GATES OF HEAVEN

by Samir Raafat

Cairo Times, September 2, 1999

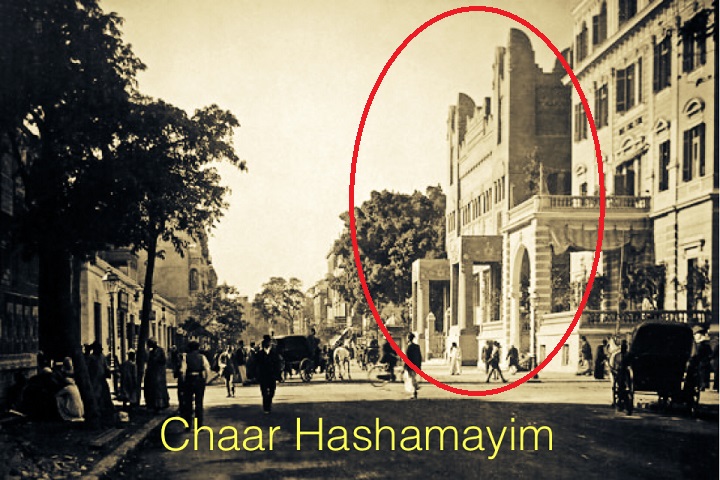

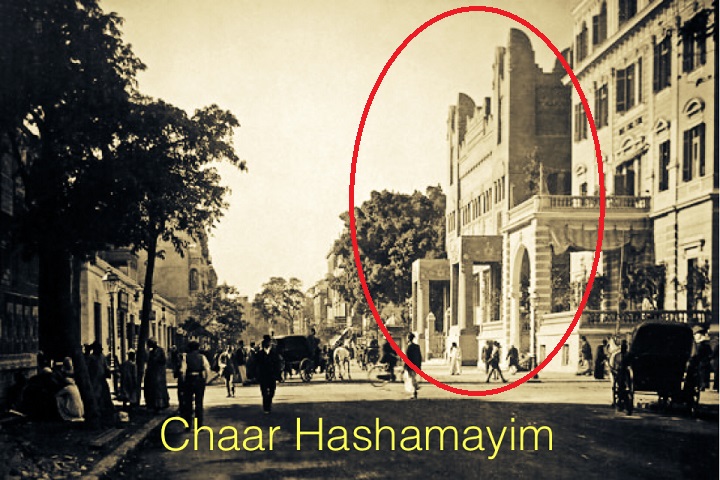

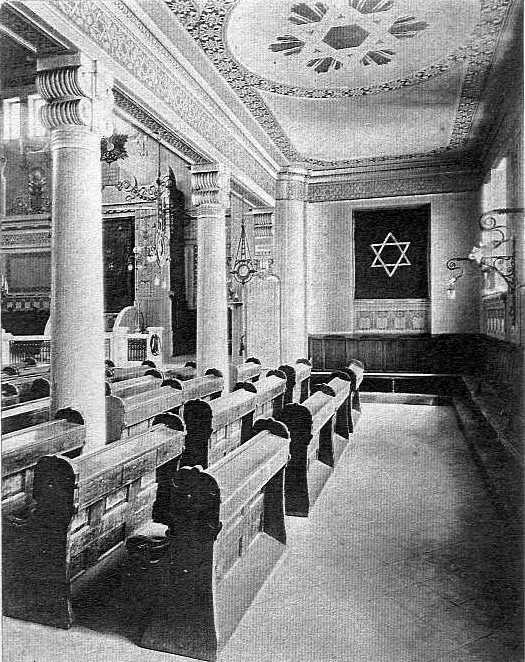

circa 1906

back view

|

|

|

|

|

Cheers to our "talented" literature prize awardee. Your pain his gain !!!

|

|

|

EGY.COM - LANDMARKS - CAIRO - HELIOPOLIS

|

|

by Samir Raafat

Cairo Times, September 2, 1999

circa 1906

back view

In his copious memoirs Sir Ronald Storrs, then a young British diplomat, described it as a "self-respecting but architecturally painful Sephardi Synagogue." This was 1904 and Cairo's newest Jewish place of worship, Chaar Hachamaim-Gates of Heaven, was barely five years old.

Storrs, T. E. Lawrence and others of their genus could not have missed noticing the Neo-Pharaonic temple. Not only was it the biggest structure on Maghrabi (now Adly) Street, but it was also contiguous to that most sacred of colonial sanctuaries, the Turf Club. Later, the club, an abject symbol of British Imperialism in the Middle East, would move westwards on the same street before being torched to the ground during the anti-British riots of January 1952. The Synagogue on the other hand survived intact three bloody Arab-Israeli wars and is still in operation today.

Inside Chaar Hachamaim two large marble tablets on either side of the central nave evidence an engraved Hebrew listing of those resolute men who contributed to the synagogue's barn-raising and helped maintain it for several decades after. With over 100 names historically linked with the country's first privatization in 1898-1906, in a way the tablets are a roll-call of the Jewish financial elite of the time. And for those unable to read Hebrew, they can alternately consult the tiny brass name-plates appended to the benches in the synagogue's main hall. Here again--in latin script this time--we run into the Mosseris, Suareses, Cattauis, Rolos, Adesses, Hararis, Naggars, Cicurels, Curiels, Luzzatos et al. all of whom formed the pillars of Egypt's once powerful Sefardi community.

Collectively the above families accounted for much of Egypt's banks, department stores, transport companies, and urban and suburban developments. In their debt also are two important museums: Bab al-Khalk's Islamic Museum and the Museum of Modern Art. Both were beneficiaries of large private collections. Most notable among them was that donated by Sir Simon Rolo who features as No. 18 on the synagogue's marble tablets. It is no small coincidence that Egypt's first Modern Art Museum was located in a former Mosseri townhouse abutting the Synagogue's rear, at the corner of Mohammed Farid and 26th of July Streets.

A plaque on the synagogue's outer wall, facing the inner courtyard, states that Vita "Victor" Mosseri spearheaded the campaign to erect a synagogue in Cairo's new European district of Ismailia. Missing however is an inscription acknowledging that it was his Cattaui relation who designed it.

Together with his Austrian partner Eduard Matasek (a Roman Catholic), Maurice Youssef Cattaui designed the Gates of Heaven in 1899. Assuredly, Matasek-Cattaui wanted to remind onlookers that Moses had been a prince of Egypt long before he became a prophet. Whether inside or outside the temple, you cannot fail to note the persuasive Ancient Egyptian quality. Perhaps the style was a reminder that Judaism had its origins rooted in the Valley of the Nile; that this was home to one of the oldest Jewish communities in the world.

But if no one gasped at the temple's historical nuances, visitors were nevertheless quick to deride it as some form of hybrid-kitsch and, later, as the perfect set for the remake of Cecil B. DeMille's "Cleopatra."

Another scrap of information gleaned from the Synagogue's wall mounted plaques is that although it was considered a Sephardi temple of worship, several Ashkenazim (Eastern European Jews) contributed to its construction and upkeep. Among them was Phillip Back whose family created the famous international department store Orosdi-Back (now Omar-Effendi in Egypt). Listed as well are Leon Heller, Maurice Schlezenger and Hermann Hornstein, names not usually associated with Oriental or Mediterranean Jews.

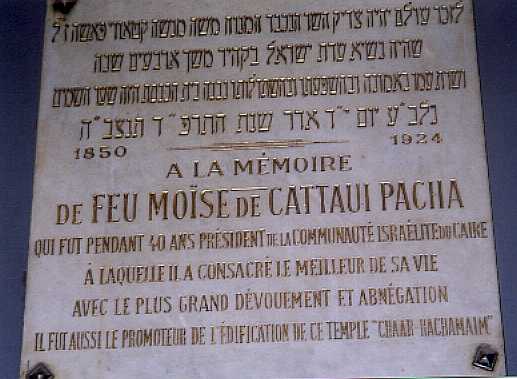

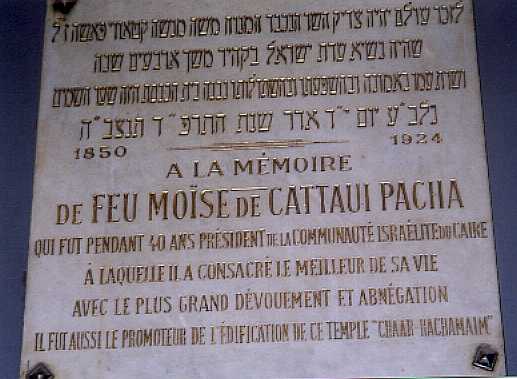

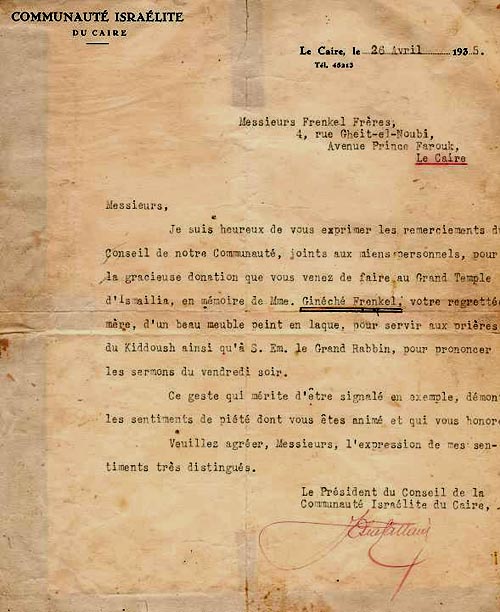

Other plaques on exhibit in the main hall and in the central courtyard evidence that Moussa Cattaui Pasha was commended "for 40 years of noble service as president of the Cairo Jewish Community and a promoter of Chaar Hachamaim." Two more recent plaques state that in September 1935 Elie Curiel donated funds for the creation of an "oratoire" and that five years later, Nathan Raphael Najar and his wife Leonie Jabes contributed towards the temple's restoration.

In fact, the temple's 1940 restoration would not have been the first one. From the Egyptian Gazette we learn how an in-house fire in 1922 resulted in the partial destruction of Chaar Hachamaim. And just as the president of the community showed up to inspect the damage a charred beam fell on the Pasha gravely injuring his shoulder.

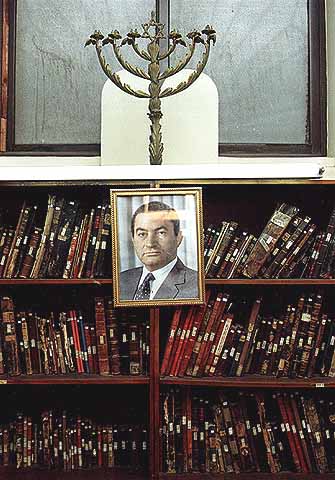

The temple's last restoration took place a decade ago coinciding with the 24 January 1989 opening of an adjacent Historical Jewish Studies library in what had previously been the temple's Wedding and Celebration Hall.

Notwithstanding a plaque proclaiming that a certain Zaky Mory was gabbay (temple functionary) between 1957-65 no mention is made anywhere of the highly respected Ottoman-born Grand Rabbi Haiim Nahum Effendi. He officiated at Chaar Hachamaim from 1922 until he passed away in 1961. Interestingly, a visiting assistant in the mid-1940s who may have conducted services at the Gates of Heaven was Rabbi Ovadia Yossef. Today, Yossef is the idolized spiritual guide of Shaas, a powerful religious party in Israel that carries with it the crucial parliamentary swing vote.

As the Jewish High Holidays approach, the Gates of Heaven will roll out the red carpet next September when Cairo's remaining Jewish worshipers congregate to celebrate the millennium's last Rosh Hashana (New Year) and perhaps to also wish a Happy Centennial to Cairo's only fully operating Synagogue.

The library at Chaar Hachamaim

Gineche Frenkle's pupitre then and now

|

Reader Comments |

From: albert bivas |

|

|

|

|