QUEEN FOR A DAY

by Samir Raafat

AHRAM WEEKLY, October 6, 1994

Countess May von Torok in her youth and prime

|

|

|

|

|

|

EGY.COM - HISTORICA

|

|

by Samir Raafat

AHRAM WEEKLY, October 6, 1994

Countess May von Torok in her youth and prime

When Khedive Ismail Pasha went into regal exile in 1879 he took with him the last court harem. Gone forever were the stable of concubines and the daunting buyuk, ortangi and cucuk hanems (first, middle and third consorts). Also gone was the regiment of aghas (eunuchs) whose primary task was to keep harem affairs in order.

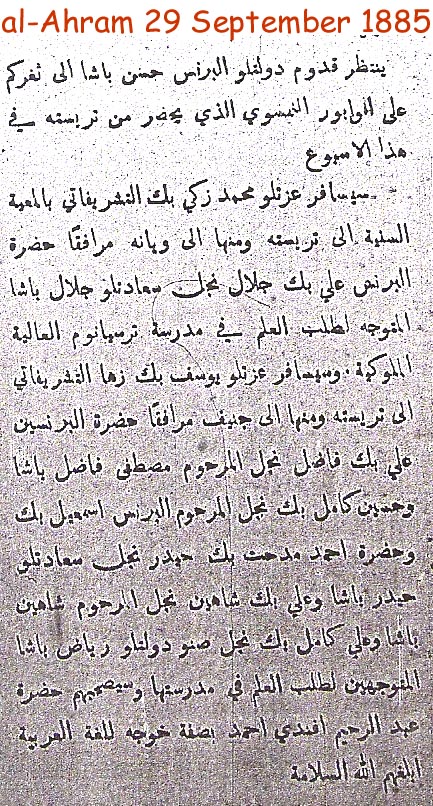

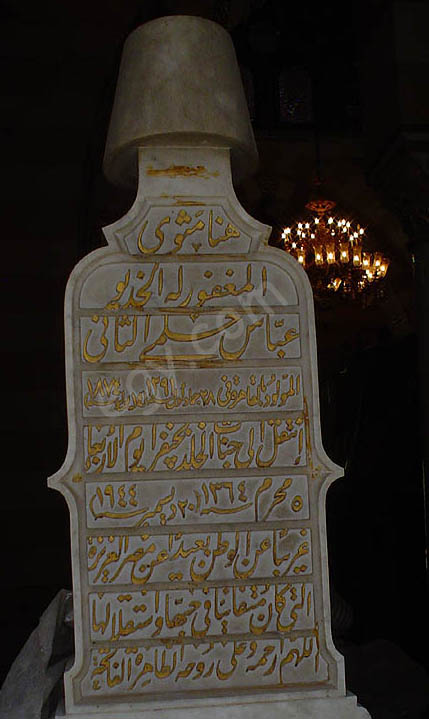

Since Ismail, Egyptian rulers starting with Khedive Tewfik contracted monogamous marriages consistent with modern day and age. Whereas Sultan Hussein, King Fouad, King Farouk and later, President Anwar al-Sadat, found it necessary to divorce and remarry, Khedive Abbas Hilmy II kept on an almost secret wife. Little is known of her except for a brief mention in al-Mussawar's special issue of 1938 and the Egyptian Gazette of 21 December 1944.

Estranged from his first wife Ekbal Hanem a former slave in his mother's household, Abbas Hilmy entered into a passionate romance with a beautiful Hungarian countess. Although the date of their morganatic marriage remains uncertain, we know however that during the last four years of their relationship, the countess was the khedive's legally wedded second wife. Their story, although not unusual, deserves to be retold for it combines all the elements that make for an interesting saga: romance, majesty, exile and adventure.

Even as she came into this world in Philadelphia (USA) on 15 June 1877, May Torok von Szendro's parent's marriage was coming to a close. Her mother, born Sofie Countess Vetter von der Lilie, was in hot pursuit of Hungarian inventor Theodor Puskas, a close collaborator of Thomas Alva Edison. In fact, in some Hungarian circles it is said May was actually the biological daughter of Puskas and therefore had no right to the title of countess!

It was as Edison's representative in Europe, that Puskas introduced the 'tele-phone' in the 1878 Paris World Exhibition. Accompanying him at this landmark event were Countess Sofie and her one year old daughter. When her divorce was finalized four years later, Sofie married Puskas in Westminster (Middlesex), England.

May Torok von Szendro spent most of her youth at Wassen Castle South of Graz, Austria. At age 12, she allegedly wrote short articles for various journals and played the piano. At 15, she had her own apartment in Graz. Although she never went to school, her elder brother Count Josef Torok von Szendro (1873-98), following Austrian tradition, was enrolled at the Theresianum, Vienna's famous academy patronized by Habsburg princes and scions of European, Egyptian, Ottoman and Oriental aristocracy. It was there that Count Josef befriended Abbas Bey, an Egyptian prince one year his junior.

Countess Torok first laid eyes on her future husband during one of her infrequent visits to Josef. She describes the event in her memoirs as follows: "Abbas Bey lived in a separate apartment in the Theresianum together with an Arab Sheik and a Turkish teacher, presumably so he would not forget his Quran and two mother tongues."

The countess met the Egyptian prince twice during that period, when Josef introduced his sister to the "shy, blonde, grayish-blue-eyed Abbas" and the following day at a ball given by the Academy.

A little more than a year before Count Josef's graduation, his princely friend was summoned suddenly to Egypt. A telegram had arrived announcing that Khedive Tewfik (1852-92) had died in his house in Helwan south of Cairo at 07:17 on 7 January 1892. Egypt's heir apparent, not yet 18 (b. Alexandria 14 July 1874), was expected in Egypt post haste.

Several years passed before Countess Torok met Abbas Bey again. By that time he was a husband, a father of four and more importantly, Khedive of Egypt. The meeting took place in France in June of 1900. Countess May was in Paris visiting her mother and stepfather, and the khedive was passing through on his way to London.

"After several years I met the young ruler again, this time in Paris. I was coming from the flower market at La Madeleine, arms full of roses, and entered the hall of the Grand Hotel where I was to meet a girlfriend. As I proceeded to look for her, the young khedive appeared in front of me. His face had matured but his grayish-blue eyes had the same indiscernible twinkle, as if the sun of Egypt radiated therefrom. I was completely startled, my roses fell to the ground, and we both smiled. The first word he said to me was 'In Egypt the roses are more beautiful'."

If one were to believe Countess May's memoirs, the Khedive was immediately smitten with the countess and wasted no time initiating a short but passionate correspondence followed by an invitation for the countess to visit Egypt.

At the port of Alexandria, Countess May was met by Friedrich von Thurneyssen Pasha, the Khedive's Austrian Master of the Horse. The visit developed into a long romance culminating into a secret marriage contracted in Alexandria's Montazah Palace witnessed by two sheiks. It would be years later before an official marriage took lace on 28 February 1910, with the Grand Mufti of Egypt officiating. Henceforth, Countess Torok was listed in the Gotha (peerage) handbook of nobility as Princess Djavidan Hanem, wife of the Khedive of Egypt.

But was she truly the wife of Egypt's monarch?

The Khedive’s affair with Countess May quickly became the subject of gossip within Cairo's foreign community. On the 27th of July 1910, William Hayter, a minor English administrator in the Egyptian government writes to his wife in England telling her, "The Khedive is having a hell of a time with his family in Constantinople. The Grand Cadi (Sheikh-el-Islam) absolutely refuses to recognize the ex-Countess, his new wife, unless she will appear before the Cadi and publicly repent of her sins and swear on the Koran to lead a clean life. She is treated in Turkey simply as a concubine. The Khedive Mere has announced that if he brings her back to Egypt she will make an open scandal. He is ruining himself all round over this woman who came off the streets of Vienna and was married by an old count in his dotage. She then picked H.H. and has stuck to him like a burr ever since. He knows what a bad ‘un she is, but he is infatuated and can’t get rid of her. She used to dress up as a boy and pervade the Palace of Koubbeh under the name of Ali Bey." ["A Late Beginner" by Priscilla Napier, 1966]

In fact, a few months before the above letter was penned by the gossipy English administrator, the khedive had already legalized his marriage to the Countess. But it must have been done in the utmost discretion since the press also seemed in the dark.

On 15 September 1909, six months before the official marriage was publicized, an article in the Egyptian Gazette, credited to the Washington Star in the United States, talks of the khedive's exemplary married life. "Khedive Opposes Polygamy: Has Only One Wife..." reads the title while the opening paragraph starts with famous last words "In the middle of the day, the ruler of Egypt lunches with the only woman who has ever sustained to him the relationship of wife".

Later on the article hails "The pious ruler" who seems "To have set his face firmly against the plurality of wives that is the vogue among the wealthier of his subjects."

The article was obviously referring to the khedive's Moslem wife, the mother of his six children. As though a deliberate plant meant to embarrass the Khedive, there was no mention in the article of his second marriage or of Countess May.

One cannot help wondering if the article's timing had anything to do with the worsening relations between the Khedive and Egypt's military occupiers. For it was known to everyone that the real ruler of Egypt since 1882 was the British pro-consul. Could the article therefore have been part of a ploy to undermine the pro-Germanic Abbas Hilmi II?

To the British it seemed like the Khedive's official household was infested with Austro-Hungarian and German officials. While the deputy chief of staff was a Baron Hugo von Fleischhacker Bey his ecuyer was Friedrich von Thurneyssen Pasha. The Khedive's private physicians were Anton Kautzky Bey and Dr. Bruno Bitter. His pharmacist and dentist were Josef Bilinsky Bey and Henriette Hornik respectively. His chief architect Anton Lasciac Bey and his baker were both Austro-Hungarian subjects.

As though the combined Germanic sway were not enough, now the Khedive was besotted with an Austro-Hungarian Countess.

In order to preempt further rumblings Countess May converted to Islam in the presence of the Grand Mufti. For some unknown reason or perhaps due to her parents' liberal temperament, she had never been baptized.

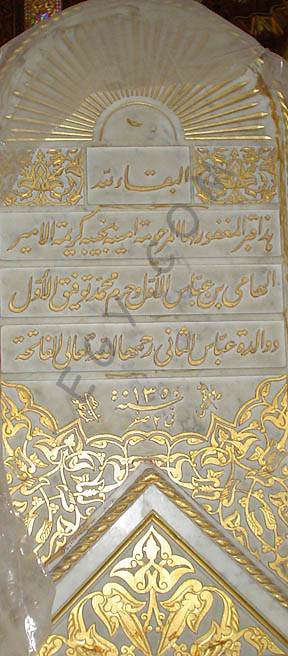

Countess May's conversion coincided with Abbas Hilmi's visit to Mecca which may account for her adopting a new Moslem name. At first she called herself Zubeida bint Abdallah. That was soon changed to the more courtly Djavidan. Since neither sheik or ulam accepted to tutor a member of the opposite sex, her teacher of the Quran was the famous Swiss Islamist, Hess von Wyss.

When in Cairo Countess May lived in the Khedivial domain of Mostorod, north east of the nation's capital. The rest of the time the countess accompanied the khedive on his travels to Turkey and Europe as well as inside Egypt. By virtue of this proximity heretofore unknown in Ottoman courts, Countess May had a not insignificant influence on her spouse.

When traveling to and from Egypt the countess was seldom seen aboard the khedivial yacht al-Mahroussa. In order to keep the rumormongers abbey she would use regular passenger liners between Alexandria and Trieste or Constantinople. Most of the time the travel dates coincided with Abbas Hilmi's separate travel arrangements aboard the royal yachts.

In his article published 3 May 1928 in the Nationalzeitung, Abbas Hilmi's former Hungarian classmate and aide-de-camp, Kelemen A'rvay (Clement d'Arvay), describes Djavidan Hanem as "A rare beauty and an intelligent warmhearted lady who had a soothing influence on the often petulant Khedive." Kelemen goes on to describe how the countess had been an early love of the Khedive's youth and later his second wife. "She lived in splendor in Mostorod Palace near Matarieh. The fantastic property came with a large garden and extensive agriculture domains, whose revenue was assigned to her. She was the good spirit for Europeans at the Khedivial court."

In her memoirs entitled "Harem" published in Berlin in 1930, Countess May, who now referred to herself only as Djavidan Hanem, attempts to describe the controversial life of women in the confined splendors of the Sultanic and Khedivial haramliks. She intertwines insights to the Khedivial court with snippets of own romantic relationship. For instance, she describes how she lived between the palaces of Abdin (Cairo) and Ras al-Tin (Alexandria), and how summers were spent at the khedive's villa in Tchibukli, Turkey. "The saray (palace) of Tchibukli is perched on a hill overlooking the Bosphoros just north of Istanbul."

Situated on the Asian side of the straits, Tchibukli Saray and the nearby Tchiftlik Chalet were close to Djavidan Hanem's heart. It was there that she spent intimate holidays with the Khedive away from officialdom.

above: Khedive's villa (designed by Antonio Lasciac and Delfo Seminati) on Asian side of Bosphoros

Khedive's grandson Prince Abbas Hilmi at Tchibukli with visitors

Yali of Walda Pasha Amina Ilhami at Bebek now Egyptian consulate in Istanbul (altered by Antonio Lasciac)

frequently used by Khedive Abbas Hilmi during his travels the royal yacht SS Mahroussa was twice refitted to keep up with times and twice escorted Egyptian rulers into Italian exile: Khedive Ismail in 1879 and his grandson King Farouk in 1952

In Harem, the countess claims she took an active role in the creation of Tchibukli Saray right from its drawing board (architect Antoine Lasciac; assisted by Delfo Seminati) phase to the selection of the wallpaper and upholstery material as well as interior furnishings imported from France and Germany via Messrs Ballin. It was also Countess May who assigned and approved the landscaping of the palace gardens, its winding footpaths, each re-planted tree, every rose bush, not forgetting 'lovers lane' connecting Chalet to Saray which held such a special memory for the royal couple. From the Chalet's vantage location they would watch together as the illuminated ships plied through the narrow straits.

What Countess May fails to mention is that from its high vantage point Tchibukli Saray a.k.a. Hidiv Kasri overlooked several other sarays and yalis belonging to various members of the Egyptian royal family. For instance in the small village of Emirgan, directly opposite Tchibukli on the European side, was the yali of Princess Iffet Hassan (today Sabanci Museum).

Also at Emirgan stood the saray of the late Khedive Ismail (later destroyed by fire). A few kilometers north at Yenikoy, was the handsome yali of Saiid Halim Pasha. He would later become grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire. More importantly, on the European shore of the Bosphoros, almost diagonally south of Tchibukli Saray, stood the wooden Rococo palace of Bebek belonging to Abass Hilmy's mother, Amina Elhami, a granddaughter of Viceroy Abbas I. Many years later the Khediva-mother would deed it to the Egyptian government. Which is why upon her death in 1931, it was duly turned into a legation and then into the Egyptian consulate-general.

Another item Countess Torok omits is the polemic raised in Istanbul regarding the Tchibukli saray tower. First, there was the issue of the flag. Yildiz Saray (seat of the Turkish government), took offense to Khedive Abbas hoisting the khedivial flag. After all this was not an embassy. Secondly, in September 1906, the wags in the local newspapers claimed the tower was a looking point from where the khedive's men planned to set up a telegraph antenna in order to communicate with the British fleet to the detriment of the Ottoman state!

In Egypt, Countess May took part in civic affairs. As a member of the Red Cross she brought solace to victims of the first Balkan War of 1912 (Bulgaria vs. Ottomans). By order of the Khedive, the wounded, mostly from Kavala near Macedonia, were allowed to recuperate in the palace of Ras al-Tin, its halls and long corridors having been transformed into a temporary hospital. The khedivial entourage meanwhile stayed at Montazah Palace, which, according to Countess May, was Abbas Hilmi's favorite residence. He had personally masterminded its development supervising the construction of its Viennese style salamlik, planning its deepwater harbor and the planting of its pine forests. When at Montazah, Abbas Hilmi and Countess May traveled to Ras al-Tin by special train with the Khedive personally in control of the small locomotive.

Djavidan Hanem was fond of Montazah preferring it to her official Cairo residence at Mostorod where the Khedive kept a private zoo. It was to Mostorod that Abbas Hilmi dispatched exotic animals, gifts from foreign rulers such as the Sharif of Mecca's two desert greyhounds to which, Bosso, Countess May's little black dog, did not take to too kindly.

At Mostorod, Countess May entertained wives of foreign dignitaries with performances on her Bechstein grand piano. Sometimes, with the assistance of an Italian lady painter, she occasionally staged seances. It was during one of these exhilarating events when she discovered she was the reincarnation of a Persian sheik dead 100 years earlier. A member of the countess's entourage who disapproved of these occult services reported them to the Khedive. The seances were abruptly stopped.

Because court protocol discouraged royal consorts from participating in state events, Countess May, with the complicity of her amused husband, would sometimes attend disguised official receptions dressed up as a man. It was as a young palace official "dressed up in an irritating stuffy high collar and tarboosh that I accompanied the Khedive on 8 February 1909, at the laying of the final stone during the heightening of the Aswan Dam" recounts Countess May in her memoirs. Attending this event was Queen Victoria's son the Duke of Connaught with whom, as Princess Djavidan Hanem, Countess May toured Luxor.

With time, the countess became a master of disguise. On one of these occasions, forgetting he was supposedly addressing a male courtier, the Khedive looked affectionately at his disguised paramour exclaiming "Mon amour, est ce que tu n'es pas fatigée?". A court minister within earshot was dumbstruck.

Almost a year before he was deposed on 19 December 1914, Abbas Hilmi separated from his Hungarian countess. Rumors circulating both in and outside the court claimed the khedive was seeing Georgette Mesny a.k.a. Andrée de Lusange whom he met at Maxim's in Paris the previous summer. According to Kelemen A'rvay, the couple had returned to Egypt together aboard the 'MS Helwan'. Lusange "was a 20 years old short, lean, heavily painted woman who distributed her favors for 20 francs and once in the khedive's entourage spied for the French government."

A'rvay, who did not hide his antipathy for the khedive's new courtesan describes her as the demon. "It was her intrigues that pushed Djavidan Hanem to leave the palace and return to Europe."

During his exile the Khedive continued his relationship with Lusange traveling with her all over Europe showering her with expensive gifts and jewelry. In his diary, the exiled head of Egypt's Nationalist Party, Mohammed Farid, describes Lusange in the most unflattering terms. "She came from the lowest, least well-reared, least polite class of the nation. Endowed with no striking beauty or seductive figure or even a moderate amount of all these qualities, she was nevertheless "Beneficiary of an expensive ring offered to her by the Khedive in Geneva." Farid laments even further claiming that about this time the Khedive's two student-sons, Princes Abdel Moneim and Abdel Kader were in desperate need for money in their Fribourg College.

It was in Austria that Countess May received her divorce papers dated 7 August 1913. These were signed by the President of the Alexandria Sharia Court, Sheik Hassan al-Banna (not to be confused with the preacher who would make history as the founder of the Moslem Brotherhood). Concurring this document was the Grand Mufti of Egypt Sheik Bakry Ashour al-Sadfi.

The Khedive's marriage to Countess May although consummated with love and passion had been childless. According to documents left behind by the Khedive's private secretaries Padel, Meissner and Havel, the deposed Abbas Hilmi continued to support his ex-wife financially up to the end. This could be the reason why May Countess Torok von Szendro refused to revert to her maiden name and to what had become a meaningless title now that the Austro-Hungarian Empire had disintegrated. Instead, she preferred to be addressed as Djavidan Hanem, ex-wife of the Khedive of Egypt. She remained an Ottoman (subsequently Turkish) subject, true to her adopted faith until her death.

On 18 February 1922, Countess May received from the Imperial Ottoman Consulate in Danzig what must have been one of last Ottoman passports. The Sultanate ceased to exist as of November 1 that year.

Life after divorce although far from easy never wanted for color or excitement. During WW1 Djavidan Hanem opened a salon in Vienna selling cosmetic articles. She made the acquaintance of composer Eugène d'Albert with whom she perfected her piano. Other acquaintances included Czar Ferdinand of Bulgaria, Austrian novelist Robert Musil, Norwegian writer Olav Gulbransson and German author-playwright Gerhart Hauptmann.

Between the two Wars, Djavidan Hanem found it hard not to succumb to the temptations, glamour and decadence of Berlin's golden '20s. The German capital had become Europe's cultural hub, a Mecca for the more daring members of the performing arts. The ex-princess made a dash for the motion pictures and theater planks, her latest vocation earning her occasional cover stories, some of which were picked up by the Egyptian press. But with painful disappointment Countess May realized she was two generations too late and no match for younger rivals like Marlene Dietrich or Lucie Mannheim. It was too late for stardom and Josef von Sternberg would not cast her as Lola in his 1930 production "The Blue Angel".

Re-settled at No. 49 Schlueterstr Berlin-Charlottenburg, Djavidan Hanem gave piano concerts, wrote short plays for the radio and authored several works including "Back to Paradise", "The Great Seven", "Soul And Body" and "Gulzar". During WW2 she took refuge in Vienna and immediately after the Germans surrendered, moved to Innsbruck where she worked as an interpreter for the French Military Government in July 1945.

When the ex-Khedive died in Geneva in December 1944, which coincided with the 30th anniversary of his overthrow, Countess May's Khedivial pension was discontinued. Postwar times were hard and by 1950 the financially broke 73 year old ex-princess was no longer the charming beauty of yesteryear. Desperate for money she succumbed to the machinations of devious press agents on the make.

In Too Rich, a biography on King Farouk, William Stadiem tells how Djavidan Hanem was brought to Paris by an unscrupulous agent extraordinaire, Guido Orlando. "Shame was Orlando's prescription" says Stadiem, as he recounts how the Italian fortune hunter orchestrated a hunger strike by the ex-wife of the Egypt's former Khedive. Djavidan Hanem was to feign a "Collapse of malnutrition" while cameras flashed outside the mansion she allegedly once owned in the 16th arrondissement.

"A former Queen of Egypt starving to death" screamed the following day's headlines. While Orlando milked this riches-to-rags saga for all its worth, the despondent Djavidan Hanem ended up as Emperor Haile Selassi's (of Ethiopia) wardrobe mistress, the ploy to extort financial assistance from Egypt's reigning monarch having failed miserably, according to Stadheim.

Refusing to divorce herself from the enticing spotlights, Djavidan Hanem made it back to the media once more, this time as a supplicant for an entry visa to the United Kingdom. In his Herald Tribune column of 31 March 1951, Art Buchwald relates how, having recuperated from her pathetic hunger strike fiasco, Djavidan Hanem resorted to picketing the British Embassy in Paris. Her motive was a visa enabling her to travel to London to take a screen test for the film Queen For A Day produced by Alfred Golding of Eureka Holdings. The story was about an hotel housekeeper mistakenly cast to play the role of a queen, so why not use someone who had played the role in real life?

Meanwhile, a Parisian newspaper cashing in on the free publicity, claimed Djavidan Hanem owed her beauty and stately demeanor because she "Daily consumed a sugarless yogurt mixed with raw vegetables and riz à l'orientale." The media circus was having its day with Djavidan Hanem.

Her publicity days over, the aging ex-princess settled down in Graz, nicknamed Pensionopolis for its high incidence of retirees. In her twilight years she took to painting and shortly before passing way, exhibited her latest art works entitled "Visions On The Nile".

Djavidan Hanem, born May Countess Torok von Szendro, died a forgotten woman in Graz on 5 August 1968, aged 91. She was buried at the cemetery of St. Leonard with only a few Moslem students from the nearby University in attendance.

To learn more about other First Ladies of Egypt click Consorts.

For House of Mohammed Ali family tree click here.

Djavidan Hanem's tomb in Austria (courtesy of Puskas Istvan).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|