|

|

|

|

|

Cheers to our "talented" literature prize awardee. Your pain his gain !!!

|

|

|

EGY.COM - MAADI

|

|

I learned of Anzac Day the moment I landed in Melbourne, Australia, ten years ago this April. A festive mood prevailed everywhere with flags and buntings decorating the city's thoroughfares and parks as Melbournites prepared to commemorate the anniversary of the epic 25 April 1915 Australian (and New Zealand) amphibious operation on the shores of Turkey.

I learned of Anzac Day the moment I landed in Melbourne, Australia, ten years ago this April. A festive mood prevailed everywhere with flags and buntings decorating the city's thoroughfares and parks as Melbournites prepared to commemorate the anniversary of the epic 25 April 1915 Australian (and New Zealand) amphibious operation on the shores of Turkey.

Ever since the Battle of Gallipoli where Australian fought Turk, the anniversary is a recurring milestone in Australia's history. For Aussies, Gallipoli -- forever romanticized in books and Hollywood movies-- marks a turning point for the youthful federation. In fact, this was the new state's first war ever. What is remarkable however, is that the disastrous war took place thousands of miles from home. The amount of young men who never made it back was so large, that even the remotest bush town was affected. Their best sons were buried on foreign soil.

Seven decades later it was an endless parade down Melbourne's Collins Street with participants looking like they belonged to the Grandpa Brigade. Average age hinged around seventy. Servicemen bedecked with medals and citations were WW2's Aussie veterans for survivors of Gallipoli had either passed away or could no longer walk the extra mile.

But what I didn't expect to find one week later at a Canberra museum was the recurring mention of my suburban hometown in Egypt. What, in the name of waltzing Matilda could have linked outback Bushies from Australia, to the town of Maadi located at the opposite end of the globe! This, I vowed find out.

When WW1 broke out in the summer of 1914, the newly federated state of Australia had turned 14. Prior to 1901, the states of Queensland, New South Wales, Tasmania etc. were separate British crown colonies settled mostly by bounty hunters, sheep farmers (remember Colleen McDowal's bestseller Thornbirds) and convicts. Incidentally, not all Aussie immigrants were murderers and rapists. Back then, steal a banana in London's Haymarket and it was more likely that you ended up in Australia. Penal justice has since changed.

It all started when a Serb militant killed the heir to Austria's throne in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914. The ensuing funeral cortege had hardly reached the imperial crypt in Vienna and Europe's imperialist powers were already polarizing themselves into two opposing camps. Simultaneously the British Empire mobilized all the able-bodied men it could muster in the UK and its far-flung dominions including Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. What were empires for if they couldn't provide human fodder.

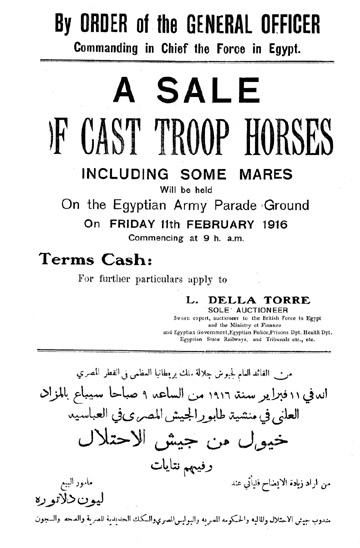

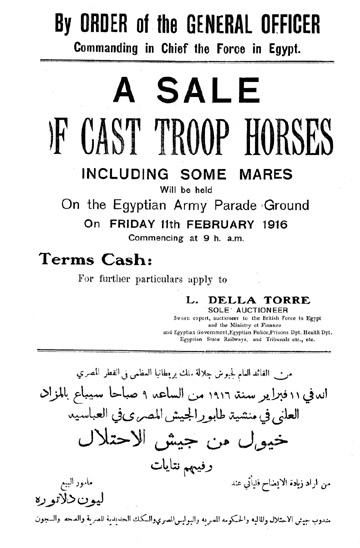

Traveling by troop ships and requisitioned P&O liners, thousands of Aussies disembarked in Suez and Port Saiid on what was to be the first leg in the long and murderous bloodbath of Gallipoli, and later to Palestine. Most of the young diggers had never before left the Southern Hemisphere let alone Australia. Neither had their horses for that matter. In those days, wars were fought with horses and rifles, not h Uzi machine guns and Pershing missiles.

Once in Egypt the new arrivals needed a rehab period to familiarize with the local climate and to await further training and instruction. Australian camps mushroomed overnight outside Cairo's empty expanses where the large-boned Aussie horses could come round after a grueling five week journey. In Cairo alone there were camps at Zeitoun, Mena House, Heliopolis, Kasr al-Nil and the Citadel.

Outside Cairo there was the famous base of Mo'ascar near Suez. In Alexandria it was al-Hadra and in Upper Egypt, Sohag. As for the 1st Australian Light Horse Brigade under the command of Colonel Forsyth, it camped in the vicinity of the tiny new suburb of Maadi.

Barely eight years old, Maadi was under the jurisdiction of the London-based Egyptian Delta Land & Investment Company. Most of the townies were British save for a sprinkle of Germanics who were automatically branded enemy aliens, their homes and assets confiscated by her Britannic Majesty's government.

The Maadi Brits were mostly glorified administrators in the employment of the Egyptian government. After four centuries of Ottoman rule and thirty years of British military occupation, the latter won out. On 19 December 1914, the British deposed the Turkish-appointed khedive of Egypt. Henceforth the Nile valley was declared a British protectorate.

The Anglo-Egyptians, as the British administrators were called, were the undisputed masters in these parts. Those living in Maadi were not amused with the Aussie arrival. These were rowdy, undisciplined and unkempt men. They couldn't even speak proper English and for all they knew some of these low-brows were Jack-the-Ripper types.

Maadi's Brits' did not waste time in communicating their strong reservations to the commanding officers. So much for neighborly relations!

On the other hand, Australian Comfort Committees under the directorship of a Mr. H.E. Budden and other Australian individuals sprung up everywhere. Their main function seemed that of distributing billies to the troops at every given occasion. Billies were cooking vessel which, during wartime, were packed with buttons, shoe-laces, chocolate, postcards, soup tablets, insect powder, puzzles, safety pins, bandages, hair and tooth brushes, tooth powder, reading matter, tin openers, tinned fish and penknives.

Aside from the Comfort Committees in Cairo, there was one in Helwan. It was reachable by train or via Kitchener's desert road especially built by civilian inmates at Tura penitentiary. The penitentiary itself would shortly be converted into a military prison for Turkish and Austro-German prisoners of war.

The stalwart, sunburnt men in their broad-brimmed hats traveled from Maadi to Cairo by rail getting off at Bab al-Louk Station. From there it was walking distance to the comfort committee's headquarters or by ghary (horse-drawn coach) across town to the fleshpots of Ezbekiya were everything could be had for the right amount of coppers. City favorites were the American Comosgraph picture theater, the Salle Kleber which also showed films, the Cairo British Recreation Club and the Obelisk Hall on Emad al-Dine Street. There were of course the brothels at the Birket district off Ezbekiya gardens.

While it was no secret how the Maadi Brits felt about their khaki-clad neighbors, how then, did the men from down under feel about Maadi? According to the Diggers' monthly magazine Kia-ora Coo-ee, Aussies referred to Maadi as the garden city. At least this is how they described it in the magazine's 15 March 1918 issue (cost: 3 piasters). "There are plenty of trees in Meadi where trees grow fast. You have to take a snapshot to photograph the place, the vegetation growing so fast that a time exposure is impossible."

Another description elaborates: "This is the town of the garden homes. Talk to any resident of Meadi and you will find that he is equally proud of his home and of the town, for Meadi is a community and life there is veritably laid in green pastures. This does not mean, however, that it is a 'bush' town - though there are bushes and trees a-plenty. The very streets of Meadi are gardens. The Delta Land Co. sees to it that proper care is given to the trees and lawns and that spraying, pruning and other such necessary operations are done at the right time. They are fortunate in having among the residents of Meadi the state entomologist and other experts from the Egyptian Department of Agriculture and so in these respects the town is pretty well 'fathered'. There is little in the line of town beautification that is left undone.

As a town Meadi is in its infancy. But it is a pretty healthy and, one might even say, ultra-modern infant although, unlike many youngsters, it always has the look of wearing its Sunday best. Meadi does not look like a 'boom' town, with vacant lots and advertising signs galore, and as a matter of fact, although there is a splendid selection of good real-estate property available, one might pass through the town and not suspect a lot for sale. Everything looks spick and span and well cared for, the simple reason being that, until actually built upon, every lot is kept under cultivation. That is why Meadi looks like a garden.

The Australian Light Horse Unit was camped at the edge of the desert south of Maadi's Road 84 up to the borders of Tura town. It was flanked between the Digla railway line and the Khashab Canal which, in those days, was exposed to direct sunlight, the Australian eucalyptus trees having only just been planted. Quick to do business with the troops was Blume's so-called Tavern and the Café du Nil.

To capitalize on the beer-drinking troops the town's two cafés were purposefully situated next to the sleepy Maadi railway station. In a news item reported in the EgyptianGazette, sentries were posted on both sides of the railway lines their eyes keen to discover any loiterer round the mountains of fodder, the rows of field equipment, the mounds of baggage, of food etc. all of which awaited removal to the nearby camp.

The Egyptian Gazette goes on to described the Aussie camp in its 18 December 1914 issue. "Although the camp is not yet quite fixed, the men seem cheerful and at home. Large wood fires burn beneath and around oval iron pots of tea; toast too, seems a great favorite, baked and often sadly burned in the wood ashes. The many lines of beautiful and much loved horses strike the onlooker immediately; they have practically constant attention night and day. Being packed on the boats as they were the whole time from Australia, standing for seven or eight weeks has for the time weakened and stiffened their legs and joints and at present not one of them is being ridden. They are exercised daily, at first gently, increasing to 10 mile exercises and training they are now undergoing. There are wild and almost wild horses amongst them many of which were presented to the regiments before they left."

"The lines of tents are like most lines of tents but for a few of the officers' which showed an almost Oriental brightness with their linings of brilliant orange and the huge canteen tents built of native tenting. Mascots of the regiments are of-course a chief and interesting sight and a motley crew they are. One regiment is the proud possessor of two great birds, of the kind called the laughing jackasses whose shrieked of mirth can be heard by the inhabitants of Meadi half a mile away. There was also the rock kangaroo or wallaby."

From other sources we learn the camp was not without its own amenities. There was a cinema tent where mass or Holy Communion was celebrated each morning. A recreation tent provided by the Maadi residents. There were also a boxing ring, a billiard saloon, a stadium and for lack of a nearby parade ground, Maadi's tennis courts were used. A Maadi Soldier Club was opened in December 1915.

From the Light Horse Brigade's Routine Daily Orders we glean interesting snippets which shed light on the camp's impact on the immediate neighborhood and on the outlying communities. Much in there would suggest there were severe communication problems and culture gaps between the Aussie digger and the Egyptian native. By natives the Aussies meant the villagers, felaheen or peasants and Bedouins who populated the outlying area. It was not intended to describe the pasha, the bey or the effendi class who lived in Cairo proper. And yet, the Egyptian gentry themselves were not too keen on the Aussie.

In his biographical essay, The Prison of Life (AUC Press, 1964), author playwright Tewfik al-Hakim has this to say. "We in the cities did not experience the effects of the war to any great extent, except in so far as we had to put up with the insolence of the Australian soldiers and the drunken English. They grabbed what passers-by had in their pockets at night and what street vendors had in their hands by the day." Words that hardly flatter Egypt's unwelcome guests. But, as we'll find out these feelings are reciprocated by the Aussies.

Following are is an Australian army directives listed in the Routine Daily Orders for the period 1915-16 (source: the Australian War Memorial, Canberra).

All native villages and cemeteries are out of bounds to the troops; twelve Sudanese have been appointed as gaffirs for the camp; gambling with natives will in future be considered a criminal offense; men are warned against familiarity with the natives; all ranks are warned against molesting natives and it is to be clearly understood that any soldier interfering with their property will be court marshaled and is liable to a term of imprisonment with hard labor.

Men are warned that the practice of taking fruit from the gardens of the natives must cease; Owing to the number of thefts lately all natives except those employed in the horse lines or with passes signed by the adjutant must be kept out of camp; it has been reported that soldiers traveling by train have taken possession of compartments in carriages set apart for ladies, thereby preventing veiled ladies from traveling.

If further complaints of this nature reach the camp commandant all leave will be stopped. A special military train now runs from Bab al-Louk to Maadi at 10:00 p.m. Men are requested to travel by this train in preference to the 09:30 p.m.; all guides, dragomen and other natives found in camp without a pass or committing misdemeanors are to be handed over to lieutenant Jordon, officer in charge of military police, Maadi. The list goes on.

On the other hand, in an effort to remain in the good books of Maadi's British population we find the following:

Permission to exercise horses in Maadi will not be granted. (Months later) Attention is again drawn to the fact that no horses are to be exercised in the streets of Maadi; horses must never be ridden at a faster pace than a walk when riding outside the camp, motor cars not to exceed 6 miles per hour; all forms of horse racing are strictly forbidden; damage has been done to Maadi trees through men tying their horses thereto. This practice must be discontinued at once; all men appearing in Maadi except when on fatigues must be properly dressed, that is shirts, putties with shorts or riding pants, leggings and jackets. Belts must be worn but not bandoleers. On or after December 15 shorts must not be worn; Shops near the Maadi railway station in future (December 1915) will be out of bounds at all times except by pass; the practice of drilling on the Maadi Public Tennis Courts and the grounds immediately adjoining is hereby prohibited. The ground is for the use of the residents of Maadi and not for military purposes; It has been brought to notice that men are in the habit of digging in search of antiquities. This practice must at once be put a stop to.

There was also the problem of hygiene and refuse. From the Daily Routine Order we learn that stable and kitchen refuse was purchased by a local native Hamouda Mohamed while carcasses were removed by the Manure Co. of Egypt at one shilling per each animal. Other daily orders include:

Soldier suffering from venereal disease are to report themselves without delay; all hair must be cut short; all natives found defecating or micurating will be handed over to the Native Police for punishment. Officers Commanding Mounted Brigade will instruct their Sanitary Squads to see that the Natives Latrine are carefully disinfected; horse manure form the lines of the 7th Regt. must in future be put in a heap on the far side of the ditch running behind the men's mess room, in rear of the shoeing-Smith shop in line with the men's latrines; All Europeans and native employees in canteens, officers messes and kitchens, ice cream makers, vendors etc. and hair dressers are to be dressed in clean white overalls; it has become the custom for soldiers to pass urine in other places than in latrine buckets and urinals. This is a filthy practice and men doing so will be crimed; European employees in the camp found to be dirty or verminous as to their clothing are to have their names and that of their employer forwarded to the A.P.M. of the district in which the camp is situated with a view to the passes of such persons not being renewed; drinking water at the railway station is forbidden as this water is drawn from the sweet water canal.

The Australians had their own clinic in Maadi. It was was attached to the 1st Australian Stationary Hospital under the command of a Lt. Col. Bryant. Staffed by three resident nurses and three medial officers it closed down on 26 March 1916 but not before the sewage problem was fixed whereby both catch pits were completely cleared. (house is still in existence today).

When hostilities ended in October 1918 with the defeat of Germany, British-occupied Egypt, which had been so far spared the vagaries of bloodshed, was ready to wage its own war of independence against the Anglo-Saxon colonizer. Ironically, it was to the Diggers who survived the carnage in Gallipoli and elsewhere that the Brits turned to in order to quell Egyptian uprisings and civil disturbances. This did little to endear the Aussie to the already hostile local population.

When the orders finally arrived for the Australian troops to pack up they were only too happy to comply. Homeward bound at last. They too had had enough of the Gypos and their repugnant British administrators. As for those diggers who never made it back from the war front, they were buried near battlefields such as the cemetery at Anzac Cove in the Dardanelles. Others rest near their temporary bases such as the ones in Egypt. Little did they know their sons would be back twenty years later to inflate these same cemeteries some more.

Today, like yesterday and the day before, the spirit of Anzac lives on. Once a year, the small Australian and New Zealand communities in Egypt gather at the Commonwealth War Graves (formerly the Imperial War Grave Commission) in Heliopolis or at Alamein to commemorate their valorous soldiers who died in WW1 and WW2.

This year, Anzac Day will be celebrated in Egypt on April 26 with Ambassador Michael Smith presiding. While the enlightened Australian diplomat is fluent in Arabic having served extensively in the Arab World (Algeria, Tunis and Cairo) perhaps he also knows Turkish. If he does, he will surely find wisdom in the words of Moustafa Kemal Attaturk Father of the Turks (and Turkey's first president) who, as a young colonel, had led the valiant Turkish troops against their equally valiant enemy come from so far to fight them: Those [Australian] heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives... you are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. To us there is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mohammeds where they rest side by side here in this country of ours... You, the mothers, who sent their sons from the far away countries wipe away your tears; your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land they have become our sons as well.

|

|

|

|