|

egy.com suggests following articles

|

EGY.COM - COMMUNITY

OUR PERSIANS

by Samir Raafat

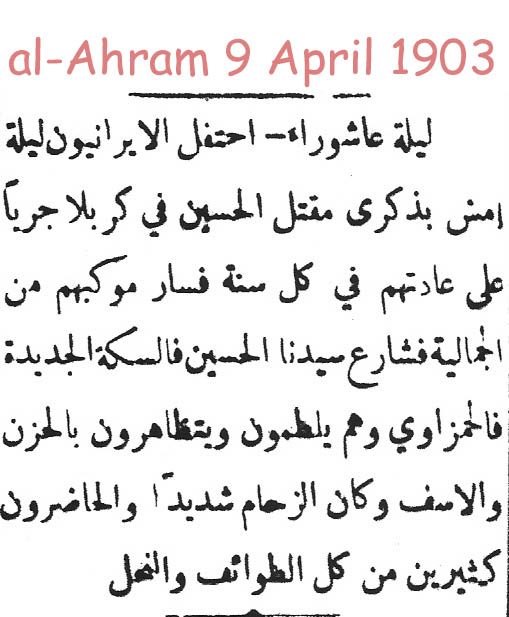

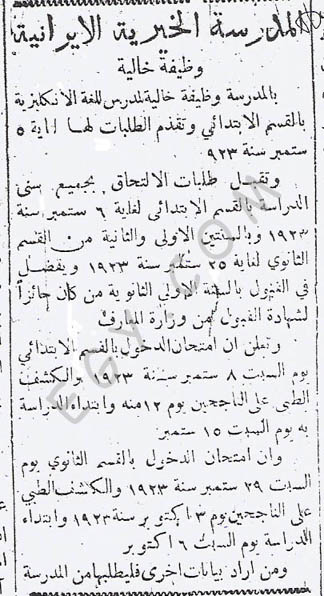

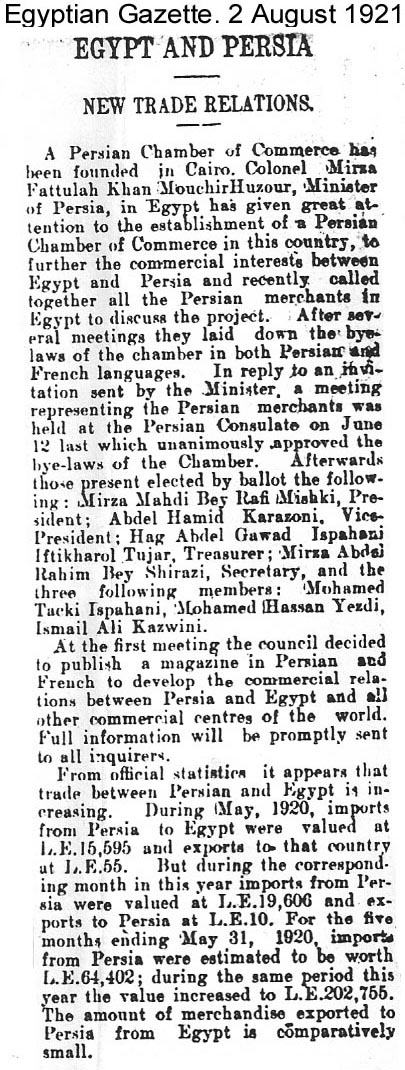

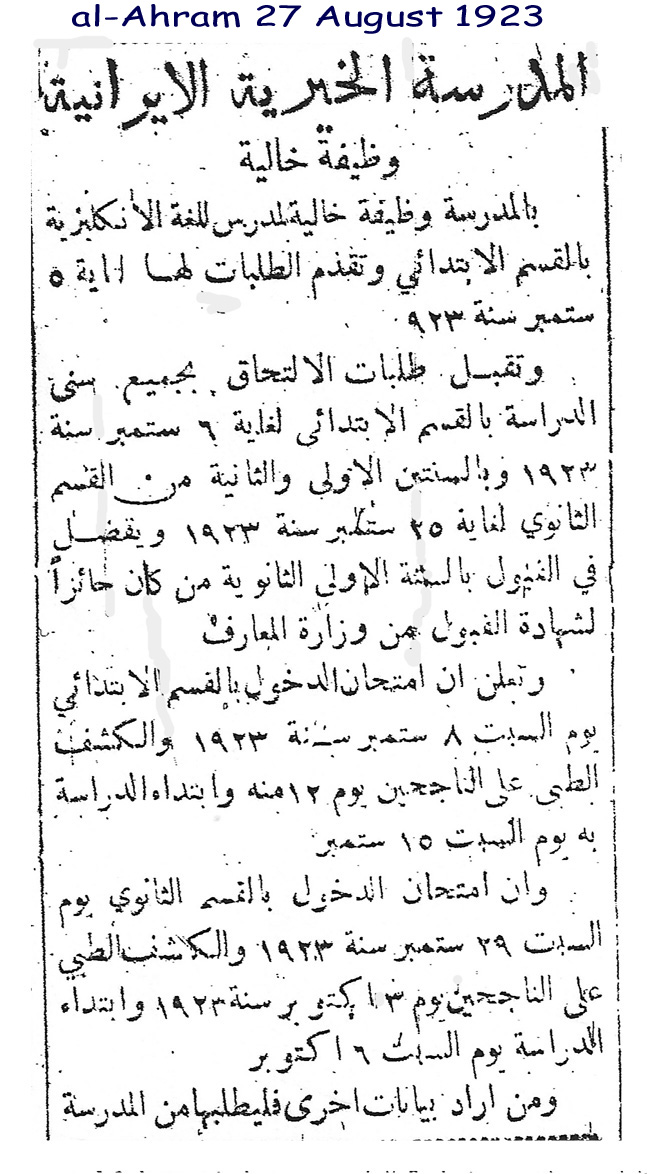

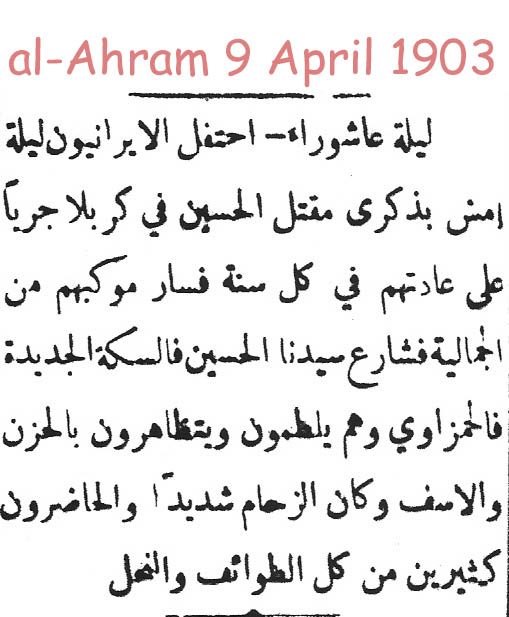

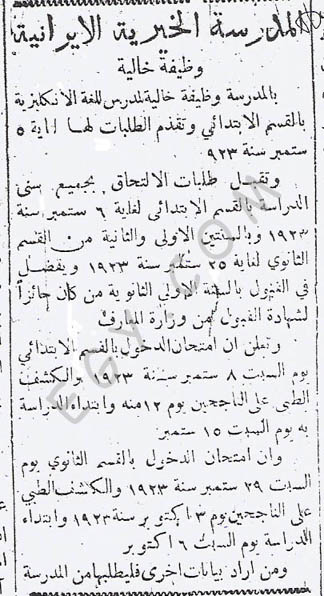

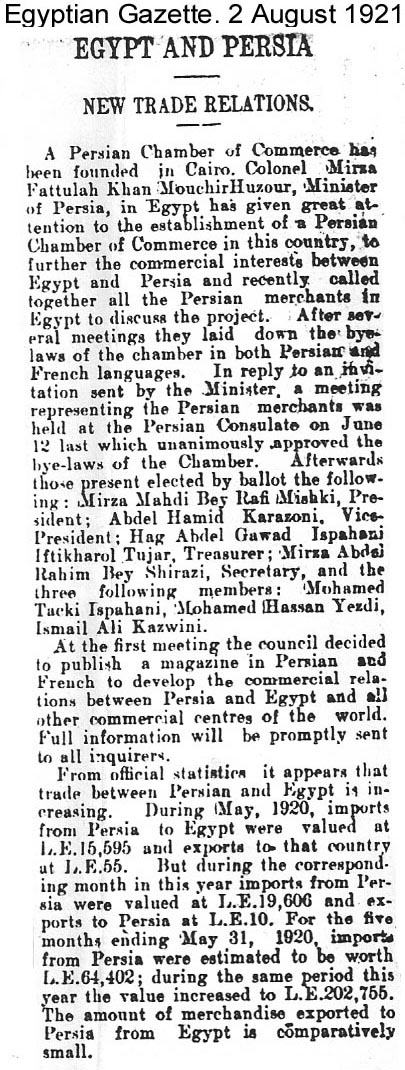

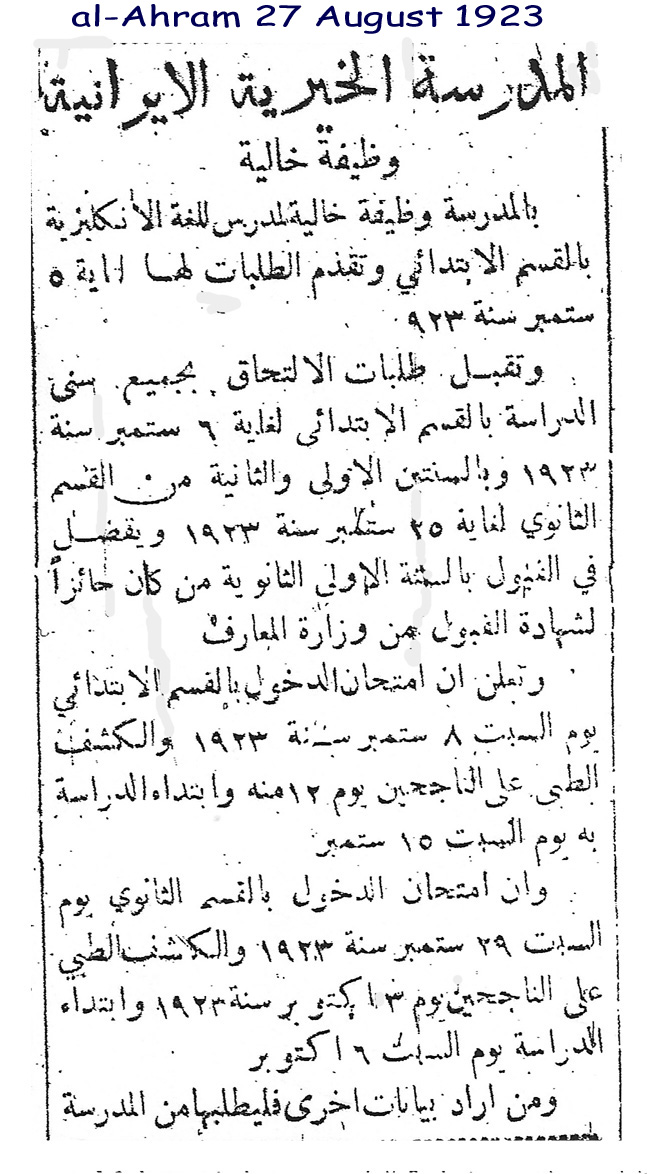

above: celebrating Ahsoura in 1903; advertising vacant position for English teacher at Iranian School al-Ahram August 1923

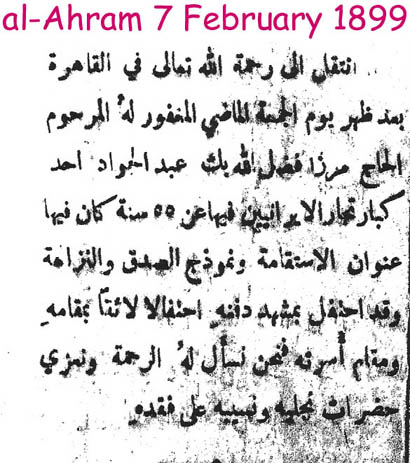

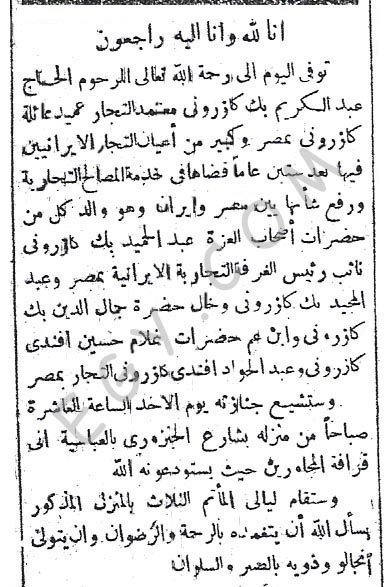

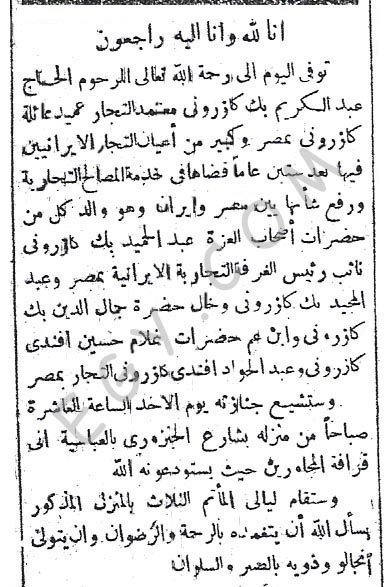

obituary al-Ahram 12 June 1922

advertising handmade Persian carpet

During the 19th century Persian families arriving from Iran, India or Istanbul settled mostly in the Cairo districts of Hamzawi, Mouski, Souk al-Samak al-Kadim and Ghouria. Besides the proximity to Al-Hussein Mosque they took pleasure in living and working next to the other iconic legacies of the Shi'a Fatimid Caliphate, al-Azhar University being but one of them. One should also mention our Persians who were not necessarily Shi'a. These included Persians who were Baha'i, Zoroastrians, Jews and those of Armenian ancestry. But for the sake of this story let's discuss the predominantly Shi'a Persians who made Egypt their home and eventually assimilated into the local woodwork.

During the 19th century Persian families arriving from Iran, India or Istanbul settled mostly in the Cairo districts of Hamzawi, Mouski, Souk al-Samak al-Kadim and Ghouria. Besides the proximity to Al-Hussein Mosque they took pleasure in living and working next to the other iconic legacies of the Shi'a Fatimid Caliphate, al-Azhar University being but one of them. One should also mention our Persians who were not necessarily Shi'a. These included Persians who were Baha'i, Zoroastrians, Jews and those of Armenian ancestry. But for the sake of this story let's discuss the predominantly Shi'a Persians who made Egypt their home and eventually assimilated into the local woodwork.

From among those families we find the Abouela Asfahanis, Abdelrassoul Shirazis, Agamis, Amir-Aghas, Askar Tabrizis, Bakir Qazwinis, Bayat Shirazis, Djidaoui Abdelkarims, Hassan Yazdis, Ismail Alis, Kazem-Boghdadis, Kazrounis, Khozans, Mirza Abdelgawaads, Mustafa Iranis, Namazis, Rafie Mishkis, Shukrallah Kazems, Tehranis, Zadehs, etc.

Almost all were merchants dealing in indigo, silver, tobacco, pigments and tea imports from Iran, southern India and Turkey. Later, some of these traders switched to carpets and rugs from Iran and Central Asia offsetting Turkish imports that had heretofore prevailed in Egypt.

A good example is Haj Mohammed Hassan Kazrouni. Young and ambitious, he forfeited a livelihood in Madras, India where his family owned a trading depot, preferring to start his own trading business in Cairo. This was during the reign of Viceroy Mohammed Ali when Egypt was opening up to the rest of the world and commercial prospects were booming.

Within a few years Kazrouni made his first fortune importing indigo from the Indian sub-continent luring other members of his family to join him. Owning a large house on Midan al-Daher (today a government commercial school) accommodating newcomers was of no consequence for the prosperous Shahbandar al-Tujar or merchant provost.

Another example is Mirza Rafei Mishki who arrived in the 1860s. A merchant par excellence he was prepared to invest outside his realm of competence. No sooner had he settled in Cairo when, in May 1894, he created with leading local tradesmen Hassan Madkour Bey and Osman Fahmi Pasha, the National Company. Their plan was yo invest in large scale agriculture, hence their petition to the then-prime minister Nubar Pasha for a concession of 4,000 feddans near the village of al-Romaan in Fayoum.

But not all Persians in Egypt were members of the influential Traders Guild. The few exceptions were either political exiles, protégés of the monarch or adept chroniclers like Mirza Mu'adab Asfahani who edited a community paper in the early 1900s under the name Chehr-name.

It was during the early years of King Fouad's reign (1917-36) that our Persian traders formed their own chamber of commerce with the post of sir-tujar--provost revolving among the leading families. Yet, according to one of the community elders, the Chamber was ineffective throughout most of its existence. And as though to confirm this negative opinion the Chamber is hardly mentioned in commercial journals, neither is it listed in telephone directories.

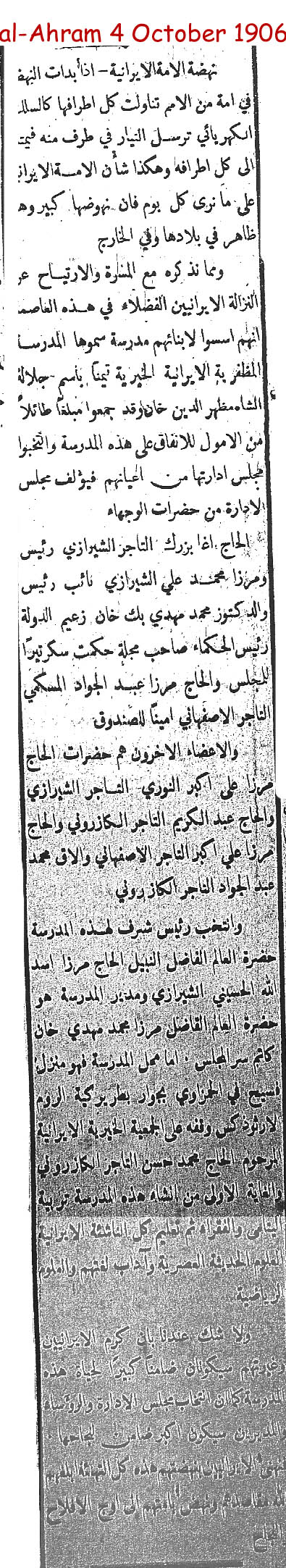

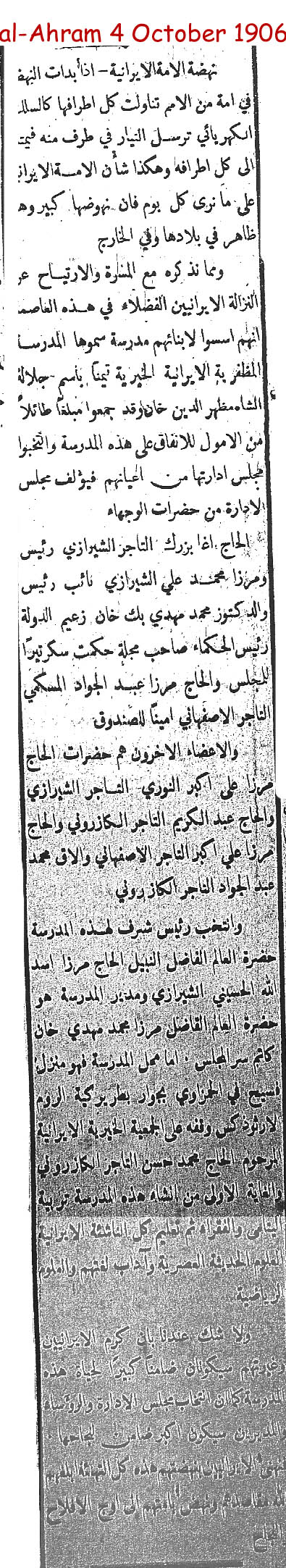

Also in line with other foreign resident communities (Armenians, Austro-Hungarians, Jews, Greeks, French and Italians) the Iranians agreed to set up their own communal institutions. This included an Iranian Community School, which must have expanded to some extent in 1927 necessitating a logistical move from its unpretentious premises in Gamaleya to Saray Ali Salaam located at No. 12 Bahaeldine Ibn Hanna Street, Sikket al-Daher. The school catered to both elementary and secondary levels.

There was also an Iranian Benevolent Society favoring the poorest members of the community. Several of the wealthier members of the community created waqfs--trusts from which proceeds were disbursed annually to Iranian charities.

During his 26 November 1923 speech on the occasion of the departure of the long-time representative of Persia in Egypt, Mirza Mohammed Rafie Mishki Bey tabled in detail his community's many accomplishments. In Egypt since 1864 and operating under four rulers--Khedives Ismail and Tewfik; Sultan Hussein Kamel and now King Fouad, Mishki was eyewitness to many changes in its political and economic scene.

Alluding to their privileged position in Egypt Mishki recalled to mind the excellent rapport between the two great Moslem monarchies with a special mention for King Fouad. The head of the Utaki Tijarati or Irani Chamber of Commerce, went on to applaud the Association of the Orient Jamiayat al-Rabta al-Sharkia, a non-political cultural organization headquartered at 28 Sami Street, in the district of al-Dawaween (the ministries). Throughout its existence it had promoted cultural and literary events for its members who hailed from different areas within Central Asia, India, Persia and the Fertile Crescent. Most active were the association's Iranian members led on by Mishki Bey himself. He continued to perceive it as a forum for partnership and mutual cooperation with the host country.

The calls for rapprochement between Iran and Egypt notwithstanding, as a foreign community residing in what was first a semi-autonomous region within the Ottoman Empire, and later a British Protectorate, Persians in Egypt answered to their own Majlis Hasbi and consular courts regarding civil and criminal matters. Later, under the 1901 decree which replaced the Capitulations system, Iranians in Egypt benefited from the Mixed Court system, an incentive they were keen to preserve at all costs.

For instance, during the 1919 protest riots that broke out across Egypt, Cairo’s Iranian merchant families quickly distanced themselves from the nationalists and their fight for independence. Their concern was primarily to seek indemnification for the ransacking of their warehouses and the looting of their goods. Which is probably why their acting provost wrote to al-Ahram reminding its readers that "Iranians in Egypt were protected under the 1875 Convention ratified between the Ottoman and Persian empires." Hence, the letter implied, they were 'privileged' citizens in an Egypt currently ruled by the British. The letter was signed by Mirza Abdelrehim Shirazi, the incumbent sir-tujar of the Persian traders in Cairo.

Three years later, in January 1922, the nationalist Wafd Party was about to become an important powerbroker in Egypt. Very quickly the Iranian community began to reverse its tune. In a letter to al-Ahram, Ahmed al-Husseini, on behalf of the Persian community, declared he fully shared the plight of his Nile Valley brethren in their struggle against colonial discrimination. "As easterners we support Egypt's quest for self-determination and we join our voice to that of exiled leader Saad Zaghloul."

Due to inbuilt fears of being mistaken for locals in view of their shared physical resemblance and common religion, Iranians living in Egypt continually raised the prickly issue of 'privileges' often mobilizing the Iranian Embassy for intervention. Hence the state of distress within the Iranian community when it was rumored the incumbent Persian envoy Ali Akbar Khan had been recalled to Tehran. Almost immediately the community reposted with a written appeal to the Persian prime minister to rethink his decision.

In an attempt to settle what was for a long time regarded as a grey area on the treatment of Iranians in Egypt, the government issued a related statement on 19 October 1924, followed by a reminder on 8 June 1925, outlining the extent of their privileges. It was now more than evident that the community’s desired capitulatory status was on the wane. After all, the original regime of Capitulations had been created in the 17th century for Christian traders operating inside the Moslem Empire. The Moslem Persians had merely piggy-backed on it.

Capitulations would remain a troublesome issue for the next decade. Meanwhile, in April 1928, in an attempt to do away with this travesty, the Wafd government conveyed its desire to the European powers that it wanted to put an end to this outdated Convention. Foreigners in Egypt, irrespective of nationality, should answer only to Egyptian jurisprudence.

Perhaps because of common faith and other shared values, the first country approached on the subject of revoking Capitulations was Iran. "Do Iranians trust the Egyptian judiciary system?" was the question put forward by an adept reporter to Ghaffar Khan Galal, Persia's representative in Egypt during an April 1928 interview.

The answer was clear-cut. "Iranians in Egypt felt at home. They trusted and respected the host government's sagacity. Arabic had become their first language on par with Persian."

In due course the Persian Empire revoked the Capitulations umbrella, calling upon its subjects living in Egypt to adhere to local legislations in all matters. In fact, a related convention and a Treaty of Friendship were ratified in Tehran on 28 November 1928.

While some countries reluctantly followed suit, the European powers stalled and deferred to the limits of unreason.

Capitulations and the Mixed Court system finally ended in 1946 following years of exhaustive negotiations.

Moslems by birth, the majority of Persians resident in Egypt were of the Shi'a sect. At their tikias--assembly halls located off Azhar Street (one in Gamaliya the other in Hamzawi), they celebrated Ashoura and other traditional holidays in conformity with their rites. Interesting to note that rather than switch to the mainstream Sunni school, some Iranians converted instead to Baha'ism. This was true of certain community elders such as Mirza Hassan Khorassani, Mirza Ali Mohammed Shirazi and (Agha) Ali Reza Asfahani. (Introduced by the Mogul emperors of India the title "Mirza" referred to a learned man).

Despite slight variances in worship and idolization within the small Persian community, when the time came for unity of purpose its members rose to the occasion. For instance, when Iran was hit by one of its chronic but devastating earthquakes in the summer of 1923, Egypt's Iranians quickly mobilized setting up an Earthquake Fund under the joint auspices of the Iranian Chamber of Commerce and the Irani Benevolent Society.

Up until air travel became popular the preferred traveling route between Cairo and Tehran was overland, just like it had been in pre-biblical times, except that now trains and cars had replaced camels. The first overland stop was Haifa in Palestine. Then onwards to Beirut or Damascus. The last stop was Baghdad before taking a 30-hour bus ride into Tehran. An alternate route was through Izmir, Turkey, then onwards by rail to the seaport of Baku (in what is now Azerbaijan), and from there across the Caspian Sea to Northern Iran.

In the 1930s travel by airplane from Cairo to Tehran via Baghdad would take 15 hours.

Mirza Mishki Bey seated next to Cairo governor Shazli Pasha at a freemason gala in July 1938

Partings of leading members of the Persian community were often reported in the press as indeed was the case in May 1924, when Irani Chamber of Commerce chief, Mirza Mahdi Rafei Mishki Bey, headed to Tehran and places beyond. There to see him off at Cairo's Central Railway Station was the head of the Grand Master Loge implying that Mishki Bey was a leading freemason--a fashionable trend for upwardly mobile beys and pashas.

As though by correlation, shortly after Egypt became an independent monarchy, the influx of Persian immigrants decreased considerably. But most likely it had more to do with the changes taking place in Iran which had been in an endless state of decline.

In the mid-20s the old Kajar dynasty was replaced by a dynamic military-monarchy with plans for badly needed infrastructure and a fresh regime of law and order. As a result, economic and commercial opportunities were finally brightening up and city bazaars across Persia were coming out of lasting recession. Moreover, a heretofore unknown petrochemical industrial sector was about to debut on a titanic scale. It now seemed the only ones leaving Iran were government officials and students on educational missions.

As the call of Iran grew stronger some of the younger Iranians living in Egypt, along with some newcomers, decided to return home. Those who remained belonged to the earlier waves of Persian settlers/immigrants who were entering their third and fourth generation in Egypt. They had already begun an effortless process of integration within an overwhelming Sunni-Moslem society.

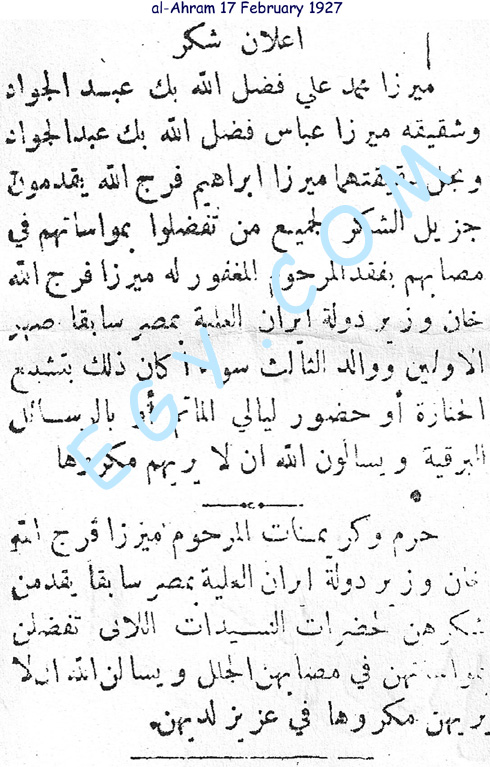

al-Ahram 15 February 1927

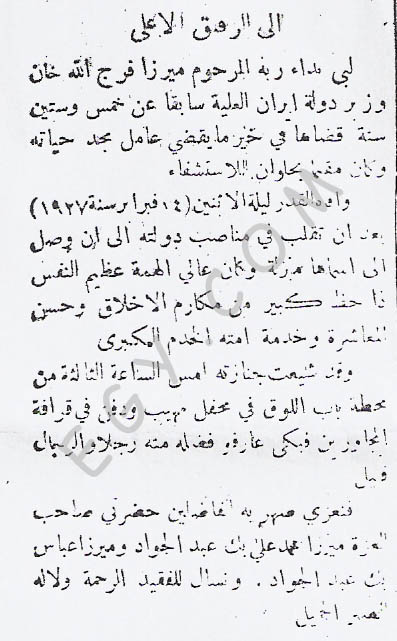

former ambassador of Persia to Egypt Mirza Faragallah Khan died yesterday in Helwan

He was buried at al-Mujaweroon mausoleum of his in-laws the Mirza Abdelgawaad Family

below: member of the Abdelgawaad family

With the passing of the first two generations community members increasingly exchanged their ghetto-like existence of haret al-Ajam for a more open lifestyle, sending their children to the finest schools running the risk some would eventually chose white collar professions over family business and, as a result, become thoroughly "Egyptianized."

A good example is the Mirza Abdelgawaad family, which dominated the top tier of the community's social totem pole leading a palatial existence in Shubra and Alexandria. Thoroughly gentrified, the last of the male line was Cairo's leading interior decorator of the 1960s Fadlallah "Fazlo" Mirza Abdelgawaad. With a keen eye for the beautiful and grand, at his deathbed he asked to be buried with his maternal ancestors whose patriarch was Egypt's several times prime-minister, Mustafa Riaz Pasha (c.1835-1911).

As for the surviving matri-lineage descendants of Mirza Abdelgawaad, they are either major players in the country's economic sector or directors of major multinationals operating in Egypt, as is the case with the current president of the American Chamber of Commerce. The only Irani descendant to have made it to cabinet level was Mohammed-Ali Namazi Pasha. He held the portfolios of transport and justice in 1950-52.

Emulating the Mirza Abdelgawaads, several other second generation Iranian merchants also took up residence in the then-bourgeois districts of Helwan, Abbassia, Helmia al-Gedida and Koubbeh Gardens; later Zamalek and Giza. Some went even further investing in real estate. The Mishkis, for instance, commissioned leading contractor Hettena to construct them an apartment building on Amir Farouk Square.

And breaking with tradition, whereby arranged marriages had heretofore been limited to intra-family or intra- community levels, some of the upper-crust families began marrying into the local Egyptian bourgeoisie. It was time for change.

Keeping up appearances, merchants like Ismail Ali Bey (The Iranian Co.) and Kazarouni Carpets, opened elegant galleries in the modern district of Ismailia, the first opting for the then-fashionable Passage Continental at the hotel by the same name overlooking Opera Square. The latter opted for the elegant Immeuble Baehler on Kasr al-Nil Street. Selling a high-end product they now catered to Cairo's elegant salons. This was a clear indication that our Farsi carpet merchants had successfully created a niche within Egypt's emerging bourgeoisie. Conversely, they could reduce their somewhat precarious reliance on intermittent bulk sales to mosques and religious endowments.

With time, Persia and Shi'ism became a folksy memory diluted with each coming generation. Nevertheless, in the 'resident foreign population' section of the Annual Statistics Journal for 1936-36 we still find an entry under "Iranians".

Yet, unexpectedly, a brief but very exciting reminder of their Persian ancestry announced itself in March 1939 with the engagement and subsequent marriage of King Farouk's sister to the Shahpur a.k.a. the crown prince of Iran.

1937: Shahpur Reza Pahlevi with Sheikh al-Maraghi rector of al-Azhar University

founded in 972 AD by the Shi'a Fatimids Al-Azhar became a learning center for Sunni Muslims around the world

commemorative stamp for the March 1939 wedding of HRH Princess Fawzia of Egypt to the Crown Prince of Persia HIH Shahpur Reza Pahlevi

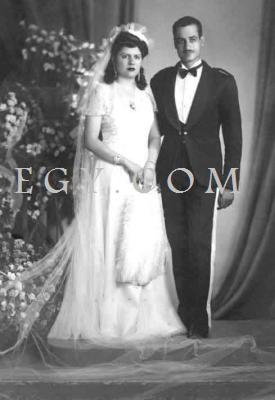

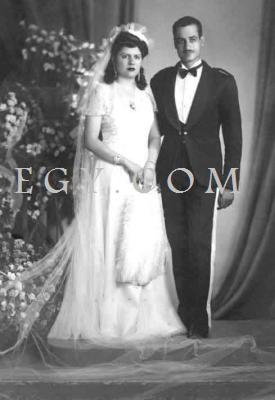

below: Iranian future first lady of Egypt Tahia Kazem-Boghdadi weds officer Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1944

During 30 days of nationwide festivities the Egypto-Persian community went the whole nine yards proudly advertising itself, contributing hefty donations towards a princely gift to the visiting heir of the Peacock Throne. For a while at least life was breathed back into an otherwise indolent Egyptian-Iran Union headed by Prince Soliman Daoud, but actually run by two leading Iranian merchants, Mirza Mahdi Rafei Mishki and his brother Mohsen. What a pleasure it must have been for the Mishkis and their community brethren to celebrate Persian New Year (NowRuz) at Zaafaran Palace on 22 March 1939, in the presence of no less than Shahpur Mohammed Reza Pahlevi.

The dynastic marriage fell through shortly after WW2 and the fairy tale Egyptian-born princess was no longer shahbanu--Empress of all Persians. The tables were slowly turning.

Meanwhile in Egypt, the system of Mixed Courts which had so far privileged foreign communities was no more. As a result, some of the mutamasereen felt they no longer had a future and were making plans to relocate elsewhere. The large Orthodox-Greek and Catholic-Italian communities were reluctantly considering immigrating to 'motherlands' they had never seen before.

The Jews, a few of them Iranian, saw the writing on the wall and were making appropriate contingency plans. And the Melchite and Maronite Shawaam were now calling themselves Lebanese and commuting back and forth between Cairo and Beirut.

By now, Egypt had produced its own homegrown merchants and traders. These competed with, and gradually displaced, both the khawaga and the ajam from whom they had learned so much. But for the Moslem Irani community there was no anxiety, for it had all but melted away, especially now that no newcomers arrived to replenish their dwindling numbers.

Assimilation into, and bonding with, the local social fabric was both inevitable and overwhelming. So much so that when, in 1954, Tahia Kazem-Boghdadi, a daughter of an Iranian merchant, became Egypt's First Lady as Mrs. Gamal Abdel Nasser, no one took note of her origins. Nationalism had overpowered communitarian-ism.

Bringing home the extent of assimilation was a comment made recently by Ali, the blue-eyed grandson of Ismail Ali Bey (d. 1935) who currently owns a large gallery at Khan al-Khalili's Sikket Badistan, that famous alley which swarmed with Iranian merchants and shopkeepers in the late 19th century.

"It was only when I turned 40 that I learned I was of Persian extraction and that my grandfather was brought to Egypt at the age of three. The carpet market has since changed 180 degrees and instead of high-end Tabriz, Keshan, Qashqai and Nain, we now sell Egyptian handmade carpets and rugs, which are beautiful by the way!"

Today, the descendants of Egypt's once bustling carpet, tea and indigo merchants are unrecognizable save for a handful of elderly gentleman who astonishingly resurface when Farah Diba, Iran's former Empress, makes her annual July pilgrimage to the late shah's mausoleum at Cairo's al-Rifa'i Mosque.

If, in 525 BC, a great Persian army vanished without trace in Egypt's Western Desert during the reign of Emperor Cambyse II, not at all surprising therefore that a tiny 20th century Farsi community also disappeared, but this time in a devouring urban jungle.

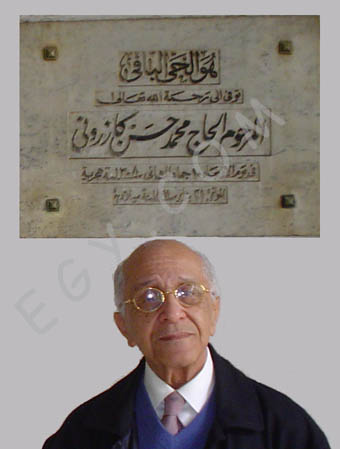

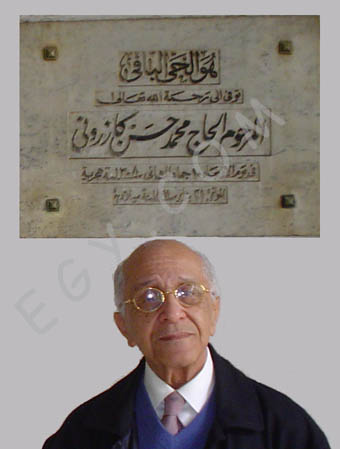

the last of the mohicans... Ali Gamaleldine Kazrouni beneath his great-grandfather's plaque at the beautiful Kazrouni cemetery in al-Ghafir

Farah Diba visiting tomb of Shah Reza Pahlevi at Cairo's al-Rifa'i Mosque; 2006

Email your thoughts to egy.com

© Copyright Samir Raafat

Any commercial use of the data and/or content is prohibited

reproduction of photos from this website strictly forbidden

touts droits reserves

During the 19th century Persian families arriving from Iran, India or Istanbul settled mostly in the Cairo districts of Hamzawi, Mouski, Souk al-Samak al-Kadim and Ghouria. Besides the proximity to Al-Hussein Mosque they took pleasure in living and working next to the other iconic legacies of the Shi'a Fatimid Caliphate, al-Azhar University being but one of them. One should also mention our Persians who were not necessarily Shi'a. These included Persians who were Baha'i, Zoroastrians, Jews and those of Armenian ancestry. But for the sake of this story let's discuss the predominantly Shi'a Persians who made Egypt their home and eventually assimilated into the local woodwork.

During the 19th century Persian families arriving from Iran, India or Istanbul settled mostly in the Cairo districts of Hamzawi, Mouski, Souk al-Samak al-Kadim and Ghouria. Besides the proximity to Al-Hussein Mosque they took pleasure in living and working next to the other iconic legacies of the Shi'a Fatimid Caliphate, al-Azhar University being but one of them. One should also mention our Persians who were not necessarily Shi'a. These included Persians who were Baha'i, Zoroastrians, Jews and those of Armenian ancestry. But for the sake of this story let's discuss the predominantly Shi'a Persians who made Egypt their home and eventually assimilated into the local woodwork.