|

|

|

|

|

|

EGY.COM - HISTORICA

|

|

Samir Raafat

The Egyptian Mail, Saturday October 26, 1996

This article was illegally and shamefully copied (plagiarized) in its entirety by CodeFez a so-called IT management company

IT WAS DURING the reign of Ottoman Sultan Mahmud Khan II (1808-39) that European code of dress gradually replaced the traditional robes worn by members of the sultanic court. The change in costume was soon emulated by senior civil servants followed by members of the ruling intelligentsia and the emancipated classes throughout the Empire.

While European dress code gradually gained appeal, bowlers with their great brims and the French beret never stood a chance. They did not conform with customs and religions of the east. In their stead the Sultan issued a firman (Imperial decree) that the checheya headgear in its modified form would become part of the formal attire irrespective of his subjects' religious sects or millets.

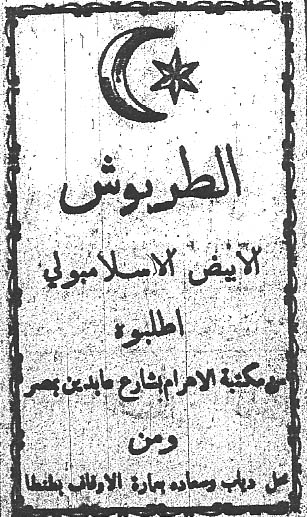

The checheya had many names and shapes. While in Istanbul it was called 'fez' or 'phecy' in Egypt it was called 'tarboosh' (pronounced tar-boosh) a corrupted derivative from the Persian words 'sar' meaning head and 'poosh' meaning cover. It was basically a brimless, cone-shaped, flat-topped hat made of felt. Originating in Fez, Morocco, the earliest variety of the tar-boosh was in the form of a bonnet with a long turban wound around it which could be white, red or black. When it was adopted in Istanbul the bonnet was modified. At first it was rounded then, some time later, lengthened and subsequently shortened. At some point the turban was eliminated and the color of the checheya stuck to red.

Towards the latter part of his reign Egypt's Mohammed Ali incorporated the Greek version of the fez as part of the military uniform. All officers, regardless of rank or nationality were required to wear it. Soldiers were issued two fez's a year with their uniforms. This meant the Viceroy had to import almost 500,000 fez's annually to satisfy his growing army's needs, which is probably why he issued a boyourli (viceregal firman) to his chief of district Mohammed Aga, residing in the town of Fawah, to immediately commence plans for the local manufacture of taboushes.

The first Egyptian-made tarboosh appeared on the market in 1825. By 1837 Egypt produced 720 per day in the province of Gharbieh alone. But when the state economy floundered during Khedive Ismail's reign, the tarboosh had to be imported. European manufacturers quickly multiplied their production lines especially since the 'Fez' had also become part of the Bosniak regiments in the Austro-Hungary army (up until 1918). Not surprising therefore that Austria was the biggest tarboosh producer in Europe.

Until it went bankrupt in the 1970s the tarboosh manufacturing firm of "HABIG Und Sohne" operated out of two adjacent buildings at Frankenbergasse No. 9 in Vienna's 4th district just minutes from St.Stephan's Cathedral. After WW-I and the subsequent demise of the Ottoman Empire, Egypt became Habig's single most important customer. Yet in order to survive HABIG was obliged to produce English top-hats as well, which later became the company's main source of revenue. The vestiges of this tarboosh manufacturing company were still in evidence when the buildings were renovated five years ago and when moulds used in order to press the 'fez' were found in the building's basement.

It was during the reign of King Fouad that a 'piaster' fund-raising scheme was launched and the proceeds invested in a tarboosh factory. By 1943, there were 14 tarboosh retailers in Cairo, four in Alexandria and one each in Tanta and Simbelawain. By then the tarboosh was once again modified to suit the fashion. While in Viceroy Ibrahim's time it had been a la Greque as evidenced by his statue in Opera Square, it became a la turc during Khedive Ismail's, much longer and almost covering the ears. During the reigns of Sultan Hussein and King Fouad, it was changed to its final shape and size, well above the ears as seen on the minted coins of that period.

Just like national flags, the tarboosh had become e national emblem. It was de rigeur at the Egyptian court, the civil service, the army and the police. Some officers wore it with a dashing slant, silken tassel flying in the breeze. Crown Prince Mohammed Ali Tewfik wore it in a manner defying gravity, looking like it was about to topple over at any moment. Others wore it as though it were a column sweating profusely beneath it. Its shape was described in a 1937 English editorial as esthetically and basically inferior to European hats. "The practical advantages that the hat has over the tarboosh is that the tarboosh offers very little defense against the sun; its long chimney-pot length makes it a convenient victim of any random gust of wind, and in time of rain it has to be mollycoddled and swathed in its owner's handkerchief in case it should come to harm."

THE SECOND TARBOOSH CRISIS

Tarbooshes were also worn by Egyptian diplomats abroad. This requirement almost caused the breakdown of relations between Egypt and Turkey when, on the occasion of the 9th anniversary of the proclamation of the Turkish republic (29 October 1932), Abdel Malek Hamza Bey, Egypt's envoy to Ankara, appeared at the Ankara Palace Hotel wearing his tarboosh.

Present at the hotel was Turkey's strongman, Ghazi Mustafa Kemal. (It was when the Surname Law was adopted in Turkey in 193 4 that the national parliament gave him the name "Ataturk" meaning father of the Turks.)

In his quest for a Yeni Turan or a 'new society', Mustafa Kemal decreed several laws which aimed at changing the norms and traditions of his country. For instance, in October 1928, he decreed that the capital move from Istanbul to Ankara. In November he proclaimed the Arabic script be changed to the Latin alphabet, a measure successfully adopted despite momentous challenges from the more traditional elements of society. Also by decree, the temenah a form of greeting where one touches one's forehead, lips and heart with the tips of his fingers, once the symbol of imperial obeisance, was no more. It would be substituted with a simple handshake.

Other drastic measures meant to bring Turkey in step with western culture included the outlaw of the bewitching yashmak and the eradication of the ferraji mantle, the bournous and the gandourah. European style of dress had come to displace the sherwals, the shalwahs and the baggy jodhpurs. Turbans and fashionable European hats replaced the veil. Mustafa Kemal was offering women their freedom.

Yet what was considered a most radical reform was the 1926 parliamentary decree abolishing the fez. Henceforth, the Ghazi forbade its appearance anywhere within his new secular state. To Mustafa Kemal, the fez and the veil were signs of backwardness, inferiority and religious fanaticism. Whereas in Turkey's not so distant past, anyone sporting a hat other than a fez was considered a Giaour (stranger or one belonging another faith and mode of life) now, western hats had become the rage. To encourage his people to turn away from the fez and adopt the western hat, the Ghazi would appear in public wearing different European headgear. With the power of law, the situation had now been irrevocably reversed.

So it must have been quite appalling for the supreme leader on his Republican Day celebrations to espie a red tarboosh bobbing about the crowded banquet hall. Unknown to him was that it belonged to Abdel Malek Hamza Bey, Egypt's fiery diplomatic envoy to Turkey.

Aiming to please their leader, Turkish protocol officials accosted the unsuspecting tarboosh wearer and advised him to remove it for fear of soliciting the Ghazi's wrath. Following a brief exchange between the Egyptian envoy and his Turkish counterparts from the foreign office, Abdel Malek Hamza Bey refused to comply with his hosts' requests arguing that his tarboosh formed an integral part of his national attire. Having made his point, he promptly took leave from the celebrations.

Once the reason for Abdel Malek Hamza's precipitated departure was made public, the press in both countries had a field day. Not to be outdone, the Daily Herald in London ran hair-raising columns on the subject detailing how the Egyptians felt insulted and how the Turks had countered that since the Egyptian minister had received a personal apology from the Ghazi, no offense had been done. And hadn't the Turkish foreign minister, Tewfic Rushdi Bey, declared that the Ankara Government did not consider it necessary to tender an apology on the grounds that Egypt's dignity was not touched at all; that the Egyptian Government must consider this incident as closed!

With a lot of restrain on both sides and despite the Daily Herald's malefic efforts, the diplomatic incident passed and relations between Egypt and Turkey were maintained for another twenty years--almost as long as the survival of the tarboosh itself.

In 1952, not unlike like the pashas and beys who proudly wore them, tarbooshes became history in Egypt, when the new republican government abolished the official headwear. In an unrelated incident, relations with Turkey were broken off.

As this century comes to a close, tarbooshes and top hats have become relics of the past and can only be found in masquerades, fancy dress balls and in one or two wayward freemason lodges. Wherever else you go, you will find multicolored baseball caps instead.

But what of the FIRST Tarboosh crisis? Well, that's another story but nevertheless here's a snippet to wet your appetite.

When Austria attacked Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1908, encouraging Greece and Bulgaria to secede from the Ottoman Empire, calls were heard across Turkey and its vassals to boycott all Austrian products among them the importation of tarbooshes manufactured in Vienna.

read also essay which appeared in 2003 (seven years after above article) by Yunan Labib Rizk of al-Ahram

|

|

|

|