|

egy.com suggests following articles

|

|

Several of my articles on Garden City were plagiarized word for word by novelist MEKKAWI SAID (winner of the Egyptian State price for literature!!!!) and re-published under his own name in a three-part series in El-Masry El-Youm daily in September 2015. Cheers to our "talented" literature prize awardee. Your pain his gain !!!

|

EGY.COM - LANDMARKS - CAIRO - HELIOPOLIS

75 South Audley Street

Above: First British occupant of Bute House: John Stuart Marquis of Bute

below: First Egyptian occupants: Abdel Aziz Izzet Pasha and Baheya Mansour Yegen (a granddaughter of Khedive Ismail and the niece of King Fouad)

portrait photos courtesy Sheila Wyze

EARLY OWNERS OF BUTE HOUSE

Not to be confused with that other Bute House, which is today the official residence of Scotandís First Minister situated in the heart of Edinburgh, the London Bute House is named after an unpopular 18th century Scottish nobleman who was British prime minister between May 1762 and April 1763).

John Stuart (1713-92) Third Earl of Bute lived and later died at Bute House aged 79. Perhaps unpopular with the British public yet to his credit it was John Stuart who advised on the foundation of Kew Gardens.

The Bute family are direct descendants of King Robert the Bruce whose daughter Marjorie married in 1315 Walter, the then "Steward of Bute". Their son, King Robert II of Scotland, thus became the first Stuart King. The Stuart name is derived from the hereditary office of "Steward of Bute" held by the family since 1157.

Flanked by South and Deanery Streets, Bute House fronts Mayfair's posh South Audley Street. The three-story building was originally laid out in 1736 by Edward Shepheard for John St. John (afterwards Viscount St. John of Battersea). In 1748 it was leased to Lady Margaret Watson (Dowager Lady Monson) for 220 pounds per annum. When he moved into the house in 1753, the Earl of Bute became the building's third occupant. Thereafter it would be known as Bute House.

Between 1812-19 the 4th Duke of Buccleuch (also Sixth Duke of Queensberry) lived there. He was succeeded by Lewis Hughes, MP, (afterwards Lord Dinorben) during whose occupancy part of the building burnt down in 1835.

Henri Louis Bischoffsheim (1828-1908) acquired the property in 1872. An art collector and banker, Bute House's new owner was also a relation of the greatest art collector of his day, Nathan Rothschild.

With his Viennese-born wife Clarissa, a daughter of Herr Bidderman, a Hapsburg court jeweler, Bischoffsheim supervised circa 1876 the installation of the famous "Allegory of Venus and Time" fresco on the Blue Drawing Room ceiling. This exquisite Venetian work by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo was accompanied by four roundels in grisaille. The forgotten Tiepolo paintings would be re-discovered in December 1964 when a connoisseur from the Louvre museum identified them for what they were... priceless masterpieces.

the fabulously wealthy Jewish banker Henry Bischoffsheim with wife Clarissa and daughter Amelia (Lady Fitzgerald)

below: masterpiece by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696-1770)

"Allegory with Venus and Time" fresco by Tiepolo that adorned the Louis XVI blue salon ceiling, sold in 1969 by an insolvent Egyptian government to London's National Gallery for an alleged sum of 300,000 pounds sterling

Like his relations the Hirsch, Goldschmidts, Sassoons and Rothschilds, Louis Bischoffsheim was a director of a famous Jewish banking-house carrying his name. Together the above played a pivotal role in Egypt's precarious finances during Khedive Ismail's debt-mounting years.

Following Bischoffsheim's death, Bute House passed on to his daughter Amelia Catherine wife of Anglo-Irish nobleman Sir Maurice Fitzgerald. She lived there until 1925.

BUTE HOUSE BECOMES EGYPTIAN PROPERTY

Al Ahram of 4 December 1925 reports that the Egyptian government represented by the National Bank (al-Ahli) formerly acquired Bute House for 90,000 English Pounds. Henceforth, and up to this day, No. 75 South Audley Street is the official seat of the Egyptian embassy in London. It was the King's policy to purchase prime properties in major capitals, hence the imposing Egyptian embassy residences in Washington, Paris, Rome and Athens. Neither was it a coincidence that Egypt's first senior diplomatic representatives to Paris, London and Washington were all related by marriage to the monarch. If Washington's Seifullah Youssri and London's Abdel Aziz Izzet were married to the King's nieces, Mahmoud Fakhry Pasha in Paris was married to the king's eldest daughter.

According to contemporary press reports, the Izzets were reluctant residents at Bute House, its purchase having taken place against the pasha's personal recommendation. On 5 December 1925, while holidaying in Switzerland, Izzet Pasha had sent the following telegram to Egypt's foreign minister Ahmed Ziwer Pasha (1864-1945):

I am surprised to see from the London papers a statement that the Egyptian Government intends to purchase Bute House for housing the Egyptian Legation. I see that it is my duty to repeat my remarks about that house which I made to Your Excellency when we last met in London. In my opinion the locality is not fitting for the Legation. The price is very high, the building is old and in no way suitable for the purpose in view.

Soon enough, Bute House became the topic of intensive deliberation in Parliament when on 21 August 1926 a number MPs grilled the incumbent foreign minister regarding Ziwer's unilateral action regarding the ill-fated purchase. Questions were also raised about costs, suitability and why the property was still in the name of three British aristocrats in lieu of the Kingdom of Egypt, especially since the National Bank of Egypt had already transferred the price in full. As it turned out this was a nominal circumvention of British Law which forbade foreign governments from owning British soil within the UK. Hence the three English gentlemen were acting as surrogates for the Egyptian government until the question of legal ownership could be resolved.

The heated debate took an entire parliamentary session. Luckily for him the former foreign minister was in one of Europeís fashionable thermal centers at the time.

Despite his declared reservations, Izzet Pasha was faced with a fait accompli and Bute House became his office and residence for the next few years. It was during his tenure that the Egyptian government commissioned Fernand Billeney to reconstruct its interior using Holland, Hannen & Cubitt as prime contractors. Whereas the ground floor was refurbished English-style, the first floor was remarkably Louis XVI; an arrangement that perfectly suited Bute House's first Egyptian resident.

The next Egyptian resident minister plenipotentiary at Bute House was Doctor Hafez Affifi Pasha who assumed his responsibilities in July 1930. According to an 11 January 1937 council of ministers decree we learn he received a salary of LE 3,000 per annum plus LE 5,000 in representation allowance. The same decree also allowed for a LE 2,000 provision for the purchase of new furniture.

In December 1934 Hassan Sabri Pasha replaced Doctor Hafez Afifi Pasha. Much appreciated by the British, Sabri would later become Egypt's Prime Minister. He was replaced by Hassan Nachat Pasha (1888-1969) at Bute House but this time around the new occupant was as a full-fledged ambassador.

As founder of Egypt's pro-palace Unionist Party, Nachat Pasha was considered too close to the king for comfort. Through the machinations of subsequent Wafd governments that wanted him out of the picture, Nachat Pasha was given the choice of several foreign postings that took him to Tehran, Madrid and later to bellicose Berlin.

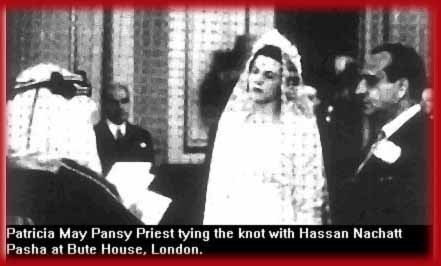

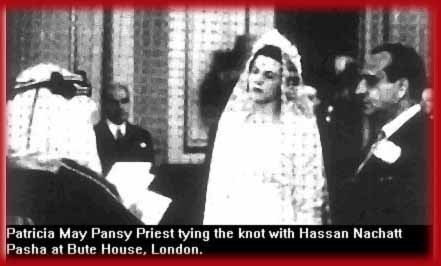

Recently widowed Nachat Pasha spent most of his UK years a bachelor. It was only towards the end of his tenure that he married Australian-born Patricia May Marsh, thirty-two years his junior. Marsh was the niece of General Robert Priest, honorary physician to Queen Elizabeth (better known today as the Queen Mom).

What the London press termed "the society wedding of the season," was celebrated on 24 October 1944, officiated by Sheik Hafez Wahba, an Egyptian teacher-cleric who found emplyment with the then-nascent Saudi diplomatic service.

The bridegroom's best man was exiled King Ahmed Zog of Albania; his wife Queen Geraldine Apponyi was matron of honor.

Having converted to Islam, Patricia May became Patricia-Zeinab. "Despite the war, everyone had a wonderful time!" she recalls 50 years later. "It was well known in London circles that Egyptís ambassador was a grand seigneur and lavish host. If rations and shortages characterized wartime England, Bute House never lacked good fare."

photo courtesy Patricia Nachat

But Nachat Pasha's stay at Bute House was not all happy celebrations. Quite the contrary! At first the Egyptian ambassador was suspected of harboring pro-Germanic sympathies. His detractors within the British establishment remarked he had gone bear-hunting in the woods outside Berlin with the Reichstag president, Herr Hermann Goering. Others resented the sleek Mercedes that Nachat Pasha proudly drove around London.

With time however, these and other reservations dissipated especially when Nachat Pasha repeatedly warned British cabinet members that Germany was preparing for an all-out war. Time proved him right.

Whereas in bubbling wartime Cairo, Sir Miles Lampson (later Baron Killearn; 1880-1964) and his much younger Italian bride Jacqueline Castellani, made the most of the 1940-1941 Christmas season, his opposite number in London was prey to deadly air raids by Germany's Luftwaffe.

On the evening of 28 December 1940, at around 18:30, Bute House received a direct hit from the German Luftwaffe with considerable damage done to the embassy's facade and basement. Luckily for "the boys"--a reference by Nachat Pasha to his younger staff--it was after working hours and none of the diplomatic staff were in the chancery.

That day, Nachat Pasha was weekending with his future in-laws at his Devonshire country house. It was therefore at 'Ferndale' that he learned from the Lady Almonder, head nurse of St. George's Hospital in London, that members of his embassy staff were in the emergency ward with serious injuries. The unlucky ones were some of the embassy's hired help: Miss Bonner the telephone operator, Miss Daisy the housemaid, and Sydney Lawrence the embassy's butler who had just completed 11 years of devoted service. Minor injuries were also sustained by the Isaac brothers; Egyptian Jews who served as embassy footmen.

Miss Bonner's bloody remains were found splattered all over the walls next to the telephone station. Ironically, she had once been engaged to a German. The war not only ended her idyllic courtship but it eventually ended her life. December 28 was the last time she would chirp into the phone "Grosvenor 2401, ha-llo".

Daisy had worked at Bute House for 20 years. She took great pride in her job caring for the embassy's beautiful linen all of which were embroidered with "F" in honor of Kings Fouad and Farouk. Her other passion was reading novels. Up until December 29 she had shunned bomb shelters despite the ambassador's admonitions. In fact, this was the first time she heeded his recommendation and taken refuge in the embassy bunker. A fatal advice!

If parts of Bute House's basement were seriously damaged, the embassy's garage and six cars, including the prize Mercedes, an American Studebaker and the economical embassy Austin, were safe. Not as lucky was the embassy's well-stocked wine cellar. The house guards and firemen lost no time helping themselves to Nachat Pasha's prewar vintage. By the time the "all-clear" sounded, half of the rescuers were already drunk.

Restoring Bute House to its former state was no easy task for contractor Richard "Dicky" Thomas. Ever since it became Egyptian government property, this was the second time a major major upheaval was done to the listed building

Unable to operate in what was now an "out of combat" embassy, Nachat Pasha moved into a large suite at the neighboring Dorchester Hotel where he remained for the next 13 months. He returned on 11 February 1942, in time for King Farouk's 22nd birthday celebrations. On that occasion, the Royal Egyptian Embassy gave one of London's greatest wartime bashes.

Things would never be the same again at Bute House after Nachat Pasha's departure. Its greatest days were over. Henceforth it would become 'just another embassy'.

February 2009 occupant of Bute House presenting credentials to HM Queen Elizabeth II at Buckingham Palace

Ambassador Hatem A. Seifelnasr

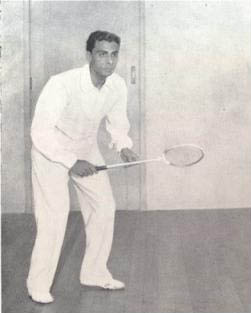

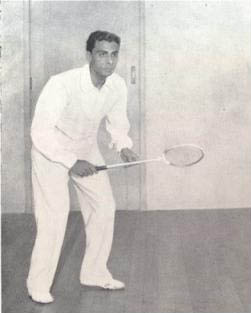

Ambassador Abdel Fattah Amr Pasha winner of the British Open championship six straight times, from 1933 through 1938

Notes:

- Mahmoud Fakhry Pasha, Egypt's first ambassador to France (with title of minister) was married to Princess Fawkia, eldest daughter of King Fouad. Fakhry Pasha purchased Villa (Jules)Ephrussi (scion of a wealthy Odessa family related to the Rothschilds through marriage), which became the Egyptian Ambassador's residence at No. 2 Place des Etats Unies.

- Seifullah Youssri Pasha, Egypt's first ambassador to the USA (with title of minister) was married to Princess Zeinab Hilmi whose father, Prince Ibrahim Hilmi was King Fouad's brother. The historic Joseph Beale House on Massachusetts Avenue was purchased shortly after.

- Egypt's purchased its US legation in Washington DC for LE 15,000 in April/May 1945.

- Aziz Izzet Pasha, Egypt's first ambassador to the UK (with title of minister) was married to Baheya Mansour Yegen, whose mother Tewhida Ismail was King Fouad's sister.

- Hassan Nachat Pasha was succeeded in London by Oxonian Abdel Fattah Amr Pasha, a sometime squash world champion.

- A bankrupt Egyptian government sold the Tiepolo fresco to London's National Gallery in 1969 for an undisclosed sum.

- In 1930 a descendant of Lord Bute built El Minzah Hotel in Tangiers.

summer 1937: King Farouk at the Royal Egyptian Club off Curzon street

Shortly after Bute House was purchased, the Egyptian government acquired from a Jewish banker part of a nearby block consisting of semi-detached town houses. Located at the corner of Chesterfield Gardens and Curzon Street, the property was set aside as the "Royal Egyptian Club", a place where resident and visiting Egyptians could meet, dine, debate and attend to private businesses.

Emulating contemporary local men-only clubs, No 4 Chesterfield Gardens acquired over the years a wonderful library, objets d'art and considerable memorabilia courtesy of prominent Egyptians with strong connections to the UK.

The building also served as a London base for young Prince (later king) Farouk's brief 1936 passage in the UK during his last school year. With its wonderful halls and reception rooms the "Egyptian Club" hosted many cultural and academic events eventually becoming a fully-fledged Egyptian Cultural Center reporting directly to the Ministry of Higher Education which oversees both its staff and budget.

Shortly after the Egyptian Embassy sold the Tiepolo fresco there was talk of selling No. 4 Chesterfield Gardens. This project although muted at the time, resurfaced over the years again and again. According to Ali Shamseldine who was cultural attache/counsellor back in the early 1990s, titles and deeds to the property were hard to come by since no one knew which Egyptian administrative body held them.

pre-1952 reception at the "Royal Egyptian Club" (photo courtesy Amr Badredine)

Subject: Bute House, South Audley Street, London

Date: Sun, 04 Jul 2004 19:25:55 +0100

From: Ed Crutchley

I was interested to see your web page on Bute House.

My family have the keys supposedly to a vault in a Catholic Chapel where Lord Bute and his daughter-in-law Louisa Stuart were buried. We believe we are related to Bute's son, Gen. Sir Charles Stuart, and have portraits of him and his wife as well.

We had always understood that the chapel had been destroyed by a bomb during WW2, and I see you mention a bomb that landed on Bute House on 28th December 1940 at 18.30, which makes our story all the more likely.

Are you able to tell me anything more about a vault? We would be most interested to hear from you.

Email your thoughts to egy.com

© Copyright Samir Raafat

Any commercial use of the data and/or content is prohibited

reproduction of photos from this website strictly forbidden

touts droits reserves