SINISTER NEIGHBORS OF THE WORSE KIND

The Nazi Next Door

by Samir Raafat

Egyptian Mail, 28 January 1995

TODAY'S feeble attempts at bringing perpetrators of genocide to justice evokes memories of the late fifties when, at the height of the Cold War, a tall German doctor and his family showed up at a pension-turned-residence in the Cairo suburb of Maadi. At the time, the doctor introduced himself to the townies as Karl Debosch, pronounced 'Dabous' by Mohammed, his Egyptian barber on Road 9.

Maadi was then a tiny community when Digla still represented its desert outback. These were the late 50s and like any small town, Maadi had its own well-tuned grapevine addressing each rumour and gossip with equal alacrity. Nonetheless, the arrival of a yet another German doctor was no big deal. Nonetheless, over the years Maadi had its fair share of European doctors.

Ever since its creation in 1907 Maadi was home to hundreds of foreigners including Austrians and German doctors. Some old timers still remember Doctor Rudolf Ferdinand Amster who had been a member of Khedive Abbas Hilmi's coterie of Austrian aides, and how Amster later joined the exiled Khedive in Vienna after WW1.

Following Amster's departure his Maadi neighbor, Doctor Emil R. Lichtenstern, took over as medic up until the 1940s during which time he shortened his name to Lister. And there were the other resident medics : Isaac Gerson, Max Ratgheb, Paul Balog, Maurice Hauff etc..

But Doctor Debosch of the 1950s was different. Tiny tell-tale signs said as much.

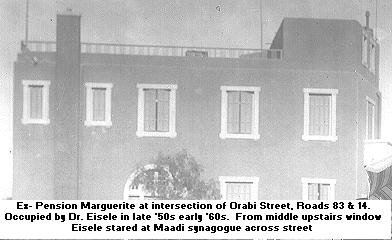

A particular item which caught everyone's fancy was a report that Debosch was seen recurringly staring from his upstairs window at the building across the street. The focus of his attention was always the same; somehow, the small Maadi synagogue on Orabi (ex-Mosseri) Avenue fascinated the German doctor.

Curiously, no one ever saw Debosch outside his house. Neither did anyone run into Frau Hedwig at the Maadi Sporting Club, a must if you wanted to blend into Maadi's mainstream. Ditto for Road 9 where Maadi's few shops were located. The Deboschs, who seemingly never shopped, appeared there only when the doctor needed a haircut or a medicinal drug from the local pharmacy.

The couple neither entertained nor accepted invitations. True, there were several Germans and Austrians seen entering or leaving the Debosch's villa, but if some of these Aryan visitors sported assumed Arabic-sounding names, the rest felt comfortable under their original names: "Herr Pils", "Herr Brandner" etc.

Meanwhile, the German nuns at the St. Borromeo Convent situated at the north end of Maadi's Road 12 vouched that Doctor Debosch was a devout Roman Catholic. On the other hand, Maadi's faithful swore he never made it to mass at the Holy Family Church on Road 15, just a hundred meters from his house. Probably had nothing to confess, claimed some of the regular churchgoers.

The only way you could meet or talk to Doctor Debosch was by becoming his patient.

One German-educated Maadiite, Amina Radi, remembers that when she called on her school-friend Weiland, the doctor's son, she was surprised to find the Debosch's downstairs hall filled with Germans. Some were the parents of her other classmates at the German School.

As it turned out Debosch had twice more German patients than did his Egyptian rival, Doctor Tousson Salem who was himself half German through his mother.

Amina also remembers how, at the German school, each time Doctor Debosch's children walked into a classroom, professors talked in hushed tones to one another. Sometimes they referred to them as the children of the damned --whatever that meant!

One Maadi morning, speculation and gossip regarding the Debosch family exploded to untenable proportions. A booby-trapped letter had blown out the eye of Maadi's postman the previous day. The letter had been addressed to Doctor Karl Debosch!

Maadiites were overwhelmed with apprehension. WHO EXACTLY WAS DOCTOR DEBOSCH?

Almost simultaneously, stories, some of them comical, started to spread.

"Debosch was an unlicensed practitioner" claimed the wife of the town's Egyptian doctor who, from the start, deeply resented the new arrival.

"Rubbish!" said the self-important spouse of an army general. "This is no doctor but a great scientist." Forever pretending she was in the political know, the general's wife ascertained to her eager audience that khawaga Dabous was a rocket scientist, hence targeted by those who didn't want Egypt to have far-reaching weapons.

But, according to the Jewish wife of a famous Egyptian journalist, Dr. Debosch was in fact a wanted war criminal. During WW2 he had made lampshades using human flesh. The Czech-born woman went on to claim she had spat on the Doctor when they met per chance on Maadi's commuter train.

"He's a dog killer of the worse kind" cried the English bird-lady who lived on the other side of Maadi. Having seen a dead puppy dog near the Doctor's house, she promptly reported him to the PDSA.

Reporting him to the PDSA was unnecessary claimed Madame Leila Nagati, an Egypto-Swiss who lived in the small brown Meyr Biton building across from Doctor Debosch's house. The German doctor's end was evidently near. A closet detective, Nagati had cleverly connected the handsome foreigner who had recently moved into the ground floor of her Orabi Avenue building, with Doctor Debosch. "My neighbor is an undercover agent from Israel. He is here to finish off the Doctor" she told anyone who paid attention. "I hear his transmitter crackling late at night and have already reported him to the police. It later turned out that Laila Nagati was half right. Her neighbour was indeed an Israeli spy.

Just as the German doctor had his antagonists, he also had the ready support of his apologists who defended him with equal enthusiasm.

"He's a desperate henpecked introverted artist" whined a struggling Maadi painter who admired the Doctor's masterpieces. Apparently, these hung on his living room walls. As for the elderly couple from Luxembourg who lived a block away from the German doctor, they swore he was the best ENT specialist Maadi had ever known. "He found a cure for my husband" nodded the grateful Madame Warda Bircher-Blazer.

The stories changed each day.

What nobody knew and few suspected was that Doctor Debosch was one and the same as Doctor Hannes (Hans) Eisele of Buchenwald fame. His wartime specialty had been the injection of experimental fluids into human guinea pigs.

Why then was Doctor Debosch not in a post-war German jail? Why wasn't he in Spandau prison sharing a cell with the Alexandria-born Rudolf Hess, the fabled author of a quixotic peace flight to Scotland in May 1941.

Most certainly Doctor Debosch's story was an unusual one. It would be many years later when a curious Maadi neighbour (yours truly) pieced scanty snippets of information about him. Yet the story remains somewhat incomplete. In any case here's a sample of what was later confirmed from valid sources.

Doctor Hannes Eisele was of pure Aryan stock, his "Aryan Certificate" said as much. It listed the names, places and dates of birth (and death) of both sets of grandparents. Where necessary, the certificate explained causes of death--vital information to a Third Reich which promoted racial purity.

Eisele was the son of modest village folk. Born on 13 March 1912 in the small town of Donaneslingen, he grew up in the laender of Baden. Whereas his father Hans was a painter-laborer his mother Emma Bullinger was an ordinary housefrau.

Even before Hans Senior passed away in 1934, young Hannes supported his family taking on part time painting jobs. At 21 Eisele joined the Nationalist Socialist Democratic (NAZI) Party and, later that year like many of his generation, he became a member of the Schutzstaffel paramilitary organization or SS --a sure guarantee to upward mobility.

Eisele studied medicine at the University of Freiburg where he became involved in student politics. And later, during the war years, the former student-leader served the Fatherland at different junior officer-level posts, first as a commandant and later, in 1943, as a hauptsturmfuehrer--Captain-Doctor.

Although he didn't appear at any post-war tribunal for crimes against humanity, a US military court in Dachau found Eisele guilty and sentenced him to death. Yet, for some unknown reason, capital punishment was commuted to life imprisonment. Shortly afterwards, in 1952, Eisele was released and allowed to practice medicine in Munich. Evidently, the SS Old Boys network was alive and well in the former Third Reich.

It was only in 1958 that Eisele's medical union card was revoked right after his mysterious escape from Germany. Thereafter, his name became public domain especially since it was brought to the attention of the Bavarian Justice Minister, Dr. Ankermuller.

Yet, by the time a warrant for Eisele's arrest was issued on 28 June 1958 based on incriminating evidence provided by Herr Zommer, a former colleague from the Buchenwald days, the Doctor and his family were safely on board the SS Esperia which had set sail from Genoa for Alexandria the previous day.

If a new identity was in store for Eisele and his family in Egypt, their stay would be short and tumultuous dampened by the fear of being uncovered. In fact, the doctor’s Egyptian sojourn ended in ostracism, malady, and finally in death on 3 May 1967.

Eisele was buried at the German Cemetery in Old Cairo. The paradox here is that he shares the same plot with Doctor Theodor Maximilian Bilharz. While Doctor Bilharz's black granite plaque lists in Arabic and German his wonderful medical achievements, the short inscription on Doctor Eisele's rough tombstone reads simply "Dr. Med. Hans Eisele". Understandably, it makes no mention of any of his medical accomplishments.

Though only a few meters separate the two doctors' final resting places, the chasm between them will never be breached. Not in this world or any other.

photos samir raafat

Robert Fisk: Butcher of Buchenwald in an Egyptian paradise

THE INDEPENDENT - Saturday, 7 August 2010

Not long ago, a Hizbollah fighter in Lebanon insisted to me that there was life after death.

With my fascination for "life beyond the grave", I told him to prove it. "Mr Robert," he replied, "do you believe in justice?" Well, yes, I said, I did. "So do you think there is justice in this world?" Nope, I replied. "Well that proves it. If there's no justice in this world, there must be justice in the next -- so there's another life!"

I remembered this piece of esotericism a few days ago, when in Egypt I bought a second-hand copy of an old book about the Cairo suburb of Maadi, a grand old place of villas -- until it was destroyed, of course, in Cairo's 1970s building plague -- in which British colonialists, Germans and Austrians and Egyptians (many of them Jewish) and Italian and Armenian families made their homes amid parties and tennis matches at the Maadi Sporting Club and the children's college and, during the Second World War, a vast horde of Commonwealth troops waiting for El Alamein.

But one page caught my eye. Samir Raafat, who must know more about Maadi than anyone else in the world, had dug up the story of a quiet German doctor, Carl Debouche, who moved into a bland house on the corner of Orabi Street in 1958. Most of the neighbours, according to Raafat, noticed that he would spend hours at his window, staring at the Maadi synagogue across the road. Then shortly afterwards, an Egyptian postman called with a parcel that exploded in his hand, blowing his eye out. "Debouche" was unharmed. Readers, however, will already have guessed what is to come.

For yes, indeed, "Debouche" had a dark past. He wasn't even "Debouche". His real name was Dr Hans Eisele, former Nazi party member 3125695, former SS Hauptsturmfuhrer (SS no 237421) and convicted war criminal.

He began by fighting on the western front and ended up working in Nazi concentration camps at Sachsenhausen, Natzweiler, Dachau and Buchenwald. According to the American who prosecuted Eisele, Colonel William Denson, Eisele started off as the good doctor, called "the Angel" by prisoners, but steadily became cruel and sadistic, until, at Buchenwald, he was called "the Butcher" because he carried out medical experiments on prisoners, allowing them to die slowly after injections of cyanide.

He was twice sentenced to death (in 1945 and 1947), but both sentences were commuted until in 1952 -- and this showed the degree to which the then West German government connived in helping its war criminals -- he was freed from Landsberg prison. With compensation! So he set himself up as a doctor in Munich and then fled six years later when he was warned he would yet again be arrested.

So those neighbours in Maadi were right to be suspicious. And, of course, if the West Germans were grotesque in their attitude to war crimes, so was Nasser's Egypt, which positively welcomed ex-Nazi scientists and torturers to help to run socialist Egypt. Alois Brunner, the man who sent the Jews of Salonika to Auschwitz, was one of them (until he set off to help Syria's secret policemen) and he may have been one of the men and women who attended Eisele's all-German soirees. Eisele's true identity, of course, meant that he had to close his practice in Cairo and he died a widower in 1967. But he was given a friendly funeral at the German cemetery in Old Cairo.

So, mindful of my Hizbollah acquaintance's belief in the afterlife -- and of the Marriott hotel's advice that in Cairo it might be easier to find a dead man than a living one -- I set off this week to find the last resting place of the Butcher of Buchenwald. It took about two hours even to locate the German cemetery; with infinite irony, it lies only a few hundred yards from Cairo's oldest synagogue and a British Second World War graveyard. But sure enough, the moment I walked through the Teutonic portals, there was a little paradise of tall trees and flowered bushes and -- cut off from the roar of Cairo -- a peaceful garden, its concrete paths washed, its shrubbery carefully cut.

The cemetery keeper's wife, an unsmiling lady who inspected my five Egyptian pound tip as if it might be forged, produced the book of the dead. And there he was, complete with his real identity and his false name. "Eisele, Hans, Dr med. 13/3/12 - 3/5/67, Carl Debouche 1901-1957." There was no explanation for the fake name or the fake dates beside it. Eisele may have invented the first date. But why would he invent the second -- before he even arrived in Cairo? Then there was that slight missing heartbeat when you glanced to the right of the page: "Grave No 99."

No movie would dare carry that cemetery number for a doctor from hell. But the grumbling Egyptian housewife walked me beneath the trees and pointed at a cement rectangle with the number "99" on a small marble plaque and, at the top, a massive piece of black stone -- carved, as they say, "from the living rock" -- which bore the words, crudely and perhaps in a deliberately "Aryan" way fashionable in the 1930s -- "Dr Med Hans Eisele. *13/3/12 + 3.5.1967".

That's all. He got away with it. There is a pink flower and some cabbage-type plants on his well-tended grave. Far from the fumes and chaos of the city he fled to -- far further than the fires of Buchenwald -- tucked away at the side of this pretty little cemetery, the doctor from hell ended up in a little paradise. If my Hizbollah man's theory is right, of course, he has already been sentenced by a judge far more erudite (and a lot harsher) than US Colonel Denson. Be good to know, though, wouldn't it?

From: Tom B. Atkinson [tomjax@bellsouth.net]

Date: November 7, 2006

My uncle has a painting by H Eisele that was painted by him when he was

a prisoner at Landsberg and my uncle was the assistant commandant.

My uncle is still living and has interesting stories about him as well

as the other inmates that he executed and wrote about in a Book, Captor

Captive.

Nephew of Joseph Williams

Email your thoughts to egy.com

© Copyright Samir Raafat

Any commercial use of the data and/or content is prohibited

reproduction of photos from this website strictly forbidden

touts droits reserves