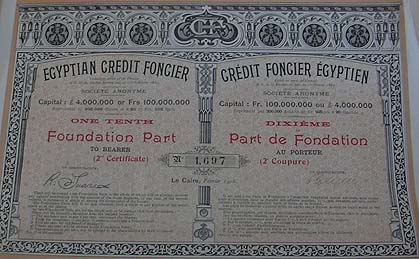

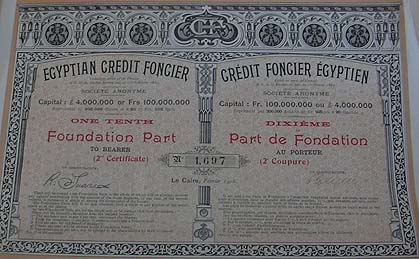

Credit Foncier Egyptien founding directors Karl Heinrich Beyerle (L) and Raphael Suares; 1905 bearer share certificate with Raphael Suares's signature

|

|

|

|

|

Cheers to our "talented" literature prize awardee. Your pain his gain !!!

|

|

|

EGY.COM - LANDMARKS - CAIRO - HELIOPOLIS

|

|

by Samir Raafat

The Egyptian Gazette, February 15, 1997

Credit Foncier's founders and shareholders were predominantly French or French-protected up until it was nationalized in the late 1950s.

On the other hand, the National Bank of Egypt was run as an exclusive British club during its first forty-seven years of existence. In fact, the creation of the National Bank was in greater part an effort by Egypt's British occupiers to break or circumvent France's hold over the country's banking system.

It was no coincidence that the Credit Foncier chose the corner plot on Manakh (later Abdel Khalek Sarwat Pasha) Street and Emad al-Din on which to erect its imposing Cairo headquarters in 1903-4. Originally, the area had been an extension the old hippodrome where so many races took place in the middle of the 19th century. In the 1860s, both the hippodrome and the outlying area were earmarked for urban development as part of Khedive Ismail's scheme to create the new Europeanized district of Ismailia.

An entire block of the newly traced district was picked up by two of modern Cairo's biggest land speculators: Mr. Karl Heinrich Beyerle and Mr. Raphael Menachem Suares. Both gentlemen were founding shareholders of the Credit Foncier Egyptien, which, at the time, had its main offices in Alexandria. And both had been bankers to Khedive Ismail at one time or another. In 1873 Beyerle represented Herman Oppenheimer & Co. in Egypt--the noted financial institution that would later play a capital role in bankrupting the Khedive.

Most of the commercial property surrounding the bank's proposed Cairo branch, including the semi-circled- shaped Cercle Risotto, still standing today, belonged to Suares, hence the name Rondpoint Suares. It was only in the early 1940s that the name of the roundabout changed to Mustafa Kamel; as though to indicate changing times, the name of the famous French-educated Ottoman-Egyptian nationalist replaced that of the wealthy Italo-Mediterranean Jewish capitalist. Both men, whose paths may never have crossed, made their fame or fortune in late 19th century Egypt.

The site located, it was now a choice of architects. Which one of the contenders was going be given the task of building the Cairo headquarters of Egypt's leading bank? Several names come up when researching the bank's history: Carlo Prampolini, Antonio Lasciac, Max Herz and Edward Matasek. All four were renowned architects and each had at one time or another, worked for the Egyptian government.

While it isn't exactly clear who exactly was the project's principal architect, one particular name that keeps coming up in contemporary references is that of Miksa "Max" Herz.

Born on 19 May 1856 in the Romanian town of Otlaka, Herz was the son of a tiller of the soil. After graduating from the school of architecture in Vienna, Herz visited Egypt in 1881 for the first time. The following year he joined the Egyptian service as an architect for the Department of Waqf (Endowment Authority) bringing him in close contacts in what would become his forte: Islamic architecture and mosques.

In 1888, Herz was nominated to the prestigious Comité de Conservation des Monuments de l'Art Arabe. Two years later, he succeeded Julius Franz Pasha as Director of the Islamic Art Preservation Committee. Herz was also responsible for putting together the Egyptian pavilion at the Chicago Universal Exhibition of 1892. That same year, he was asked to supervise the cataloguing of the contents of the National Museum for Islamic Art. The museum was re-inaugurated in 1903 with Herz at its head.

In 1895 Herz was made a 'Bey' and henceforth known as 'Herz Bey' until his elevation to 'Pasha' in 1910. But like all citizens of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, pashas notwithstanding, Herz was made to resign all his functions in 1914. England was at war with Germany and Austria, and Egypt had been unilaterally proclaimed a British Protectorate.

During his Egyptian career Herz Bey wrote about, was involved with, and responsible for, the restoration, design and creation of the following Islamic buildings: The Mosque of Sultan Hassan, the Rifai Mosque, and the Sultan Qalawun. Civil works in which he may have participated include: the Zogheb Villa which became the Danish Legation and the, the villa of St. Maurice (later the French Legation) both located in Cairo's Ismailia district, not too far from the Credit Foncier Egyptien.

Whether or not Herz gets singular credit for the design of the Credit Foncier building, it should nevertheless be listed and classified. This means no additions, subtractions or defacing of its original structure should be allowed. Moreover, any changes previously introduced, such as extra rooms on the roof, piping, or air condition holes etc. should be removed. The building's shell, its facade in particular, should be minutely restored in keeping with its formal design.

Meanwhile, the gilded interior should undergo an intensive refurbishment program bringing this bank to its former extravagant glory. This is an historic house and keeping it has to be the bank's priority. Perhaps the present owner could turn the building into a plush showcase exclusively for its executive offices, flushing out the rank and file and relocating them to more modern quarters. That is how it is done in other world banking centers: the palace for the head office and senior executives, and the modern office buildings for the other labor-intensive departments.

Luck is on our side for the present owner is the cash rich Arab International Bank, one of the very first fruits of Sadat's infitah policy.

The bank's chairman is Sadat's long time confidant and prime minister, Engineer Mustafa Khalil. A refined man and a connoisseur of the arts Khalil is sensitive enough to appreciate his headquarter's special character. Surely, he will spare no effort to restore one of Cairo's finer monuments to its former regal splendor setting an excellent precedent. And since he is a world traveler, Khalil need only check out how other cities are coping with their grand monuments and buildings.

A restoration effort that comes immediately to mind is how New York City is currently restoring its Grand Central Station turning what has often been called a dormitory for the homeless into one of the city's most famous landmarks. Both, the Arab International Bank building and Grand Central Station belong to that same generation of splendid fin de siècle buildings. Both aged badly, one from neglect in a city often on the verge of bankruptcy and the other because ever since the Credit Foncier was nationalized, the building endured several owners who often didn't appreciate its value.

Notes:

Subject:

Thank you for an excellent article

Date: Fri, 01 Jun 2001 01:56:30 -0500

From: Auburn User

I read your article regarding the Building of the Arab International Bank. It is really excellent, I hope more people will respect the

beautiful Egyptian heritage from extra commercialization and the running after more profit and more money regardless of any thing else. Thank you

for this this excellent article. Will you be kind enough to keep me informed regarding this issue and similar ones. All my contact information is giving below.

Warmest Regards,

Said Enlace

S.S.E.H.Elnashaie

Professor

Chemical Engineering Department

Auburn University , 230 Ross Hall ,

Auburn , AL 36849-5127 , USA

Subject: Your article

Date: Thu, 01 Jul 1999 15:35:53 -0700

From: Sam Badawi

I read your article regarding the Credit Foncier Egyptien building with great pleasure. It brought back memories of when, as a child back in

the early fifties, I used to visit my father at his office there. My father, Dr Helmi Bahgat Badawi, was the number three man, and the top

Egyptian, at the bank at the time. I would often be dropped off there by my mother while she did her shopping in town and used to wander all

over the building talking to the various employees.

Thanks for bringing back memories of a different, and much better, age.

|

|