|

egy.com suggests following articles

|

EGY.COM - HISTORICA

TIMRAZ AL AHMADI MOSQUE AND THE TUFENKJIAN-CHAMSIS

edited excerpt from the book "Privileged for Three Centuries; The House of Chamsi Pasha"

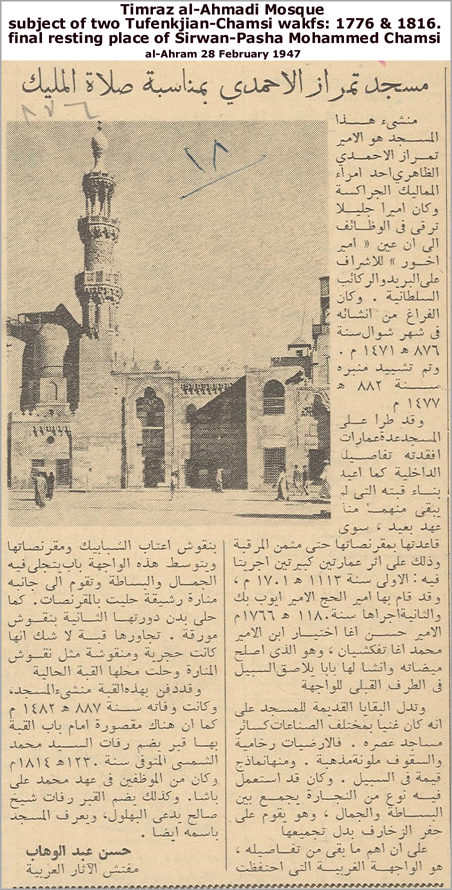

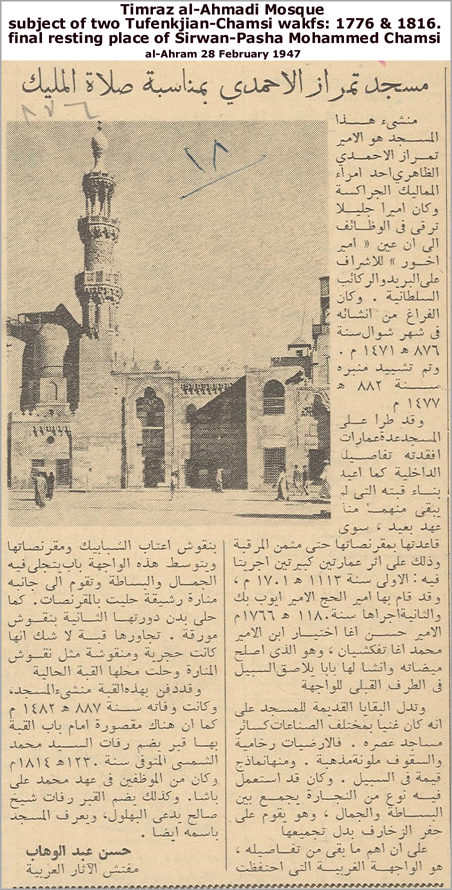

1947 al-Ahram article by Islamic Antiquities Inspector Hassan Abdel Wahab giving a brief history of Timraz Mosque

entry by Ali Mubarak Pasha (1824-93) appears in his late 19th century compilation of al-Khitat al-Tewfikia which provides a detailed, street-by-street description of Egypt's major cities.

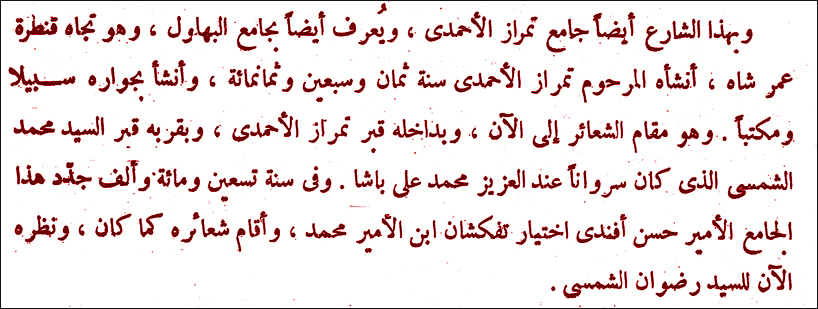

"… also on this street [Port Saiid ex Khalig Street] is the Tamriz [Timraz] al-Ahmadi Mosque a.k.a. Behloul Mosque, facing Omar Shah Bridge. Built in 878 Hejira by the late Timraz al-Ahmadi it includes an adjoining sabil and madrassa. It is currently used for [religious] invocations and recitals. Within the mosque is the tomb of Tamriz al-Ahmadi. Buried next to him is Mohammed al-Chamsi who was Serwan to the cherished Mohammed Ali Pasha. The mosque was restored in 1190 Hejira by Amir Hassan Effendi Ikhtiyar Tufenkjian son of Amir Mohammed, and therein was celebrated his passing. The Mosque is presently administered by al-Sayed Radwan al-Chamsi."

Mubarak is unaware of the blood relationship linking Amir Hassan Tufenkjian to Serwan Mohammed and Radwan Chamsi.

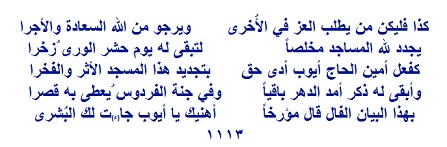

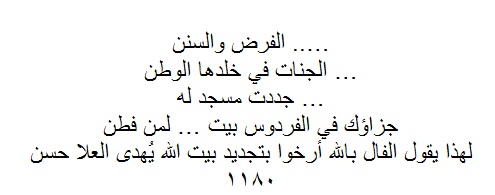

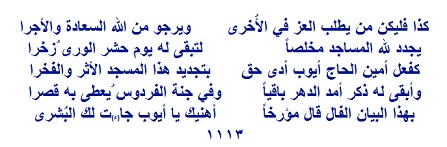

plaque inside mosque dated (1113 H) 1701 the year Ayub Bey renovated the Mosque

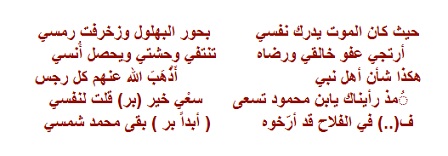

Mohammed Chamsi son of Mahmoud mentioned on cracked marble plaque located above his tomb

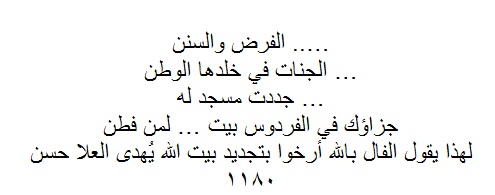

plaque above side entrance dated (1180 H.) 1766 the year Amir Hassan Tufenkjian-Chamsi renovated the mosque and added this entrance facing the Sabil

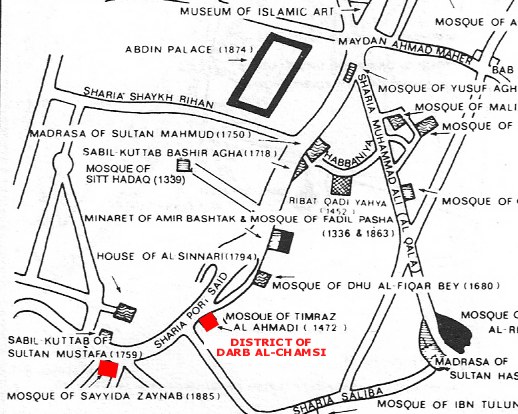

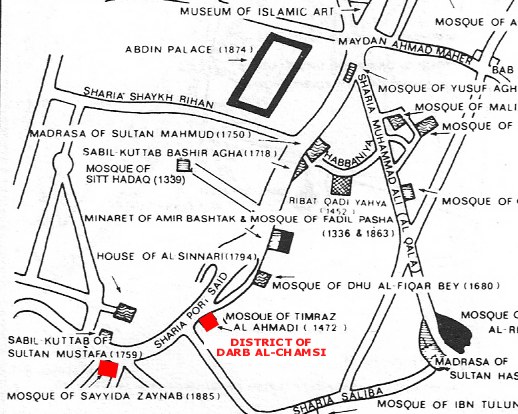

BUILT CIRCA 1471 during the reign of the great Mamluk Sultan al-Ashraf Qa'it Bey, Timraz al-Ahmadi al-Zahiry (also spelt Tamriz) Mosque stands at No. 2 Port Said Street, a few hundred meters north of the Cairo landmark shrine of Sayeda Zeinab. And if truth be told, it was thanks to a leading 18th century Cairene family that the mosque is still with us today, which explains why one of its members, Ser-wan Mohammed Chamsi, is buried therein.

Which brings forth two questions: What exactly was the relationship linking this 18th century family to this specific 15th century mosque? And who were these celebrated pre-Mohammed Ali era Chamsis?

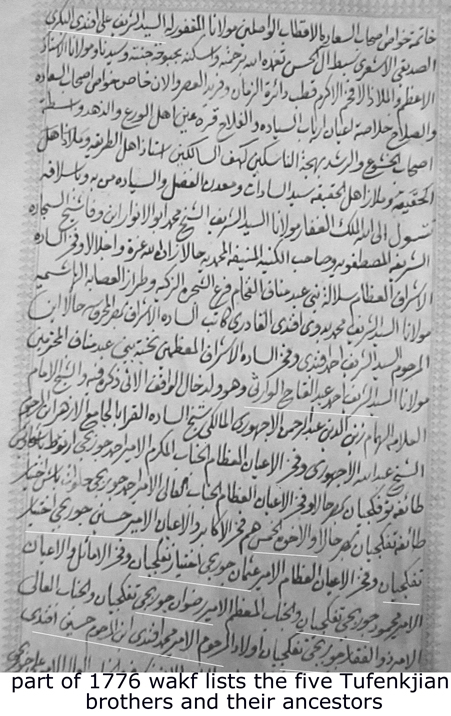

The relationship is best described in two waqfs [also spelt wakfs], or trusts, separately drawn up by different members of the Chamsi family. Aside from introducing us to the contemporary Chamsis, the more recent document also gives us some Cairo geography. For instance, we learn that in the early 19th century, Timraz mosque stood diagonally opposite Qantaret al-Seba'a, or Lions' Bridge, an important Khalig (Canal) crossing. Today, neither the bridge nor the canal exist both having disappeared in 1933 to make way for modern Cairo.

According to the same document we learn that Mohammed Chamsi was no ordinary person. Although not a ser-askar, or army general, he was all the same aide-de-camp to Viceroy Mohammed Ali, which accounts for his military rank of Ser-wan Pasha. [abbreviation for ser (head)- yaweraan -(aide de camp].

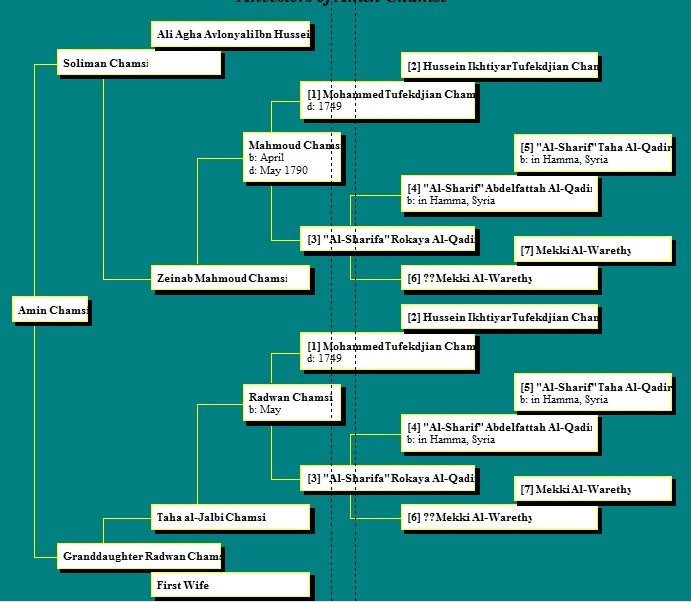

It turns out the said Ser-wan was the last in a long line of ikhtiyariya, or army officers. Over two centuries, his father (Mahmoud), grandfather (Mohammed) and great-grandfather (Hussein) had all served in the Ottoman Mounted Musketeer Corps then known as the Tufenkjian. Deriving its name from the Turkish tufenk (also spelt Tufek), meaning musket or rifle, the Tufenkjian together with the Tcherkess and Gonullyan made up the Ottoman spahi, or cavalry.

Essentially conscripted from the Kurdish satraps of Asia Minor, the Tufenkjian arrived in Egypt circa 1517 when Sultan Selim I crushed the Mamluk armies at the decisive battle of Marj Dabeq. As months became years and years turned into centuries, the Ottoman Army of Occupation was obliged to recruit from within its own ranks; sons succeeding fathers or enlisting descendants of the old Mamluk caste. This two-fold process gave birth to a homegrown version of the Tufenkjians, Yeni-Kareya (Janissaries), Gonulyan etc.

For more than two centuries these army units remained a ruling cast apart, and in order to protect their bloodline they either married from within or alternately wed Jarias (slaves) imported mostly from the Balkans (Bosnia, Hersek, Mora) or Tcherkess from the Caucasus by way of the thriving slave market in Istanbul.

Back once again to our document where we learn that the Ser-wan’s uncle had already restored the mosque a century earlier and that he too had created a wakf to its benefit. This understandably solicits the next two questions, why did the ser-wan's uncle, Amir Hassan Ikhtiyar Tufenkjian-Chamsi have the title of Amir, and why did he restore Timraz mosque in 1766?

In the Mamluk context an Amir, or Knight, had under his command and at his personal expense anywhere from five to five hundred mounted Mamluks. Although we ignore how many men were under Hassan Chamsi's command, we know he acquired added prestige by restoring a sacred site. Not only did the crumbling Timraz mosque stand at the western corner of the historical district of Darb al-Chamsi, or Chamsi borough, but it also bordered the ancestral Chamsi townhouse.

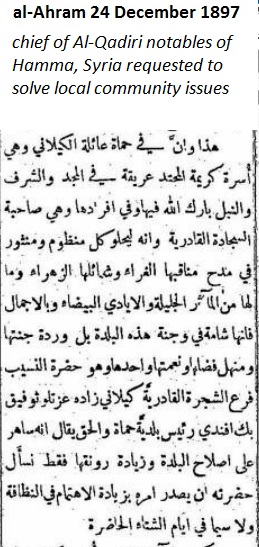

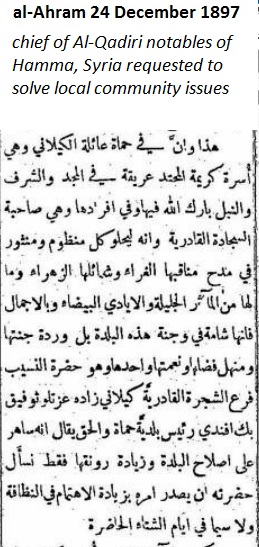

Over and above the "Amir" title we discover Hassan Chamsi was also a "Sharif" as well as a leading member of the mystic Qadiri Sufi Order. This is the order which had been created back in the 12th century by the patron saint of the Kurds, Sheik Abdel Qader al-Kilani (or Jilani). A sub-division of the much larger Sufi family, the Qadiris were first among equals at the latter days of the Ottoman Court in Istanbul, and it was probably during Hassan Hassan Chamsi's lifetime that Timraz mosque became one of Cairo's principal Qadiri zawyas, or shrine.

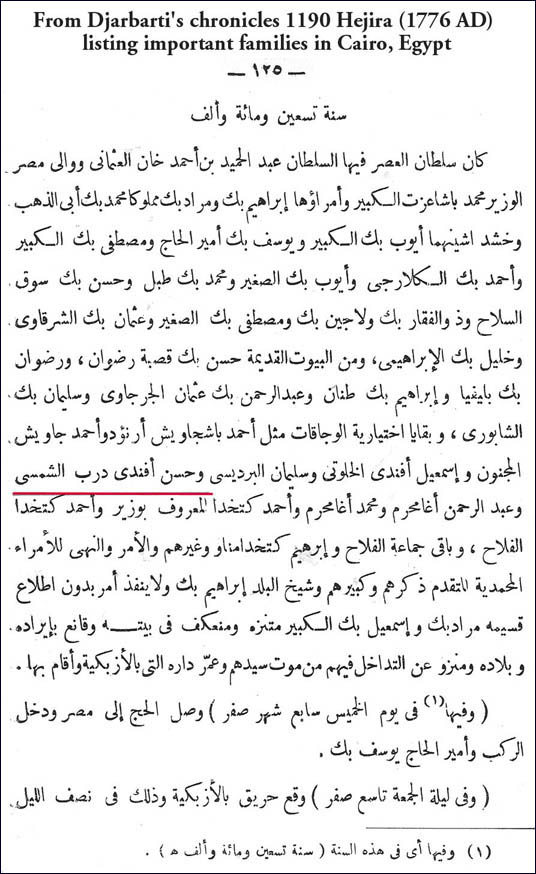

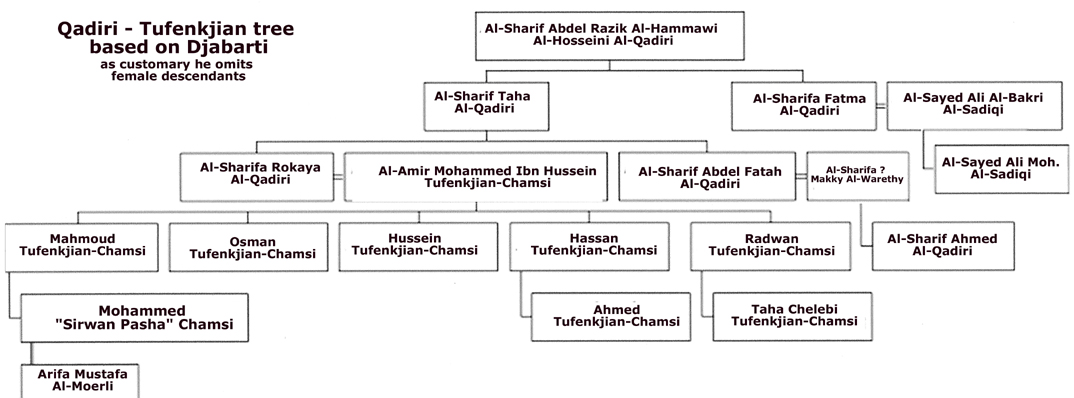

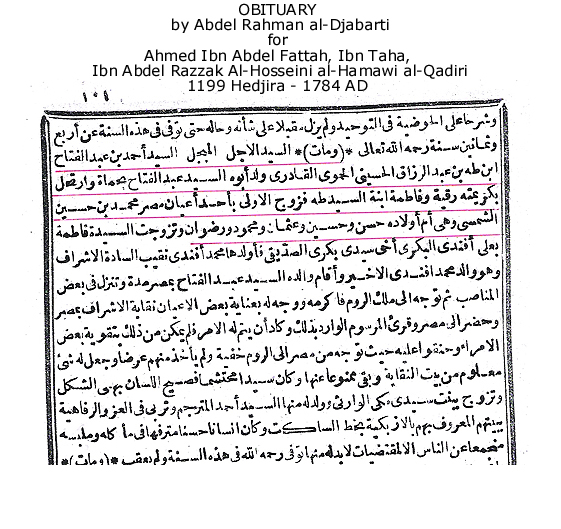

In order to acquaint ourselves with the relationship between Timraz mosque, the Qadiri Order and the Chamsi amirs, we turn to Abdel Rahman al-Djabarti's landmark Cairo Chronicles where the eighteenth century historian supplies us with a number of titillating insights.

To begin with, Djabarti describes the Tufenkjian-Chamsis as one of several ambitious families seeking a power-sharing role in 1754. Fourteen years later, on 2 September 1768, during Ali Bey al-Kabir's tyrannical reign, Amir Hassan Chamsi and his four brothers are exiled to the Hedjaz on charges of defiance. Six years would pass before they were allowed to return, presumably pardoned by Egypt's new Ottoman wali, or governor.

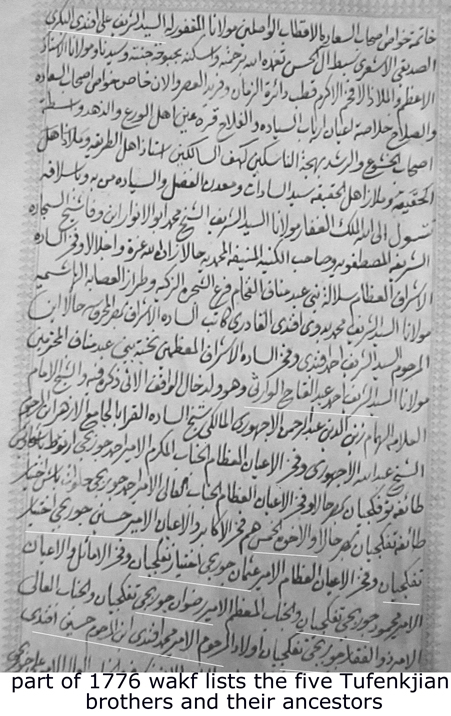

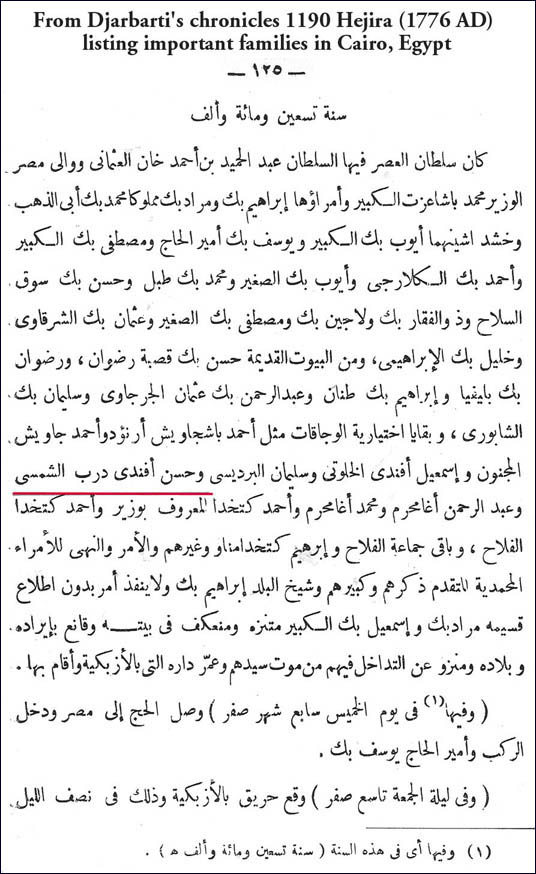

No sooner had the Tufenkjian-Chamsi brothers settled down when once again they are at the forefront of events, this time during a 1776 power struggle that almost led to civil war. On that occasion, Djabarti splits the vying clans into three categories: The notables, the ikhtiyariya and the odjaks, or regiments. He then sub-lists the Chamsis as members of al-bayout al-kadeemah, or old nobility, as opposed to the newcomers featured at the top of his list.

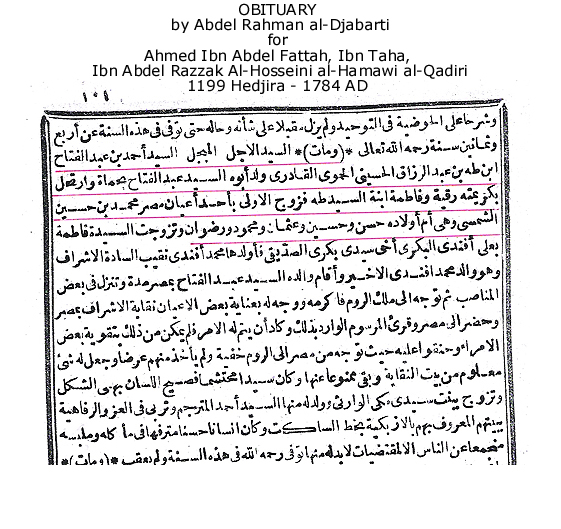

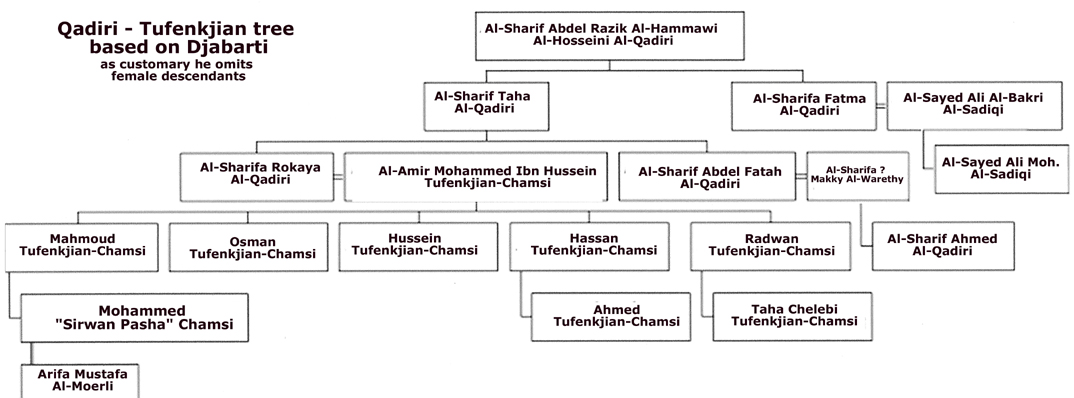

Djabarti's first mention of the Qadiri-Chamsi relationship takes place in 1784, on the occasion of the death of a Chamsi brother-in-law, al-Sharif Ahmed Ibn Abdel Fattah Ibn Taha Ibn Abdel Razzak al-Husseini al-Qadiri al-Kilani al-Hammawi; a stretched-out name belying descent from Prophet Mohammed via Abdel Qader al Kilani. It also implies the departed originated from the town of Hamma in Syria where the Qadiri-Kilanis were [and still are] its exemplary chief notables, just as they were in other cities across Syria and Irak.

As was his habit, Al-Djabarti peppers his eulogy with tidbits surrounding the departed's family. In this case he recounts how Ahmed's "Handsome father," al-Sharif Abdel Fattah, hailed to Egypt from Hamma in Syria settling in the then high-born district of Ezbekieh; that Ahmed's mother was the daughter of nobleman al-Sharif Makki al-Ware'i. Djabarti also mentions that Abdel Fattah found appropriate suitors, one for his sister al-Sharifa Fatma Bint Taha, and the other for his own daughter al-Sharifa Ruqaya.

"While Fatma married Ali Efendi al-Bakri, the brother of the head of Egypt's notables, Ruqaya married a leading squire, Amir Mohammed Tufenkjian Chamsi."

Also, according to Djabarti, al-Sharif Abdel Fattah was summoned to Istanbul-Constantinople in order to receive a Sultanic firman, or diktat, naming him naqeeb al-ashraaf of Egypt,

"But in view of hostile local opposition was never able to exercise his new function."

By naqeeb al-ashraaf, or chief of nobles, al-Djabarti is referring to the venerated post of leader of the Prophet’s progeny in Egypt. Up until the Mohammed Ali era, the post of naqeeb was regarded as a critical position in the overall state hierarchy. The said noble and his extended family were entitled to special privileges as well as the title of either al-Sharif or al-Sayed.

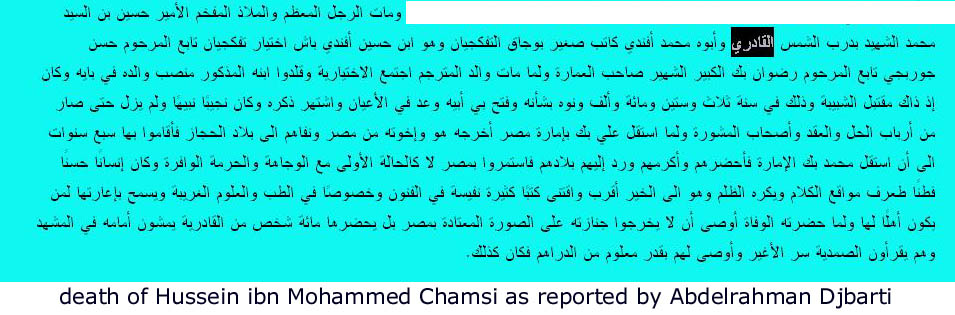

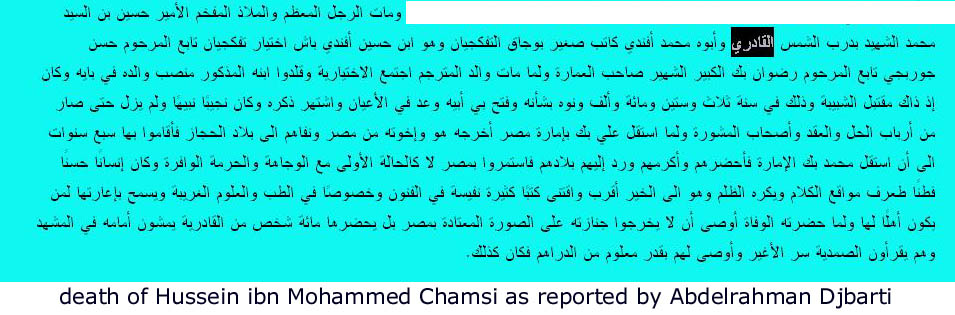

In another section of his chronicles, Djabarti relates that Ruqaya and Mohammed Tufenkjian-Chamsi had five sons, later known as the Hejazi exiles. Djabarti sets aside an extensive eulogy for three of them: Mahmoud in 1790, Osman in 1791, and Hussein in 1795. In the latter eulogy, Djabarti again mentions the Qadiris. After listing Amir Hussein's literary talents and numerous vocations, along with the usual flatteries and honorifics, we are informed he requested 100 Qadiris to walk in his funeral procession performing a Semadia, or ritual dance, accompanied by folk lutes and sung poetry, after which they were to be compensated with dirhams. The funeral procession was to depart from Timraz mosque, the then-Qadiriah shrine of reference.

"Est mort aussi le respectable emir Hussein fils de Mohammed, connu sous le nom de Darb el Chamsi el kaderi. Son pere, Mohammed Effendi, qui etait un écrivain attaché au corps de Toufoukdjiah, etait fils de Hussein Effendi, chef des anciens de ce corps, suivant de Hassan Charbadji, suivant de Radouan bey el Kebir, célebre par les constructions nombreuses et magnifiques qu'il fit élever.

Apres le décés de son pere, l'emir Hussein fut nommé par les anciens de l'Odjak aux fonctions laissées vacantes par celui-ci. C'etait en l'an 1163 [1749 AD], et il était alors dans sa pleine jeunesse. Il acquit une grande notoriété et il devint un des puissant du jour. Aly bey, s'etant rendu indépendent, l'éxila avec ses frères au Hedjaz. Ils y'resterent pendant sept années jusqu'a l'avenement de Mohammed bey Abou Zahab. Celui-ci les rappela au Caire et il leur rendit tous leurs biens et toutes leurs concessions.

L'émir Hussein etait un homme auquel l'arbitraire répugnait; il possedait une bibliotheque choisie et il prétait ses livres aux personnes qui pouvaient les estimer. Sentant sa fin approcher, il regla lui-meme son convoy funebre; il voulut que se convoi fut conduit par cent personnes appartenant a la confrérie des Kadriah, qui liraient certaines prieres. Sa volonté fut exécutée."

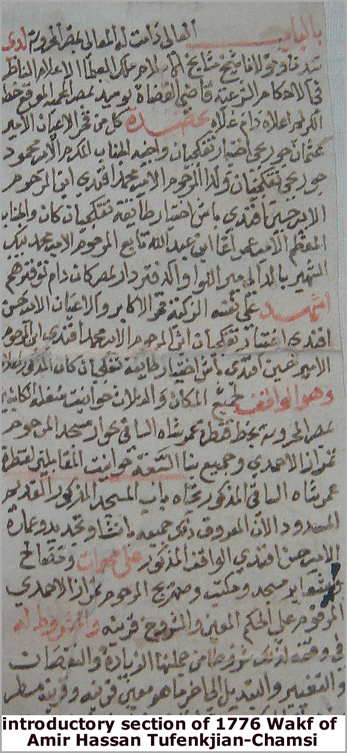

Leaving Djabarti for a while, we return to our documented paper trail which, as already mentioned, consists of two waqfs drawn up consecutively in 1776 and 1816. Both give additional insight into the Chamsis and how, from Mamluk-style amirs, they became devout members of ahl al-bayt or ashraaf.

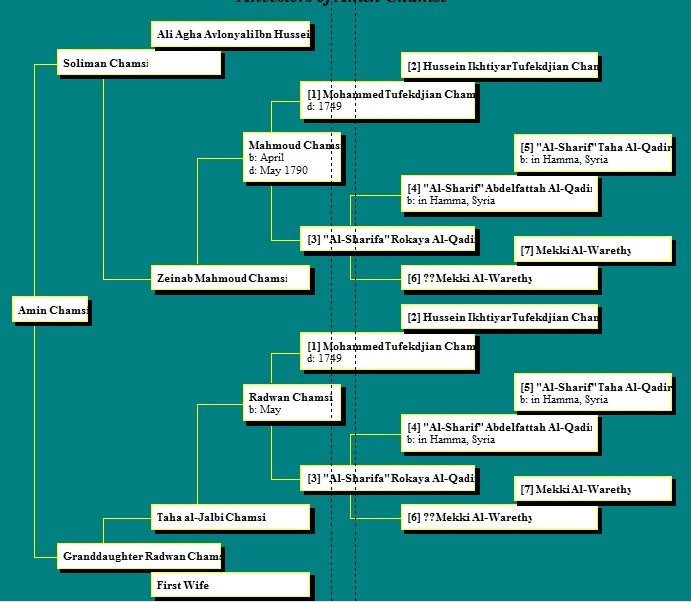

Examining the waqf drawn up on 9 Safar 1231 (10 January 1816) by Ser-wan Pasha Mohammed Chamsi and his wife Arifa Bint Mustafa al-Kashef al-Mora-li Ibn Mahmoud, we quickly deduce Arifa's father came from the province of Mora in what is today Peloponese Greece. Similarly, another part of his name evidences that he occupied the post of Kashef, or minor governor.

Cross-referencing with Djabarti we learn that Mustafa al-Mora-li was indeed the sometime governor of Tora Liman, or Tora Port, south of Cairo. Having previously served under the chief Mamluk Amir, Murad Bey, he was later employed by Mohammed Ali Pasha as a key intermediary between the renegade Mamluks and Egypt's new ruler. Djabarti then recounts that it was al-Mora-li who negotiated the crucial 31 March 1806 Giza ceasefire between Amir Mohammed Alfy Bey and Egypt's viceroy. A repeat performance occurred when, according to Djabarti,

"Mohammed Ali Pasha Again made use of Mustafa al-Mora-li's services on 23 June 1810 but this time the truce discussions were with another set of renegade Mamluk amirs camping outside the Upper Egyptian town Beni Sueif."

But, according to our chatty chronicler, serving Mohammed Ali did not necessarily provide immunity from the ruler's henchmen.

"A few weeks after the notorious Citadel massacre, the pasha's frenzied soldiers wantonly pillaged the sarays and okels of certain Mamluk Amirs including the homes belonging to the vice-regal warden of Shubra park, the esteemed Zulfiqar Katkhoda, as well as Amir Agha al-Wardani, and Mustafa Kashef al-Mora-li."

By liquidating the warring Mamluks during the 28 February 1811 Citadel Massacre, Mohammed Ali did away with the controlling military caste that had ruled Egypt for five centuries. By the same token, he could now embark on his plans to modernize the army starting with the removal of its antiquated regiments including the Tufenkjian and its sister Corps.

For the friends and relations of the massacred victims their primary concern now was protecting their assets from future uncertainties. One way was to draw up ironclad waqfs. This was the path taken by Mustafa al-Mora-li's daughter and son-in-law when they divided up their assets into three separate categories, each with its own codicils. One of these was a waqf khairi, or charitable trust, requesting that the proceeds of 60 feddans of "Black mud-land known as silt" in Mansurah province were to be distributed in perpetuity for charitable purposes. Hence the instructions that on a given night each year, money was to be distributed and the Qur'an read at Timraz Mosque in honor of the Ser-wan's uncle--the same man who had financed the restoration of the mosque in 1766, and who in September of that year, had drawn up his own waqf, the original copy of which lies in the dungeons of the ministry of awqaf.

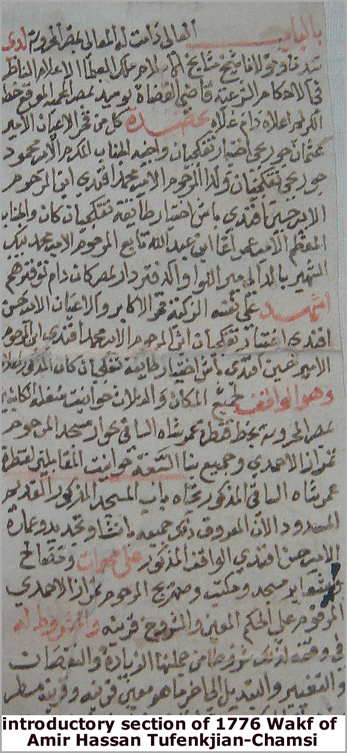

Upon examining the colorful 1766 waqf, one realizes it dealt mainly with the maintenance of the refurbished Timraz mosque, with special reference to its annexes including its sabil, or drinking fountain, and its madrassa, or religious school. At all costs, Amir Hassan Tufenkjian-Chamsi wanted to preserve the Zawya for the next generations of Qadiris and Chamsis, which is perhaps why he summoned Egypt's leading Ulama, or clergy, to witness the said document.

GENEALOGICALLY SPEAKING, we now have two starting points for the Tufenkjian-Chamsis separated by a fifty year interval. The earliest is al-Sharif Abdel Fattah of Hamma, Syria, who, by simple calculation, is situated circa 1650. The second is Ser-wan Mohammed Chamsi's great-grandfather Hussein Efendi Bash-Ikhtiyar Tufenkjian, who could conservatively be placed circa 1680 or earlier.

Without doubt, the last of the military Tufenkjian-Chamsis was Ser-wan Mohammed Chamsi. Whereas his childhood coincided with the waning days of Ottoman-Mamluk rule, his adolescence was marked by Napoleon's decimation of Egypt's territorial armies. To many historians the momentary French invasion served as a dividing line between Egypt's past and future. No doubt Mohammed Chamsi was part of the latter. Propped up by his military heritage, he readily found employment in Mohammed Ali's Nizam al-Jedid, or modern army, becoming captain of the pasha's guards with the title of Ser-wan Pasha.

By now, and with good reason, the family moniker Tufenkjian was discontinued. With an expiring Ottoman Empire giving way to regional nationalism, none of the ensuing Chamsis thought it necessary to revive what would soon be regarded as an archaic military rank. Moreover, Mohammed Ali had re-organized the army so that old-style Ottoman military titles were now depassé.

APART from Ser-wan Mohammed Chamsi's waqf and the negligible write-ups on Timraz mosque, information on the ser-wan remains scrappy to say the least. He does, however, get a fleeting mention in Djabarti's chronicles.

"Ser-wan Pasha Mohammed Chamsi was responsible for organizing the double-wedding procession celebrating the marriage of two of Viceroy Mohammed Ali's children in 1813."

The ser-wan died shortly thereafter signaling the effective passing of the ancestral Chamsis save for a Taha Chamsi Pasha who appears momentarily during the reign of Mohammed Ali's grandson. According to Ilyas Ayub's book 'Egypt Under the Reign of Ismail', Taha Chamsi "was Ismail's nazir of the Khassa Khediwiya," or director of the Privy Purse. Like his earlier relation he too was involved in bridal arrangements, but this time it concerned the two-week wedding extravaganza of Khedive Ismail's three sons: Princes Tewfik, Hassan and Hussein.

Successive nazirs of Ser-wan Mohammed (ibn Mahmoud Tufenkjian-Chamsi) waqf were:

Arifa bint Mustafa al-Morali Ibn Mahmoud (died circa 1836)

(posssibly) Taha Chalbi ibn Radwan Mohammed Tufenkjian-Chamsi; Arifa's second husband following the early demise of his first cousin Ser-wan Mohammed Chamsi

Amin Chamsi Pasha (great-grandson of Mahmoud Tufenkjian-Chamsi)

Mohammed Amin Chamsi Bey (eldest son of Amin Chamsi Pasha)

Abdel Halim Amin Chamsi Bey (youngest son of Amin Chamsi Pasha)

Baheya Ahmed al-Alfy (eldest living granddaughter of Amin Chamsi Pasha)

followed by a state-appointed trustee in 1964.

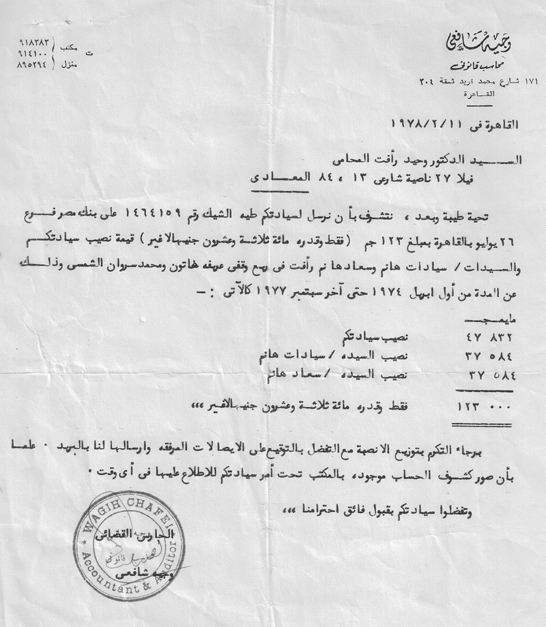

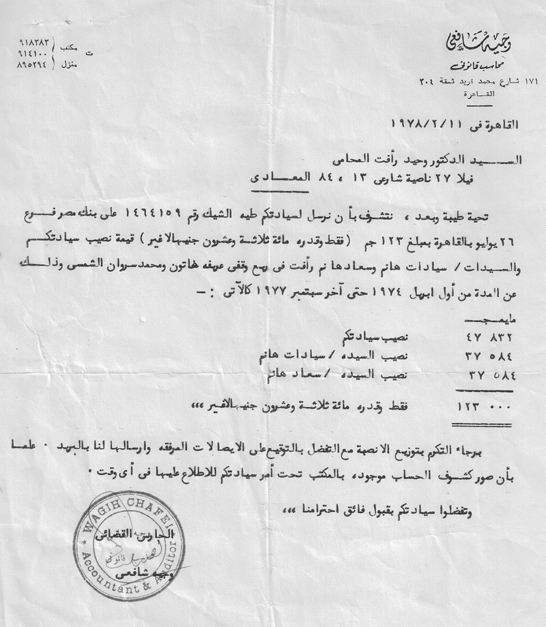

From that date onwards, none of Chamsi's remaining descendants either cared or were aware that a Ser-wan Mohammed Chamsi was buried in Timraz Mosque. And since much of the waqf's related assets had already been expropriated by the state for the expansion of Midan Sayeda Zeinab, none knew the whereabouts of the remaining assets save for a ramshackle coffee shop overlooking Port Saiid Street, a few meters to the south of Timraz Mosque. According to a receipt dated 1978 the waqf then brought in an annual income of just under LE 1000 divided into about 30 different unequal shares representing the number of beneficiaries on that date. The revenue being what it was, understandably no one pursued the matter any further.

Author of subject book is a descendant of Ser-wan Mohammed Tufenkjian-Chamsi and is in possession of copies of the two waqfs...

Email your thoughts to egy.com

© Copyright Samir Raafat

Any commercial use of the data and/or content is prohibited

reproduction of photos from this website strictly forbidden

touts droits reserves