Ignace Tiegerman

|

|

|

|

|

|

EGY.COM - JUDAICA

|

|

IGNACE

TIEGERMAN

Could he have dethroned Horowitz?

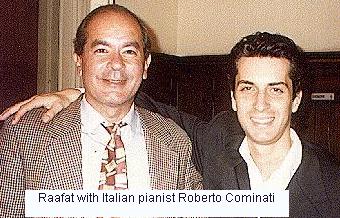

Samir Raafat

Egyptian Mail, September 20, 1997

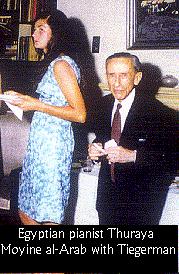

BEING next to Ignace Tiegerman was an experience none of his students could forget. It started with fear and ended with great admiration. "One did not understand what music was all about until he met 'Monsieur'. After a few lessons, if you were lucky to be accepted as his student, you entered a new universe, the universe of music. You started understanding why Chopin wrote the way he did, why Beethoven put a pause after this note, what is legato, and so on, and so on" remembers Stephen Papastephanou, one of Tiegerman's Egypto-Greek students.

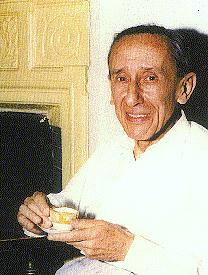

Ignace Tiegerman

There was no discussion with Tiegerman. He was always right. He demonstrated to you how the piece you were preparing should sound, and if you dared argue, all he had to do is show you the score and the notations by the composer, and that was that. Monsieur's demonstrations were beyond belief. When he played the piece for you, it sounded so beautiful, that you almost became convinced that you could not play it. With some coaching however, you started gradually making a decent sound, and you hoped that maybe you could play the piano after all. Tiegerman was full of encouragement, but no praise

In the 3-4 years Stephen Papastephanou studied with him, he heard Tiegerman praising his playing only once. "What was amazing" recalls Papastephanou, "was how he treated you, as if you were a seasoned pianist, with an occasional sarcastic comment such as 'vous n'avez pas besoin de composer, pendant que vous jouez ce morceau'. That, when you played wrong notes."

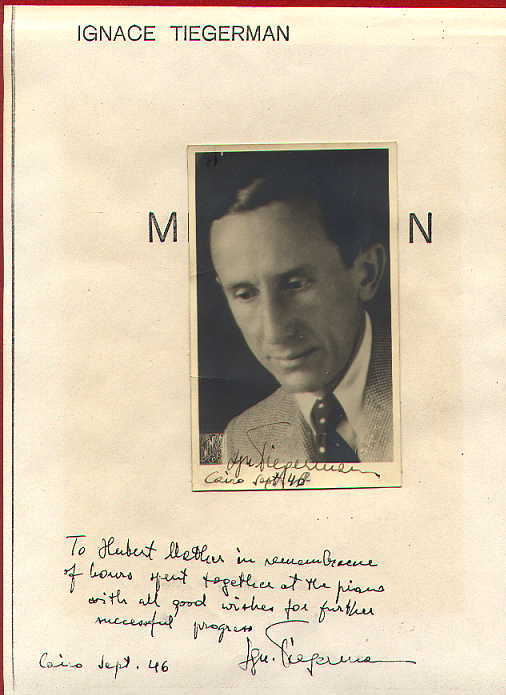

Born in a small town in Poland in February 1893, Ignace Tiegerman spent the second half of his life in Egypt. In his youth he studied in Vienna under Polish pianist-composer Theodor Leszetycki. Other Leszetycki students included suach famous names like Paderewski, Schnabel, Gabrilowitsch and Ignaz Friedman. The latter, while being Leszetycki's assistant, took time to tutor Tiegerman. By his mid teens Tiegerman was pronounced by his masters "equipped to perform in Vienna's Bosendorfersaal" which was tantamount to having made it into the big league.

In 1928, after completing his musical studies in Germany, where he also read philosophy at Berlin University, Tiegerman traveled to the United States with violinist Polokovich. But unlike several East European contemporaries including Vladimir Horowitz whom he knew from his Berlin days, Tiegerman decided against living in America. For health reasons he chose Egypt instead. In a way, this decision suited Horowitz, for he allegedly confided to a friend that if anyone could have displaced him from his dais, it would have been Ignace Tiegerman. Horowitz Later repeated his confession to AUC's Professor Scanlon when the latter was on a visit to New York.

Tiegerman arrived in Cairo in 1931, just as Conservatoire M. (Joseph) Berggrun of Chawarby Street was getting ready to celebrate its 10th anniversary. Three years would pass before the immaculately dressed Pole with the nasal voice took over the conservatoire changing its name from Berggrun to Conservatoire Tiegerman. Shortly thereafter he relocated it to larger premises at No. 5 Champollion Street. Accompanying Monsieur to the new locale was violinist Adolphe Menaszes. Like Tiegerman, he was an immigrant Pole (from Lwow) who had studied under Karl Flesch and other great masters. Menaszes had done the standard European tour before joining the Berggrun in Egypt. But unlike the Tiegerman who remained celibate, Menaszes was married to Sela Menaszes, a pianist in her own right who became an active member of Conservatoire Tiegerman

Conservatoire Tiegerman, where French was the lingua franca, outdid its contemporaries one by one. By the 1960s the Academie de Musique on Rue al-Mahdi No. 9 run by Joseph Richter; the Academia Pianistica Scarlatti at No.1, Midan Soliman Pasha run by V. Carro; the Music Institute of E. Tcherniavsky on Midan Kantaret al-Dikka No. 4; and Joseph Szulc (a Pole formerly with Berggrun) on Abdel-Hamid Bey Said Street No. 7, had all folded up. Only Tiegerman's remained open for business.

Because he suffered from asthma Tiegerman was obliged to live in Helwan, a dry resort 18 kilometers south of Cairo which meant commuting daily into the city by train. In an effort to shorten the distance, Monsieur relocated to the green suburb of Maadi, a move which ended in a hasty retreat. The suburb's abundant flora had a disastrous effect on the diminutive Pole. For a very short while Tiegerman moved to Rue Abbas in Heliopolis, north west of Cairo.

When Rommel started his WW2 offensive towards Alamein, Tiegerman, like many other alarmed members of his faith, took refuge in the Sudan where he reportedly gave the first ever piano concert in Khartoum. Upon his return to Cairo in 1943, and with the encouragement of American pianist Muriel, wife of AUC's dean Worth Howard with whom a cordial relationship had developed in the Sudan, Tiegerman became an active participant in Lady Thomas Russell Pasha's 'Music For All' benefits giving several charity performances. Otherwise, Tiegerman's public appearances were few and far between. Yet whenever he performed, it was always to a full house. Such was the case when he played at Cairo's Royal Opera House in December 1949 on the occasion of Chopin's centenary.

One reason why Tiegerman was short on public performances was that he would only perform when he was paid the fee a pianist of his stature deserved. On one of the rare occasions where Monsieur shared confidences with a student, he exclaimed that he would only play with the Egyptian Symphony Orchestra if he was treated as was treated Alfred Cortot and Wilhelm Kempff. And since his fee could only be met every two or three years, he would therefore play every two or three years as did other famous visiting pianists.

On the other hand, Tiegerman charged his students one pound per lesson, a hefty sum in the 1950s.

One of Tiegerman's last broadcast performances was on May 13, 1960, at the Cairo Opera House where he played Chopin's 1st Concerto in mi minor op.11 for piano and orchestra. On the same program was Dvorak's 8th symphony and Debussy's 'Prelude a l'Apres-midi d'un Faune' performed by the Cairo Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Gika Zdravkovitch with Johannes Zneker, leader. (There were two performances on this day, the first at 11:15 mainly for students, and the second at 21:15, for the paying public.)

Tiegerman who did not like being called 'maestro' claimed he was just trying to be 'a good piano player and that's all.' He hardly ever played for his students, recalls Papastephanou, "but I had the great privilege of having him play the last movement of the Egyptian Concerto by Saint Saens, the end of the Mephisto Waltz (Liszt), Chopin Etudes (Op. 25, No.6), and many other pieces I was studying at the time."

Summing up his thoughts on his 'Tiegerman experience,' a former student remembers how, when he resumed piano in the United States in the 1960s under the guidance of Leon Fleisher, he felt like Tiegerman had never ceased to look over his shoulder, giving him advice: 'un peu moin fortissimo..., lentement, lentement.'

"Although Fleisher was an excellent teacher, Tiegerman was unequaled" says Papastephanou. "Whereas the other teachers suggested exercises of all kinds (Fleisher recommended the 51 Brahms exercises for example), Tiegerman never required the practice of scales or exercises. Instead he went straight to the meat and taught us how to produce the sound and play the piece in the most intelligent, beautiful way, bringing everything offered in the score of light."

Ignace Tiegerman spent his final days at Zamalek's Anglo-American (Zamalek) and the Greek hospital in Abassia. He died from prostate cancer on May 30, 1968 surrounded by his former students and admirers -- Laila Orabi, Prince Hassan Hassan, Aicha Hamdi among them. The secular virtuoso, to whom are indebted several generations of Egyptian and international musicians, was buried in the Jewish cemetery of Bassatine outside Cairo. Two notable absentees at his modest funeral were pianist Marcelle Matta who was getting married on the same day, and Henri Barda, who since 1957 was a resident of France.

If anyone is meant to carry Tiegerman's legacy into the next millennium, it is undoubtedly Barda, winner of the 1990 Grand Prix du Disque Frederic Chopin in Warsaw for his recordings of the three Chopin's sonatas. It was the leading French musical monthly Le Monde de la Musique which named Barda the best Chopin interpreter of his generation. Meanwhile, Le Monde's senior music critic, Alain Lompech, described him admiringly as "Le cas Barda."

Barda vividly recalls his final meeting with Monsieur in the early 1960s in Kitzbuhel, Austria. In Monsieur's tiny chalet, former star student and veteran professor performed for each other. Sadly, Tiegerman died without ever hearing Barda in live concert.

Another Tiegerman disciple, Columbia University's Edward Wadie Said, would write about the legend of Tiegerman evoking, eulogizing and at times analysing the 'remarkable' Pole.

With no known heirs in Egypt, Tiegerman's prized possessions were given new but appropriate homes in Cairo. While one of Monsieur's Steinway pianos ended up with striving Egyptian pianist Moushira Issa part of his book collection ended up with Ramzi Yassa, Egypt's leading contemporary pianist. Years later, Issa would put together a scanty brief on Monsieur as part of her thesis at an Austrian University.

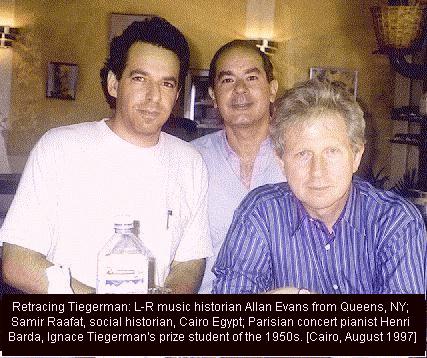

This summer, New York music historian Allan Evans arrived in Cairo looking for information and recordings by Ignace Tiegerman. With the help of Henri Barda, Stephen Papastephanou, Prince Hassan Hassan, Selim Sednaoui and other Tieger-ites, a sketchy biography was pieced together. A world hunt for Tiegerman's music produced scratchy but rare recordings, most of them from live concerts. With the assistance of modern technology and state of the art computers, these will be digitally transferred onto CDs. Soon, musicologists around the world will have the opportunity to appreciate the man who allegedly would have surpassed Horowitz.

|

FROM THE NEW YORK TIMES ARTS & LIVING SECTION April 18, 1999 Old Records In High Tech and Low

News of Rachmaninoff's return from the grave by way of technology appeared in this space not long ago and has generated considerable response. I now have in hand CDs of Granados playing Granados and Debussy playing Debussy, both thanks to the same kind of updated player-piano technology that made the great Russian pianist and composer rematerialize before our ears.

Nimbus Records has sent along Ignaz Friedman playing Liszt and Chopin in Aeolian's Duo-Art process in the early 1920s. Names like Aeolian, Welte-Mignon and Ampico are becoming as familiar to music historians as Forkel, Kochel and C.P.E. Bach.

Some wisdom has it that these are our new intermediaries to long-dead traditions. Master rolls have been cleaned up, the mechanical has given way to the computerized, and shiny new pianos have been tuned up to receive and disburse the "real thing."

Along with CDs of these reproducing pianos (for new technology does deserve a more dignified name) have come examples of traditional recording archeology: Emil von Sauer recorded live in Amsterdam and Vienna, and most intriguingly, Ignace Tiegerman recorded in Cairo, often from his own parlor. Both are on the Arbiter label of Allan Evans, the organizer of Lincoln Center's recent series "Great Pianists of the 20th Century on Film."

Anyone who gets anywhere near a record store or catalog knows that "historic" releases are coming from every direction. Legitimate enterprises like Nimbus' "Grand Piano" series and Philips' giant new survey of the century's best pianists compete with pirate tapes of murky legitimacy.

Marston, an up-and-up little company from Pennsylvania, has given us a series of valuable opera-singer recordings of Tito Schipa and his long-dead colleagues.

Our appetite for the long-ago is growing, and two methods vie for our custom. One uses technology to bring old performances into the present. Musician-engineers like John Farmer in London and Kenneth Caswell in Austin, Texas, make Debussy sound with all the nuance and resonance of those who interpret him on records today.

The second method comes to us from a distance: scratchy, distorted, depleted, often translated from one-sided, 78-rpm shellac or even a cylinder. The sound incorporates the faraway as a part of the listening experience.

Recording quality becomes a metaphor for the passage of time. Affixed in our minds is the message that years of change stand between the original experience and the reproduced one, and that we should not forget it.

I am often in awe of the reproducing-piano experience, but oddly, my heart lies more with the cracks, pops and top-heavy sound of its competitor. As in sex, it is not the open leer and full disclosure that lodge the heart in the throat; it is the veiled, the suggested, the withheld, even the forbidden. Prolong the expectation, set the goal just out of reach, and increase the attraction.

The principal players in my little collection of antiques are Enrique Granados, representing the reproducing piano, and Tiegerman, spokesman for the old spinning disk. Hearing the grace and command of Granados so shinily presented on Caswell's private label helps one understand why this music can be both so erotic and so dense with complication. Granados could manage both elements and does.

Granados was a Catalan and died at sea in 1916, trying to rescue his wife after their ship had been torpedoed. By way of Welte-Mignon rolls made in 1912, we hear the wonderfully dark and overgrown quality of four excerpts from "Goyescas," a work famous enough in the early years of this century that the composer was induced to turn it into a mini-opera. We know this music mainly because of Alicia de Larrocha, one of the few pianists of similar culture and the requisite technique.

The two Tiegerman CDs have even more of the romance of history. The Arbiter release is subtitled "The Lost Legend of Cairo: Radio and Private Recordings," and offers, sometimes in scraps, Brahms and Saint-Saens concertos and the Franck "Symphonic Variations," taken from Egyptian radio.

There are tapes of Chopin from homes of students and Tiegerman's studio. Especially, there are stunning, elegant performances of Brahms' B minor Capriccio (Op. 76, No. 2) and B flat minor Intermezzo (Op. 117, No. 2). |

|

|

Saturday, May 01, 2004 11:51 PM |

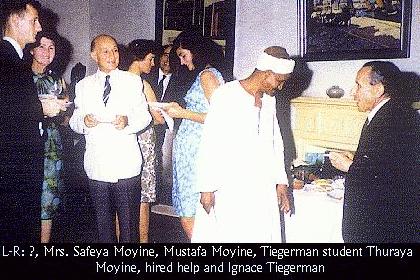

pictures of Tiegerman courtesy of Allan Evans in New York

|

|

|

|