Samir Raafat

Jordan Star and other publications, April 23, 1998

Djehane al-Husseini, David Govrin

|

|

|

|

|

|

EGY.COM - JUDAICA

|

|

Samir Raafat

Jordan Star and other publications, April 23, 1998

Djehane al-Husseini, David Govrin

In mid-March I accompanied a 21-member delegation of Cairo-based foreign journalists into the heart of the Arab-Israeli conflict. We visited in turn Gaza, East Jerusalem and the West Bank. During our four-day tour we met Yasser Arafat, Saeb Erekat, Nabil Shaath, Feisal Husseini and a host of Palestinian mayors presiding over bantustinettes a term repeatedly used by Shaath when describing the West Bank’s self-rule regions, a motley scattering of towns and villages sandwiched between Israeli settlements. The latter loom large on the surrounding hilltops like giant lookout towers.

In mid-March I accompanied a 21-member delegation of Cairo-based foreign journalists into the heart of the Arab-Israeli conflict. We visited in turn Gaza, East Jerusalem and the West Bank. During our four-day tour we met Yasser Arafat, Saeb Erekat, Nabil Shaath, Feisal Husseini and a host of Palestinian mayors presiding over bantustinettes a term repeatedly used by Shaath when describing the West Bank’s self-rule regions, a motley scattering of towns and villages sandwiched between Israeli settlements. The latter loom large on the surrounding hilltops like giant lookout towers.

This was my second visit to Israel, the first having taken place in November 1994 when I was invited by Tel Aviv University's Kaplan Chair to lecture on my book dealing with the Cairo suburb of Maadi, home to a multitude of Jews between 1910 and 1963.

My treatment at border control this time was noticeably different. Whereas in 1994 I was received like visiting royalty, this time it was a polemical security drill. None of the co-ed Uzi-totting Israeli interlocutors at Rafah or Eilat looked over 24, which perhaps accounts for their youthful arrogance. To the soldiers' credit however, they treated us with the same icy indifference irrespective of our individual nationalities. It didn't matter to them if one was 26 or 75. Nor did the weather matter, for at the Erez checkpoint (between Gaza and Israel) we were left out in torrential rain as two macho IDF soldiers checked our passports and luggage from the confines of their weather-proof kiosk. We were supposedly in the VIP lane!

It didn't take much traveling by private bus whether in Gaza or the West Bank to realize the short distances that separate the different population centers. While Palestinians and Israelis live in close proximity to one another their relations are anything but neighborly. The city of Jerusalem best exemplifies this explosive situation.

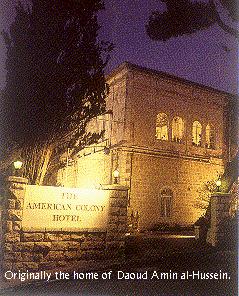

Yet it was over dinner at East Jerusalem's historical American Colony Hotel that I came face to face with the psychological and historical chasm that separates the warring neighbors.

Upon hearing I was in Jerusalem, David, a former Israeli diplomat in Egypt, now serving in his country's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, dropped by the hotel. I knew David when he lived in Maadi, the favored place of residence for Israeli diplomats serving in Cairo.

Because of the raging snowstorm, I suggested we have dinner in the hotel. I was told the American Colony had some of the best fare in town. Just as we were about to order we were joined by my travel colleague Djehane, the tall brunette correspondent for Al-Hayat, a London-based Arabic-language daily. She sat down thinking the blond blue-eyed David was a Westerner staying at the hotel. And if David thought Djehane was an attractive Sabra of Oriental Jewish stock, he didn't say. But the thought could easily have crossed his mind.

To avoid what I thought might turn into an embarrassing situation, I spelled out during the introductions exactly who did what. Both my dinner partners belonged to the urbane, trendy, yuppie thirty-something generation. They were well-mannered and articulate. Under any other circumstances they could have started a fast friendship. After formal greetings were exchanged, by tacit understanding we all agreed to disagree.

DJEHANE AL HUSSEINI

David learned that Djehane was Palestinian-born. She belonged to one of the oldest Jerusalemite and Jaffa families, right up there with the Husseinis, Khalidis, Nashashibis, Dajanis and Faroukis whose uninterrupted presence in Palestine goes back a millennium and more. In fact, early this century, the beautiful American Colony Hotel had belonged to one of Djehane's ancestors before selling it to missionaries from the United States. Djehane's parents were from what in 1948 became West Jerusalem. They were forced to flee during the war that followed the creation of the State of Israel. A "transfer" system over which they had no control had begun÷a polite term for ethnic cleansing. Arabs were no longer welcome in their own land, and Djehane's parents were among its first victims.

Like many of her displaced compatriots, Djehane acquired a Jordanian passport÷the West Bank and East Jerusalem having been incorporated into the Kingdom of Transjordan between 1948 and June 1967. While some within her family hold U.N. Palestinian refugee documents, those from the Gaza region still have Egyptian-issued Laissez-Passers. There are also her less fortunate West Bank relations who cannot move from one Bantustinette to the other without the tell-all Israeli-issued magnetic card. These are constantly updated reflecting any behavioural or physical changes. If for instance a reference to stone throwing during intifada appears on screen you can forget about a permit to travel between Gaza and the West Bank or vice-versa÷a permit takes several weeks to obtain. There are of course Djehane's old Palestinians uncles who became Arab-Israeli citizens despite themselves. They had not fled with the others following the "transfer" system. And there are the Palestinian rejects now living in some accursed Lebanese or Syrian refugee camps. Djehane's relations were many and all over.

The Meaning of Diaspora

Like David's parents, Djehane knew the meaning of diaspora. Following the June 1967 war, Amman and Cairo became Djehane's adopted homes. It was impossible to return to East Jerusalem, specially since her father had been a PLO diplomat representing the little which had remained of the disputed land. It was only after Jordan signed a peace treaty with Israel in 1994 that she was allowed to "visit." But only as a tourist. Like other Palestinians in the diaspora, Djehane has to undergo the third degree whenever she shows up at Israeli ports of entry: "Do you know or have any relations in Israel (meaning Israel and the occupied territories)? Did you bring them gifts? Did anyone pack your bag for you? How long do you plan to visit? Where will you travel when inside Israel?"

Did Djehane believe that Israeli-born David had a right to be in 'Palestine'?

Deafening silence.

DAVID GOVRIN

In return Djehane learned that David, not unlike like herself, was the offspring of a former diplomat. He was born in former Palestine and now lives lives in Mevaseret Tzion. David's parents were immigrants from Eastern Europe where their forebears had lived for as long as they could remember. Which is perhaps why David's father Yosef Govrin (born Gurvitz) returned to Mittle-Europa but this time as Israel's ambassador to Roumania and Austria.

If members of David's extended family were victims of the Holocaust, being of secular nature religious persuasion had little to do with their subsequent arrival in Palestine. Yet whenever asked why they chose Tel Aviv over New York, which has one of the largest concentration of Jews, they will tell you about exercising their divine right of return. A right that if you are a Jew has no statutes of limitation whether we are talking 20 or 2,020 years! This was their Promised Land!

It was during his military service that David met his wife Noya Cikurel, whose parents came from Turkey and Eastern Europe. Confirmed Zionists, David and Noya are still on military reserve. With two young sons to raise (Tomer & Amit), both want to live in peace. A peace undisturbed by Hamas bombs or Jewish settler violence.

While serving as a diplomat in Egypt÷the first Arab country to sign a peace treaty with Israel almost 20 years ago÷David, a straightforward and welcoming person, did his best to promote bilateral relations. It wasn't easy. A few months after his arrival in Cairo, Hamas suicide bombs went off in Tel Aviv and its suburbs killing civilian commuters. This was followed by Yitzhak Rabin's assassination by a Jewish extremist followed by a second spate of suicide bombs and the subsequent fall of the Labor government. A Likud-led coalition, the trashing of the Oslo accords and the virtual breakdown of peace talks between Arafat and Netanyahu affected relations between Egypt and Israel. The MENA economic conference, which David and others of his calling had worked on relentlessly, fell apart. In Cairo fewer and fewer people were returning David's calls. Invitations from Egyptian counterparts dried up. Soon enough, a city of 15 million had become a lonely place. It was a disillusioned David who returned home last summer.

Did David believe in Djehane's right of return to 'Israel'?

Shattering stillness!

IMPASSE

The conversation got nowhere. The only item we seemed to agree upon was the good food and the unpredictable weather. It was still snowing outside when we ordered dessert. In the background we could hear church bells and the calls of a muezzin.

And then the check arrived.

Suddenly, as though by magic, we were all Middle-Easterners through and through. Instinct and Middle Eastern hospitality prevailed for a brief moment. Everyone insisted on paying for the others. None of that separate check business common in the West.

But even this collective outburst of cordiality was too good to last. David, spurred on by spontaneity, insisted that because we were in his country ("intu fi baladi"), we were therefore his guests.

"East Jerusalem is not part of Israel yet!" interjected an anguished Djehane.

The magic of the moment quickly vanished. The brief flash of good spirits had been dampened. A distraught Djehane felt that David and myself were both visitors to her birth-city and guests in her ancestral home. Meanwhile, David, who had acted out of spontaneity, believed÷like all Israelis÷that Greater Jerusalem was his capital irrespective of U.N. resolutions and world proclamations to the contrary.

Each one paid for himself.

I then realized the true nature of the chasm when David later explained to me that as an adult this was the first time he had ever socialized with a Palestinian away from the negotiating table.

And they have been neighbors all these years.

"Cold & Worry" by Ismail Shammout (1931-2006) exhibited in Cairo in 1952 depicting Palestinian refugees in 1948-49

private collection

|

Reader Comments |

|

Subject: Egy Articles Date: Thu, 18 Jun 1998 11:56:10 -0700 From: Leila Abu-Saba MacLeod I read your account of the dinner in Jerusalem with the Israeli diplomat and the Palestinian journalist. This was a touching, uncomfortable moment and you told the story well. I really appreciate how a simple dinner check can blow open history, pain, statelessness, sorrow. Thanks again for your reporting and your research - I will check the Gazette online more frequently (hadn't looked at it since late winter) and follow your work. Sincerely yours, Leila Abu-Saba Berkeley, California, USA Subject: Who will settle the check? Date: Wed, 20 May 1998 09:45:15 PDT From: kassema jones I just finished reading your article " who will settle the check?" I really admired your style, your tone and you sarcasm. so Keep up your momentum and the good work. Subject: WHO WILL SETTLE THE CHECK? Date: Sat, 16 May 1998 21:24:15 -0400 From: Theodor Feibel, Photographer I very much enjoyed your article. I hope many others will have a chance to as well. All the best, PS: You gingerly touch on a number of, shall we call them "difficult topics", in your above mentioned writing. At this point how close do you believe Palestinian Arabs are to accepting a peaceful coexistence with Israel, and how close do you think Israelis are to viewing Arab Palestinians as peaceful neighbors? (I imagine that some of those considerations play a role in the security decisions on all sides). In fact, let's open the question to another level of scale. How close are we to a time that Anti-Israel sentiment is no longer popular (and a potential political platform) for a political figure in the Arab World?

|

|

|

|

|