|

egy.com suggests following articles

|

|

Several of my articles on Garden City were plagiarized word for word by novelist MEKKAWI SAID (winner of the Egyptian State price for literature!!!!) and re-published under his own name in a three-part series in El-Masry El-Youm daily in September 2015. Cheers to our "talented" literature prize awardee. Your pain his gain !!!

|

EGY.COM - GARDEN CITY

'BAYT AL LURD'

THE BRITISH EMBASSY

|

by Samir Raafat

Cairo Times, 29 April 1999

|

Just as a coquettish dowager would smack lipstick across her desiccated face, the British Embassy's century-old wrought iron portico recently received an overdue facelift, with blue, red and gold paint applied to the frame straddling "VR", the imperial crown and the lonely thistle.

To those on the diplo-watch, this eleventh hour attempt at rejuvenation signifies a royal visit. As it turns out the Princess Royal a.k.a. Anne Windsor is having tea and biscuits with a few privileged subjects during a Cairo whistle stop.

Perhaps someone should inform the princess that it was on the embassy's riverfront lawn, at the very place where Lord Allenby kept a pet marabou stork, that the very first inkling of her mother's betrothal to Philip of Greece was brought up in conversation between Lord Mountbatten and the young suitor. Himself a great-grandson of Victoria Regina (hence the VR initials on the Embassy gate), India's last viceroy was related to most of Europe's royal families. So why not arrange a marriage between a favorite nephew and a niece?

The present embassy as we know it did not come easy. It took several longs dispatches and supplications before it eventually became a reality in 1894. Here is an excerpt from a letter written in October 1886 by Lord Cromer to his superiors in London. At the time he was living in the center of what we know today as downtown Cairo.

"The house which I at present occupy is in no way adapted for an Agency (embassy). The reception rooms are far too small for the number of people whom I am obliged to entertain. As regards sleeping apartments there is only just enough room for my family which only consists of my wife, two children and a governess. If I have to receive any visitors as was the case when the Viceroy returned from India I am obliged to go to the trouble and expense of sending my children to an hotel." (see bleow for full text)

The reply approving a new embassy building came in 1892.

The new embassy's colonial building was designed by R. H. Boyce and contracted by A. Huntely, a local superintendent of public works). The building and its fine-painted walls and ceilings was an all-in-one residence-chancery. Built in the last decades of the nineteenth century (circa 1892-3) at a cost of LE 39,984, it was referred to as The Agency--al-Wekala just as the old embassy on Adly (ex Magrabi) Street had been. Cramped out by a swelling bureaucracy, Lord Cromer had pushed Whitehall and to purchase the new, bigger property, sandwiched between the riverfront palaces of Kasr Al Aali and Kasr Al Walda Pasha.

The British proconsul couldn't want for a better location. At the turn of the century the surrounding district of Kasr Al Dubara was where the creme de la creme had already taken up residence. Lofty neighbors assured it was now for the British to improve their already ailing new residence. At first there was the water seepage problems which meant the basement floor had to be raised above the Nile flood level. Then it was the turn of providing a constant source of electric power. Hence the purchase of a steam-driven generator entailing a high maintenance cost. Furniture proving to be inadequate meant repeated requests to the foreign office for extra funds some of which were promptly refused.

It was only after the creation of the new suburb of Garden City, causing the demolition of the palace of Kasr Al Aali, that the embassy expanded its gardens southwards having purchased in 1916 for LE 36375 an adjoining piece of land belonging to Mr. Charles Bacos (the man responsible for the creation of the adjoining district of Garden City). Hence the reason why Rustom Pasha street ends where it does today: at Amrika Al Latiniya Street and not at the Nile bank as it originally did—with the purchase of the Bacos property the separating narrow street was speedily incorporated into the embassy grounds.

As the years went by different occupants sought new changes to the embassy not all of them acceptable to the paymaster in London (Lords Harding and Curzon) . For instance Lord Allenby’s request to enlarge the residence building in 1920 was aggressively turned down with the remark that “if Lords Cromer and Kitchener had both lived there (in the residence) than Lord Allenby might do the same.”

Another contemporary addition to the embassy was the adjacent ballroom (today the visa section). As for the crescent-shaped chancery fronting ex-Sharia Al Tombak, this came much later, at about the time when the Walda Pasha Palace made way for several high-rises including the new Shepheard's Hotel.

It was from the embassy veranda and behind its large wooden doors that imperial policy affecting the destinies of Egypt and the Middle East was conducted by empire-builders Allenby, MacMahon and Lloyd. In fact the nickname "Bayt Al Lurd" (the Lord's house) originated as a reference to the building's first occupant, Sir Evelyn Baring (later Lord Cromer), Egypt's virtual ruler for two decades.

Up until the fall of the empire, Cromer's successors ran Egypt's affairs in typical imperial fashion so that in February 1942 it was from the embassy gates that Sir Miles Lampson (later Lord Killearn) headed with a persuasive military cortege towards Abdeen Palace to offer King Farouk two choices: appoint a pro-British cabinet or abdicate. The young monarch complied and kept his throne for a few more years.

But those days of obeisance would soon be over. The shock of losing superpower status was brought home to the British in October 1954 when Sir Ralph Stephenson saw a large chunk of his embassy grounds disappear. As a result, the embassy which for half a century had symbolized power in the Middle East, lost its bomb shelter, its swimming pool, its Nileside dock and 5000 square meters of freshly cut English lawn. In their place a now liberated Cairo would have its corniche.

Contrary to what historians like to say, the land swap was conducted with the best diplomatic comportement. In exchange for the land ceded by the British government, Egypt credited Her Majesty's Treasury the sum of LE 300,000 amounting to approx. LE60.00 per square meter for land originally purchased by the British at three pounds per square meter. It was all very cricket!

But the Empire would strike back one last time.

Cairo's corniche was barely two years old when Britain and France, in an unholy alliance with Israel, occupied the Suez Canal area in October 1956. As a result the Union Jack stopped fluttering above Garden City-Kasr al-Dubara. And by the time it was discreetly re-hoisted a few years later the mystique of Bayt Al Lurd was no more. In the national psyche the British Embassy and its compound had been reduced to the status of 'just another monument'.

Except for faint echoes of earlier grandeur brought on by occasional royal visits, the historic residence is now used mostly to promote trade deals and cultural exchanges. Instead of state dinner parties where guests in white ties and medals trooped into the ballroom according to strict protocol, there are now charity bazaars and garden carousing where Lord Kitchener's stork had once reigned supreme.

Those who occupied Bayt al-Lurd until the writing of this article:

1883-1907 Sir Evelyn Baring (Lord Cromer) - British Agent and Consul General (lobbied untiringly for the building of a new embassy)

1907-1911 Sir Eldon Gorst - (British Agent and Consul General)

1911-1914 Lord Kitchener - British Agent and Consul General (his pet stork protected him from women)

1914-1917 Sir Henry Macmahon - High Commissioner

1917-1919 Sir Reginald Wingate - High Commissioner

1919-1925 Field Marshall (Lord Allenby) - High Commissioner

1925-1929 Lord Lloyd - High Commissioner

1929-1933 Sir Percy Loraine - High Commissioner

1933-1936 Sir Miles Wedderburn Lampson (Lord Killearn) - High Commissioner (with Italian wife Jacqueline Castellani)

1936-1946 Sir Miles Wedderburn Lampson (Lord Killearn) - Ambassador (ceded his bedroom to Winston Churchill)

1946-1950 Sir Ronald Campbell - Ambassador

1950-1955 Sir Ralph Stevenson - Ambassador (oversaw the reduction of his embassy grounds)

1955-1956 Sir Humphrey Trevelyan - Ambassador (first British diplomat to be evicted from his embassy)

diplomatic relations broken over Suez crisis; Monsieur Charles Albert Dubois of Switzerland moves in

1959-1961 Sir Colin Crowe - Chargé d’Affaires

1961-1964 Sir Harold Beeley - Ambassador (Lady "Pat" Beeley livens embassy to unprecedented levels)

1964-1965 Sir George Middleton - Ambassador

diplomatic relations broken over Rhodesia crisis

1967-1969 Sir Harold Beeley - Ambassador

1969-1972 Sir Richard Beaumont - Ambassador

1972-1975 Sir Philip Adams - Ambassador

1975-1979 Sir Willie Morris - Ambassador

1979-1985 Sir Michael Weir - Ambassador

1985-1987 Sir Alan Urwick - Ambassador (with Latin American wife; temporarily moves out of embassy in view of massive restoration works )

1987-1992 Sir James Adams - Ambassador

1992-1995 Mr Christopher Long - Ambassador

1995-1999 Sir David Blatherwick - Ambassador (where art thou Lady Beeley !!!)

F A C T O I D S

|

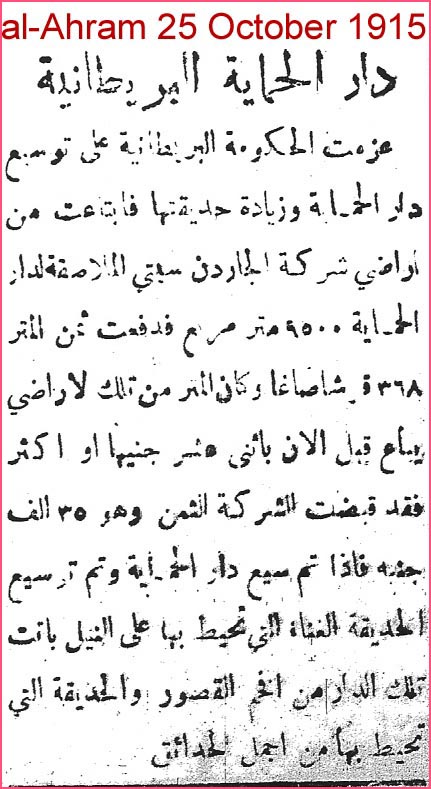

EGYPTIAN GOVERNMENT REPOSESSES PART OF BRITISH EMBASSY GROUNDS

photo of British Embassy reaching Nilebank

There was neither a land grab nor a diplomatic row over the extension of the Corniche on part of the British Embassy property. As is customary in such bilateral issues, civilized nations seek a sensible solution. And so it was when negotiations were concluded between HBM government and the Egyptian ministry of foreign affairs. Talks regarding the vital approach road had been on-going even before King Farouk was toppled in 1952.

In 1954, the newly installed republican ministry of municipal & rural affairs re-launched an ambitious building program which included the extension of the new corniche from Helwan to Boulak. This important milestone entailed widening extended portions of the existing Helwan-Cairo roadway and the construction of an entirely new causeway between Maadi and al-Madabegh Station near what is today Dar al-Salaam. Agricultural farmland, private homes and part of the old Kasr al-Aini hospital, including the house of its director in Fom al-Khalig, had to be removed. Likewise for several alcazars including historic landmark palace of Soliman Pasha in the ancient district of Old Cairo.

In order to link up with the rest of the corniche which sped northwards from Kasr al-Nil bridge through what used to be the British Kasr al-Nil barracks and onwards to the Delta barrage, it was necessary to purchase that part of the Nile frontage that belonged to the British embassy.

Having explored different alternatives, Cairo's municipality and the responsible persons in Whitehall agreed on fair and square compensation. A survey team from the British ministry of public works arrived in Cairo to appraise the situation. They were quick to realize that extending the corniche meant the reduction of the massive British embassy garden by 4,500 to 5,000 square meters. It also meant the elimination of the embassy swimming pool and the loss of a WW2 bomb shelter. And there was also the matter of constructing a new iron and stone base fence.

Taking into consideration that the British government had paid three pounds per square meter in the 1890s, the suggested compensatory amount was pegged at LE 300,000 (in today's purchasing power that would be the equivalent of at least LE 100 million). Without further ado, the Egyptian government agreed with the provision that it settle the amount in three equal installments.

Work would commence in mid-August at which time the incumbent British ambassador Sir Ralph Stevenson and the rest of his staff were in the embassy's summer headquarters at Rouchdi Pasha, Alexandria. (The practice of relocating the entire Egyptian government and foreign diplomatic corps to Alexandria during the summer months was still in effect in the early 1950s.) When Sir Stevenson unexpectedly returned to Cairo on urgent business, Cairo's municipal councilor readily agreed to postpone work on that section of the corniche by several days, evidencing the cordiality of Anglo-Egyptian relations.

WHAT BECAME OF THE "Old Agency" ON MAGHRABY STREET?

As mentioned in above article, Cromer moved to the "New Agency" in Kasr el Dubara around 1893 whereupon the building he previously leased from a Mr. Baird on Maghraby (now, Adly) Street became on 1 December 1893 the headquarters of the Turf Club then run by Harry Aspinall who died in 1929 and was replaced by B. P. Greenwood.

In December 1934 the Turf Club moved further west on the same street on a piece of land purchased with newly raised funds. The services of engineers E. C. Newman and C. R. Bawden were retained for the erection of the new building. This is the same building that was torched during the riots of January 1952.

|

above: original British consulate in Cairo leased from Mr. Baird and deemed 'inadequate' by Sir Evelyn Baring

Below: text from Evelyn Baring (future Lord Cromer) handwritten letter to the Foreign Sercretary in London

urging construction of new residence and chancery

|

|

Cairo, 26 October 1886

Cairo, 26 October 1886

The Earl of Iddesleigh

My Lord,

The question of constructing a house for the British Agency at Cairo has already been before your Lordships predecessors. Last winter Mr. Boyce was sent out by the Board of Works to report on the subject. He estimated that STLG 27000 would be required to purchase the necessary land and to build a house. The proposal was rejected by the treasury on the ground of the expense (see Lord Rosebery's dispatch No. 567 of March 25th 1886)

Before leaving office Lord Rosebery again presses strongly on the Treasury the necessity of building an Agency at Cairo. The Treasury however, adhered to their original decision (see Lord Rosebery's dispatch No. 161 of July 30th 1886)

If I venture to raise the question again it is because I am more than ever convinced that, sooner or later, a house will have to be built, and that delay will increase both the difficulty of finding a suitable site and possible also the expense. The ground selected by Mr. Boyce could have been obtained for 27 1/2 fes a metre. It has since Mr. Boyce visit been sold for 30 fes a metre.

The house which I at present occupy is in no way adapted for an Agency (embassy). The reception rooms are far too small for the number of people whom I am obliged to entertain. As regards sleeping apartments there is only just enough room for my family which only consists of my wife, two children and a governess. If I have to receive any visitors as was the case when the Viceroy returned from India I am obliged to go to the trouble and expense of sending my children to an hotel.

Nothing can be worse that the arrangements of the Chancery. Two very small rooms, one of which was intended to service as a pantry and another which is so hot as to be almost uninhabitable in summer are all I can give for my staff, which consists of 6 persons. This accommodation is quite inadequate. The archives have to be stowed away in different parts of the house which causes very great inconvenience. There is not a single room in the house foe a European man servant, and the rooms for the native servants are very bad and unhealthy.

Yet this is the best house I can obtain in Cairo and I pay STLG 600 a year for it.

I venture to submit to Your Lordship that in view of the position occupied for some time to come by H.M. representative in Egypt it is most desirable that a better house should be provided for the Agency than that which I have described above.

I observe in the letter from the Treasury of July 21st the following passage occurs "It is of course 'necessary that H.M. Representative in Egypt and elsewhere should be properly housed y the experience of each year only confirms My Lords in the view that this end can be attained at far less expenses by means of suitable allowances than by provision in kind."

On this point I beg to submit the following observations. I receive at present allowances to the amount of STLG 1000 a year. There are charges on these allowances amounting to about STLG 600 a year leaving about STLG 400 a year available for the payment of rent. The rent of my present house is STLG 600 a year, being STLG 200 more than the amount covered by the allowances. Is such an arrangement were possible, I should much prefer the plan of drawing allowances and making my own arrangements for a house. But I can most positively assure Your Lordship that even if the Treasury were willing to increase the allowances, no suitable house is to be found in Cairo. I can fully bear out the remarks made by Mr. Boyce in his mem of Feb. 16 1886 upon the houses which he visited in Cairo. He says: "I found them all ill-constructed with bad foundations, the walls cracked, and the damp rising in them." I know of no house in the European quarter at Cairo to which this description does not apply. Further I may add that I do not know of a single house with the exception of that in which I at present live, whose sanitary condition is such that I would willingly run the risk of placing my family in it. I make no exception in favour of my present house in this respect. I have recently, at great expense, had the drains placed in good order.

If therefore anything is to be done, I submit that there is no alternative but to build a house.

In the letter of the Treasury dated March 19th 1886 it is remarked, in commenting on Mr. Boyces' estimate of STLG 27000,that experience had shown that the actual expenditure would very much exceed the estimate. I am aware that in cases of this sort, estimates are very often exceeded but I do not think I am taking too sanguine view in stating that this case will prove an exception to the rule. When Mr. Boyce was framing his estimate I pressed two points on him strongly. The 1st was to build the house solidly, in the first instance as to render it impossible that there would be any frequent demands for important repairs. The 2nd was to make a very liberal estimate so as not to be obliged to ask the Treasury for any supplementary grant. To be quite on the safe side, however, I add STLG 3000 to Mr. Boyces estimates. I feel quite confident that STLG 30000 is the maximum of any expenditure which would be incurred.

I have one further observation to make. I observe that in the Treasury letter of March 9 1886, it is stated that if Mr. Boyces' estimate of STLGF 27000 were accepted, - "the minimum annual statement in the salary and office allowances of the Agent & Consul general required to recoup the outlay 'would be STL 1325 per year. As I have already mentioned the office allowances only amount to STLG 1000 a year, of which, only STLG 400 a year is available for house rent. The proposal of the Treasury would therefore involve the total abolition of all allowances, the deduction of STLG 325 a year from my salary, and I presume the obligation to pay out of my own pocket the charges, mostly on behalf of the consulate, not on my behalf of the Agency, which are no borne by the allowances.

I need hardly say that, if the Treasury maintain this view, all idea of building an Agency must be dropped. I doubt whether there is any diplomatic post in which such heavy expenses are incurred by H.M. Representative at Cairo. The cost of living was always expensive and has greatly increased since the British occupation. The charges which I have to bear on account of entertaining and charities are very heavy. If it were necessary I could give abundant proofs in detail of the accuracy of this statement. My present salary, exclusive of allowances is STLG 5000 a year, and I can assure Y.L. that considerable as that salary is, it would be impossible for me to maintain my present position properly, were I not possessed of a considerable private income. With every wish, however, to make use of my private income in a liberal spirit, I really must decline to bear so heavy an additional charge as would be thrown upon me by the proposal of the Treasury. When I accepted my present post, I understood that the Office allowance covered the house rent. This is, as I have already stated, is not the case. Without, however, wishing to dwell on this point, I submit that the allowances cannot in fairness be reduced by more tat STLG 600 a year, which is the rent I now pay. I am aware that, allowing interest on capital expended this will amount in practise to throwing an additional charge on the Treasury, but I venture to hope that, under all circumstances of the case, H.M. Government will think themselves justified in incurring this charge.

I am ...

E. Baring

|

Email your thoughts to egy.com

© Copyright Samir Raafat

Any commercial use of the data and/or content is prohibited

reproduction of photos from this website strictly forbidden

touts droits reserves