyptian officials and the resignation of the Egyptian government.

The paralysis was complete. Cairo was isolated from the rest of the country. British high-handedness had not paid off. Zaghloul was released on 7 April 1919.

As far as the British High Commissioner and his advisors were concerned, the time had come to re-assess the damage, to pick up the pieces and to restore a new modus vivendi. But first, there were accounts to be settled. One of them was in Kom-Ombo.

THE MOMENTARY MONETARY AUTONOMY OF KOM-OMBO

Summer comes earlier in Upper Egypt than it does in Lower Egypt. It is not unusual therefore, that a crop is attended to in the south several weeks before it is sowed or harvested in the Delta. Likewise, a delay of a few days could jeopardize an entire crop, which is why the outbreak of March 1919, coinciding with sowing time in Kom-Ombo, placed an entire harvest in very serious jeopardy. Cut off from the company's head office in Cairo, liquidity dried up overnight. As a result, hoarding begun in the Kom-ombo and its dependencies. The local bank branch which served Kom-Ombo was suddenly out of funds and new cash shipments were improbable since no trains arrived from Cairo.

An unforeseen crisis confronted the Mufatish. If he did not pay his inflated labor force there would be no crop. If there was no crop there would be no harvest and the sugar factories would come to a grinding halt. A whole year's sugar production would perish. The man of the hour had to come up with a solution. Fast.

Barter was out of question. Even Kom-Ombo had subscribed to 20th century practices and was not about to revert to bartering tribal beads for kilos of grains. The only feasible alternative for the Mufatish was to print his own money. A daring move since no comparable precedent existed in Egypt's modern history. Even Mohammed Ali Pasha had abstained from such a move fearing the reaction of his sovereign in Constantinople.

Ahmed Moustafa Bey's money was a rudimentary affair. No coins, just plain cut paper bearing a simple handwritten inscription promising to pay the bearer the listed amount upon demand. It was signed by the Mufatish himself. The five, ten, fifty piastre denominations as well as the one, five and ten-pound notes were neither backed by gold or silver, nor were they convertible into any known legal tender. The only cover was Ahmed Moustafa Bey's integrity and the standing he enjoyed in Kom-Ombo. The fellahin, the migrant laborers, the tradesmen and the civil servants agreed to go along.

Once the new money was circulated, the sugar cane crop was as good as saved and the sugar factories were ensured their quota of raw material. The Mufatish represented law and order for the entire district. Kom-Ombo had become an autonomous mini republic.

The implication of Ahmed Moustafa Bey's resolve was not lost on the British. Here was an independent spirit capable of pragmatic solutions. Translated into colonial jargon, a dangerous subversive mind which coped with complex situations, qualities the foreign occupier could not appreciate in others but himself. The revolutionary Mufatish had to be taught a lesson for his ingenuity.

Even before alleged accusations started to pour in, Ahmed Moustafa Bey was arrested. Charges ranged from his having disrupted the railway service in his area, to his harboring subversive elements. Under prevailing marital law the Mufatish was guilty of high treason deserving capital punishment.

Moustafa Bey remained imperturbable, confidant that a harsh sentence would trigger spontaneous uprising from Kom-Ombo to Aswan. Moreover, the company's powerful shareholders brought considerable pressure on London so that death sentence be commuted to house arrest. A powerful group of Jewish financiers with long reach, they were keen to have the man who had proved his mettle reinstated.

newly syndicated workers complaining of Senator Ahmed Mustafa's treatment

It came as no surprise therefore when, three years later, the Mufatish was appointed senator of the district of Kom-ombo at the inauguration of Egypt's first constitutional parliament during King Fouad's reign. Soon enough the new senator faced a new crisis but this time it had little to do with anti-colonialism and more to do with suppressing a rising workers movement across Egypt. Since Moustafa Bey refused to recognize the vociferous ad-hoc syndicate formed by his workers, their leader promptly took to the press denouncing the senator as a despot and a union-buster. In his book Workers on the Nile 1882-1954, Stanford University's Joel Beinin gives us an insight to this matter.

"The Kom Ombo workers mentioned earlier found their newly revived union under attack by the same Ahmed Bey Mustafa supervisor of the estates project, powerful local notable, and member of the Senate who had destroyed their first union formed in 1919. As long as he lived, he threatened, there would be no union. He was above the law. It would seem likely, given subsequent developments in the political arena, that Ahmed Bey got his way in the end."

But, meanwhile, what became of the inspector's celebrated banknote?

These were gradually retired from the market in exchange for National Bank of Egypt legal tender. The few specimens that survived are coveted collectors' items appearing from time to time at Christie's of London or Sotheby's in New York.

For the non-numismatics, the Mufatish notes represent an important milestone in Egypt's modern history. And for al-Ahram's dispirited contributor and the thousands who agree with him, Senator Ahmed Moustafa Bey's tangible initiative and his ephemeral republic of Kom-Ombo are documented testimonials that in days gone by, public administrators had the guts to take decisions.

- Ahmed Moustafa Family tree (incomplete)

- An excellent 150-page book with illustrations on the history of Egypt's sugar industry entitled "Henri Naus Bey: Retrieving the Biography of a Belgian Industrialist in Egypt" by Uri Kupfershmidt, appeared in Fall 1999, published Koninklijke Academie Voor Overzeese Wetenschappen in Belgium, ISBN 90-75652-16-X

Reader Comments

|

see al Wafd Daily, 19 August 2009

Date: Fri, 13 Apr 2001 13:57:23 +0200

From: Viatcheslav Gavrilov

We came across your great article "THE EPHEMERAL REPUBLIC OF KOM-OMBO" on the

web. Can you grant us permission to present it also on our site

http://www.collectornetwork.com for many world paper money collectors? It would be a

great gift for them.

Best regards,

Viatcheslav Gavrilov

General Manager

CollectorNetwork.com

www.collectornetwork.com

Subject: El Mufattish

Date: Tue, 26 Dec 2000 14:24:04

From: Aziz Moustafa, Sydney, Australia

This is a story my dad told me years ago yet I will never forget it as long as I live. Grandpa Ahmed Moustafa was the first Egyptian general manager of Wadi Kom-Ombo Co. During the aftermath of the 1919 uprising against the British occupation, my dad and his brother Mahmoud were staying with him at the Company's mansion. Because of his political activity and enmity to the British, there was, as mentioned in your article, a price on Grandpa's head dead or alive. A staunch Wafdist, Grandpa wanted desperately to send vital information to Saad Pacha Zagloul's partisans in Cairo. But since all roads and communications were cut between Upper and Lower Egypt, it was dad who volunteered to be the messenger. Wearing a galabieh and takieh with a tanned face, he hid the documentation in a secure belt around his waist. Pretending to be a deck hand he hitched a ride from Kom-ombo to Cairo aboard a feluka. Having finally made it to Cairo after numerous security stops he found Saad Pacha's house surrounded by British troops. This time around dad was obliged to disguise himself as a kitchen hand!

|

Email your thoughts to egy.com

© Copyright Samir Raafat

Any commercial use of the data and/or content is prohibited

reproduction of photos from this website strictly forbidden

touts droits reserves